Author Interview: Historian Steven Hahn on “Illiberal America”

By Blake Maddux

“The hardest part of the book for me to write was the conclusion. It’s a very dark book. I didn’t want to write a dark conclusion, but I also didn’t want to be Pollyannaish about it.”

People who — like me — check all (or at least several) of the privilege boxes often post hyperbolic boilerplate on social media about how the United States/America is the greatest nation of all time.

When I see this, I ask myself if any of these individuals would be willing to “quantum leap” into someone demographically different from them in a different era of American history or, for that matter, the present.

Would they be willing to undergo the de jure and de facto discrimination, inferior treatment, and outright horrors suffered by Black people, women, Native peoples, Catholics, Mormons, Jews, immigrants, the indigent, the illiterate, and the currently or formerly incarcerated?

Having done so, do they expect that they would return to their present selves equally convinced of America’s nonpareil greatness?

The fact — and I think that it can be called that — is that those exalted for crafting the Declaration of Independence and framing the US Constitution were not particularly keen on affording rights, privileges, immunities, etc. to those who differed from them in race, gender, national origin, religion, net worth, and level of education. (And I presume that the same would apply to sexuality and gender had they been issues at the time.)

Of course, the subsequent generations of Americans have been slow at best to recognize the justified demands of those long relegated to second-class (again, at best) citizenship.

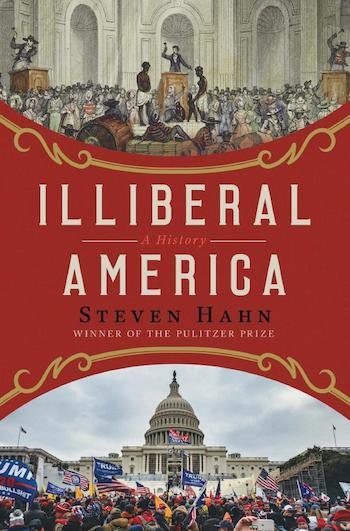

New York University professor and 2004 Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Steven Hahn takes a deep dive into this unfortunate tradition in his new book, Illiberal America: A History.

Not only does Hahn proclaim, “Illiberalism’s history is America’s history,” he observes that it is at least as healthy in the age of Donald Trump as it has ever been.

“To find an analogous era of illiberal darkness,” he writes, “we would have to go back at least to the McCarthyite repression of the 1950s or, more likely, to the government-endorsed fascist pulses of the 1920s.”

Professor Hahn spoke to me by phone in advance of his visit to Harvard Book Store, where he will discuss Illiberal America with author and Harvard Kennedy School professor Alexander Keyssar on April 2.

Arts Fuse: In what ways did you find yourself venturing outside of your comfort zone in writing this book?

Historian Steven Hahn. Photo: Kate McCall

Steven Hahn: It’s hard to describe comfort zones as historians, because we sort of end up roaming all over the place in our teaching.

As it turned out, I wrote a US history textbook (Forging America, volumes one and two) before I started on this. I had spent so much time reading all over the place in order to complete this textbook. Much of my writing and teaching had been focused on the 19th century, and Illiberal America required me to move both backward and forward. It goes way back into the 17th century and then finishes up in the very near present.

In some ways, when you wade into areas that you’re unfamiliar with, there’s apprehension and excitement. I learned a lot and felt challenged. There are areas that I write about in this book that I don’t know a lot about, but ended up making strong arguments. I’ve tried to be very respectful of other scholars and to lay out an argument about illiberalism that is not meant to be tendentious.

AF: Is “illiberalism” a word that frequently appears in the historical literature?

SH: It is a term of recent vintage. I think one of the first people to offer it up was Fareed Zakaria, who had an influential essay in the 1990s. But he wasn’t talking about the United States.

The challenge for me was how to take a concept that is of recent vintage and use it to talk about a historically deep phenomenon. I was basically looking for a concept that was capacious enough that it could encompass a variety of phenomena, and flexible enough that you could see change over time.

Part of what I tried to do is show how aspects of illiberalism manifest themselves differently but nonetheless substantially.

AF: How did you narrow down what to focus on?

SH: I tried to pick out moments in the past that we tend to associate with the development of liberalism and interrogate them in ways that raises questions and shows the illiberal currents that run through them.

In a lot of ways, American democracy was highly illiberal because of its exclusionary aspects. And now we’re watching a process going on in the states — reinforced by the Supreme Court’s gutting of the Voting Rights Act — that’s a kind of return to the period of the late 19th century/early 20th century, when disenfranchisement became a project of states and the national government.

AF: What have been some of the frequent or even inescapable features of illiberalism over the centuries?

AF: What have been some of the frequent or even inescapable features of illiberalism over the centuries?

SH: Illiberalism is composed of a number of interconnected ways of thinking and acting. It would include the embrace of certain kinds of assigned hierarchies, whether they’re of gender, of race, or of nationality. It’s a rejection of the idea of equality. It would involve a kind of embrace of cultural homogeneity.

I think about illiberalism in terms of what I would call limited rights-bearing. People don’t necessarily believe in rights for other people. Illiberalism usually involves the marking of internal and external enemies. In fact, one of the things that I’ve been struck by is how the will of the community sometimes overrides the rule of law. Community is a vague concept, and people invoke it even though they really can’t define it, but they think they know what it means.

AF: To what extent and in what ways does Donald Trump embody illiberalism?

SH: People like Trump are able to tap into ideas, practices, and dispositions that have always been close to the surface. One of the things that made Trump popular was that he spoke a language that validated people’s thoughts and fears.

His political ideas, insofar as there’s any coherence to them over time, have always traded in racism and hyper-American nationalism. His political ability is to tap into people’s fears, including the Central Park Five and the Obama birther stuff, which uses an old Reconstruction trope about the illegitimacy of Black people’s participation in politics. It gained unbelievable traction, which was a warning sign. He recognizes that his future is tied up with the extremism of the Republican party, which is clearly one of the faces and drivers of extreme illiberalism.

AF: Given the United States’s deep and ongoing history of illiberalism, what are your thoughts on the present political climate?

SH: The hardest part of the book for me to write was the conclusion. It’s a very dark book. I didn’t want to write a dark conclusion, but I also didn’t want to be Pollyannaish about it.

But it’s pretty clear that we’re living in a very illiberal moment globally. In some ways it’s like the late 19th/early 20th century that produced fascism, although I don’t like throwing around that term. We’re looking at a moment where illiberal ideas and orientations have gotten credibility that they haven’t in a long time. To the point that people are willing to embrace them publicly. And the Republican party has basically gone over that way. There’s no faking around, there’s no saying, “no, that’s not what we mean.” It’s pretty direct expression of what they want to do and how they look at the world. So I think that’s really what the dangers are at the moment.

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who regularly contributes to the Arts Fuse, Somerville Times, and Beverly Citizen. He has also written for DigBoston, the ARTery, Lynn Happens, the Providence Journal, The Onion’s A.V. Club, and the Columbus Dispatch. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife and six-year-old twins — Elliot Samuel and Xander Jackson — in Salem, MA.

were you raised in Illinois?