Book Review: “Who Owns This Sentence?: A History of Copyrights and Wrongs”

By David Mehegan

This book is a fiery manifesto that charges that copyright law today is an outrageously unjust scheme that does nothing for 99 percent of authors, other creative people, and their fans, while it locks up a commodity that fills the coffers of large corporations.

Who Owns This Sentence?: A History of Copyrights and Wrongs by David Bellos and Alexandre Montagu. W.W. Norton. Cloth. 384 pp. $28.99

Most writers suppose they understand copyright. You write a book, put “copyright ©” before your name on the page that follows the title page, and add the phrase “all rights reserved.” Your ownership of the work is assured for … some great number of years, after which your copyright expires and the work enters the public domain. That is, if you and your literary heirs pay attention and sue anyone during the period of copyright who dares to republish your writing without first seeking permission.

This much is true, but most of us have not considered the reason for this convention, whether it makes sense, and whom it really benefits. Princeton literature professor David Bellos and British copyright lawyer Alexandre Montagu seek to answer those questions with this detailed history. They are up to more than that, however. This book is a fiery manifesto that copyright law today is an outrageously unjust scheme that does nothing for 99 percent of authors, other creative people, and their fans, while it locks up a commodity that fills the coffers of large corporations.

Their signature example is SONY Music Group’s 2021 purchase of rights to the songs of Bruce Springsteen for a reported $550 million. With that deal, SONY can charge handsome fees, mounting over the next (probably) century and a half into the billions of dollars, for every use of the New Jersey kid’s music: recordings, sheet music, translations, old broadcasts, publicity imagery. “Mozart was not so lucky!” they sneer, “Nor Ray Charles for that matter.”

As a young editor at Houghton Mifflin in 1972, I learned the basics of copyright law. A written work could be copyrighted for a term of 28 years, then renewed by the author or his estate for 28 more, for a total of 56 years. Any author whose book I worked on had to seek and then receive in writing permission from the rights-holder for even short bits of poetry and direct prose quotations that exceeded 250 words. The old “fair use” doctrine — more tradition than clear law — provided that an author could quote a copyrighted work without permission up to 500 words. But dear old HMCo (now Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), being a conservative New England publisher, wanted to be on the safe side and lowered that ceiling to 250.

The author was obliged to find and write to the rights-holder. Usually, a publisher’s permissions department would soon send a contract letter requiring specification of the material to be used, naming the fee to be paid (and remitted to the quoted author), and prescribing the exact words of permission to be printed on the acknowledgments page of the new work (“Sentences from John Smith reprinted by kind permission of…” etc). If you could not find the rights-holder of some obscure novel published in 1949, you couldn’t use the material and risk somebody coming out of the woodwork and suing you and the publisher for copyright infringement. Permissions contracts were kept on file and the fees were charged to the new author’s advance or royalty, if any.

This gentlemanly old system seems quaint nowadays, especially since the 1976 revision of the US copyright law. Under the pressure of giant media companies like Disney and with the help of lobbyists who wrote the law, when you copyright a work today (no © is necessary, by the way), you own the rights for your lifetime, even if you live to be 100, and your heirs (or a rights-buyer like SONY) control them for 70 years beyond that. “Work for hire,” such as stories written by newspaper reporters, is protected for 120 years after creation or 95 years after publication, whichever is shorter. Besides writing, copyrightable material includes films and paintings, photographs or other images, plays, video games, dances, computer code, cartoon characters like Mickey Mouse, and the lyrics and recorded performances of the Beatles and Bruce Springsteen. While patents on inventions still expire after 20 years, copyright goes on far beyond the lifespan of the creators.

Article I, Section 8 of the US Constitution (modeled on the British Statute of Anne of 1710) provides that Congress shall have power “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” In 1790 the first US copyright act was modeled on Section 8, with the added specification that copyright was for 14 years, renewable once for 14 more. The idea was to encourage writers and inventors to accept the risks of their works on the assurance that they could, “for limited times,” retain control and financial benefit.

Alexandre Montagu. Photo: Parivash Moazed

But Bellos and Montagu argue that the protection of benefit is a myth: “People write original works of literature for all manner of reasons,” they write, “self-expression, score-settling, inner compulsion, sheer pleasure, to acquire prestige. Those few among them who put pen to paper to earn a crust are typically among the least original and so the least in control of their rights…. As Condorcet foresaw in the eighteenth century, literary property vested in authors essentially rewards the producers of trash.”

So much for the dignity of authorship. They are surely correct that copyright does not guarantee wealth to authors, since the vast majority (aside from the Danielle Steels, J.K. Rowlings, and John Grishams) sell few books and earn little on those they do sell. Furthermore, pace Dr. Johnson, it’s not true that “no man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money.” If that were true there would be no Canterbury Tales, no Shakespeare, no Walden, no first novels, and assuredly no poets.

Therefore, the idea that copyright is essential to encourage authorship is nonsense. Or so say Bellos and Montagu with a characteristic tone that no man but a blockhead could fail to see it their way: “Arguments for the incentive effect of intellectual property protection are confined to what James Boyle calls an ‘evidence-free zone.’ We would add: and to a logic-free world.” One gets the strong sense that they are most sympathetic to those who want to use copyrighted works but resent having to pay for it.

It’s hard to argue with Bellos and Montagu that copyright law has grown into a many-headed, nearly immortal monster that too often protects only the wealth of those who buy or inherit rights. It has been corporations such as Disney which have pushed to extend and widen protection by law. The Springsteen case is one of many. Just this month, for example, the doddering rockers in the band Kiss sold their song catalog and brand name to a Swedish media company, reportedly for $300 million.

Whose creativity does that encourage? All right — probably nobody. And yet, we might ask, who gets hurt by it? There aren’t that many enormously wealthy Springsteens and Kisses in the creative universe. If you want to cover a Springsteen song, do you care whether you pay Bruce or pay SONY? (And will anyone pay a dime to do so a hundred years from now?) The Internet has perhaps unrealistically encouraged the expectation that everything should be free.

Who Owns This Sentence? is a comprehensive history, going back to ancient Greece, and useful for that. We learn about the roots of copyright in the Statute of Anne, the 1886 European Berne Convention, which laid the foundation for modern copyright law, and a long array of historic laws and court suits and rulings, in Europe and North America, leading up to the US 1976 revision. All that is good to know, but the narrative is so chopped up that developments are sometimes hard to follow, with 43 chapters, many of them only a few pages long, breaking up 330 pages of text. And the history is heavily overlaid with tendentious argument. “Berne no longer has much to do with the rights of genius,” Bellos and Montagu write. “The principal function of its successor treaties and organizations today is to regulate a roaring international engine of corporate rent.”

Whatever the merits of their strong point of view, Bellos and Montagu are excessively cavalier in their derision of the legal and moral world of copyright. They assume it really is all about money (“corporate rent”) for the haves and devil take the have-nots. They denounce the laws we have now. But tellingly, given all their snarking and sneering, they offer no particular reforms — not even how long the term of copyright should be. Instead they end with a weak call for “a broad debate about … changes in the law.”

Reform of copyright law to fairly rebalance the rights of owners with those of users of intellectual property probably is advisable. Whatever that might entail, however, I believe that virtually every writer thinks that her copyright matters, even if she never makes a dime on it.

David Bellos. Photo: Princeton University

When I was book editor of the Globe in the ’90s, the New York Times — then owner of the Globe — informed all the freelance reviewers that they would have to sign an agreement henceforth turning over copyright of their reviews to the Globe. Most of them did, not without grumbling. But one excellent reviewer — well known to the Editor of the Arts Fuse – refused to sign and never wrote another review for the Globe. I remember his saying to me, “The only thing a freelance writer has is his copyright.” Did he say that because copyright was the only thing that enabled him to write? Certainly not. Did he hope someday to sell the rights to his collected reviews for $300 million? He would be lucky to sell them for $3,000. No, he was standing up for his pride of ownership in original work. He felt that an artist should be able to say, “This is my creation, I get the credit for it and should get my rightful share of the value it generates — however minute.” I hated to lose his reviews but admired his gumption.

This kind of ownership is under attack, but not by the SONYs of the world. A greater threat is posed by digital behemoths like Google, OpenAI, and Meta, who, to fuel their AI ambitions, are eager to vacuum up creative products from the Internet, even those of Grub Street strugglers. The New York Times reported last week, “At Meta, which owns Facebook and Instagram, managers, lawyers, and engineers … conferred on gathering copyrighted data from across the Internet, even if that meant facing lawsuits. Negotiating licenses with publishers, artists, musicians, and the news industry would take too long, they said.”[1] How can the humble artist guard against this kind of larceny? Bellos and Montagu don’t mention it.

Who Owns This Sentence? is “copyright ©”, of course, by Bellos and Montagu. While they might not think it worth the line of ink that expresses it, they did not volunteer to yield copyright to W.W. Norton. Ironically, they heap praise on novelist Jonathan Lethem for “The Ecstasy of Influence,” his “marvelous” 2007 essay in Harper’s Magazine “consisting mainly of sentences copied out from elsewhere.” They quote him approvingly: “The name of the game is Give All. You, reader, are welcome to my stories. They were never mine in the first place, but I gave them to you. If you have the inclination to pick them up, take them with my blessing.”

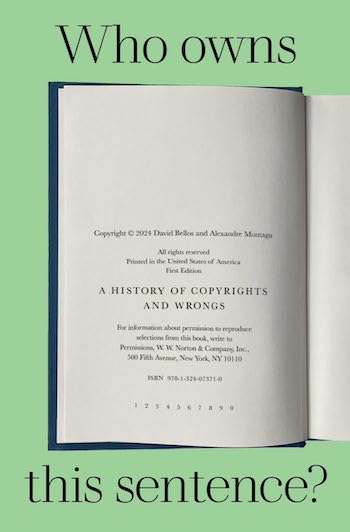

In a bit of designer’s cleverness, the dust jacket of Who Owns This Sentence? reproduces almost word for word the book’s actual copyright page. Almost — but not quite. It omits a sentence that someone didn’t want to call attention to: “Extract on p. 31 from Jonathan Lethem, “The Ecstasy of Influence,” copyright © 2007 Harper’s Magazine. All rights reserved. Reproduced from the February issue by special permission.” So Lethem didn’t copyright the “marvelous essay,” but Harper’s did. Though “fair use” is still protected under Section 107 of the US Copyright Act — and Bellos and Montagu’s short quotation of Lethem would certainly have been covered by it — it seems Norton didn’t want to take a chance that Harper’s would haul them all into court. Perhaps Lethem would have been a witness for the defense.

David Mehegan can be reached at djmehegan@comcast.net.

[1] Cade Metz, Cecilia Kang, Sheera Frenkel, Stuart A. Thompson, and Nico Grant, “How Tech Giants Cut Corners to Harvest Data for AI,” April 8, Section A, Page 1.

Tagged: A History of Copyrights and Wrongs, Alexandre Montagu, copyright