Book Review: “Spirit of the Century” — The Inspiring History of the Blind Boys of Alabama

By Noah Schaffer

Spirit of the Century is a riveting celebration of the Blind Boys of Alabama’s glorious and often unpredictable musical journey.

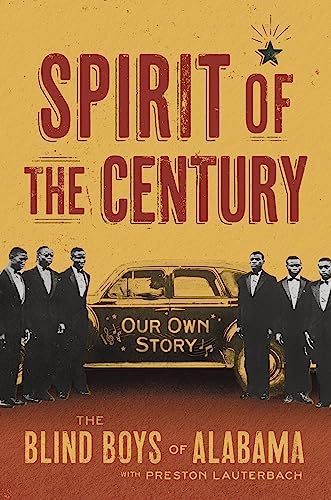

Spirit of the Century by the Blind Boys of Alabama with Preston Lauterbach. Hachette, $30, 320 pages.

While there’s no disputing that neither rock nor soul would exist had it not been for quartet-style gospel, the story of the sacred singers that spent their lives on the gospel highway remains under documented. Only a handful of important groups have been the subject of their own books. Those efforts have been supplemented by the documentary How They Got Over and Alan Light’s indispensable study Woke Me Up This Morning, which shows how the quartet scene has remained vibrant.

Now comes another welcome addition to the canon: Spirit of the Century, the story of the Blind Boys of Alabama, the group who formed in 1939 at the Alabama School for the Negro Deaf and Blind, an abusive institution where students were given insufficient meals and even more meager career options, like broom making. As anyone who has turned on NPR, looked up the Grammy nominations, or glanced at a performing arts center concert calendar likely knows, the group has been the toast of the roots music world ever since they appeared on Broadway in The Gospel at Colonus in the mid-’80s.

Spirit of the Century is officially credited to the group itself and carries the copyright “The Blind Boys of Alabama, LLC.” Nothing is provided regarding which of the current or former members should be credited. The name of co-author Preston Lauterbach, who has written several excellent tomes examining Black Southern culture, may be in the small type on the cover, but the story is essentially told in his voice.

As he has done before, Lauterbach wonderfully combines historical research with storytelling. Too many music histories dryly rely on discographies for their narratives, but Lauterbach realizes that most of the quartet’s life was lived on the road. And over the decades the group generated manifold musical glories, particularly when the singular Clarence Fountain sang as its lead. The group wrecked the houses of worship and school auditoriums it appeared in, and made spine-tingling records for legendary labels such as Specialty. Even more impressive: the tales of how the members never let their visual handicap hinder their ability to take care of the group’s business.

Of course, there was little glamor in being a blind group traveling through Jim Crow America to sing for pittances, when the promoters bothered to pay them at all. And it’s no secret that not every gospel singer lives the spiritual life that they sing about. Lauterbach details the womanizing and as well as the confusing circumstances surrounding the gun play that took the life of the Blind Boy’s first lead singer.

Lauterbach also tells how for decades the story of the Blind Boys of Alabama was intertwined with the Blind Boys of Mississippi, a group that was arguably even more important in the development of quartet gospel, especially when Archie Brownlee was its lead singer. Amazingly, the Mississippi group also had an apparently trans male member — Willmer “Little Axe” Broadnax.” The two bands often “battled” during programs, and over the course of their histories multiple singers were members of both groups, with even Fountain briefly defecting to the Mississippi group. Fountain was an intriguingly complex character. His vocal power was matched by his biting wit: “All these places look the same to me,” he cracked during a mid-’90s appearance in Cambridge. When dialysis treatments took him off the road in 2007 Fountain bitterly complained in interviews about his treatment by the group, which by then had secured professional management to oversee its busy international touring schedule. His grievances are addressed in Spirit of the Century, as are happier revelations as well, including that they had been resolved by the time Fountain died in 2018 (although his will kept his children from enjoying either his royalties or his multiple Grammy trophies).

The Blind Boys of Alabama. Photo: Jim Herrington

Another Blind Boy who sang with both groups, Jimmy Carter, is one of the other central characters in the story. Blind Boys of Alabama concerts in recent decades climaxed when Carter would jump off the stage, running up and down the aisles. But gospel history buffs have been baffled about Carter’s history with the group; he was billed as an original member, yet he is absent from the quartet’s great ’50s and ’60s recordings and TV clips. The explanation: Carter was a young student at the Alabama School who sang with the then-teenage group, but his parents wouldn’t let him leave to go on the road once the troupe turned professional. It’s not just audiences that love the “Jimster” – his ability to connect with younger artists has been a key part of the group’s recorded collaborations with everyone from Lou Reed to the Oak Ridge Boys. Rock and country star cameos have played a crucial role in the group’s successful crossover output.

On the one hand, Spirit of the Century is a riveting celebration of the Blind Boys’ glorious and often unpredictable history. But, for a book about sacred singers, it is a bit light when it comes to examining the personal faiths of the members who have devoted their lives to a musical ministry. Also, ironically, the volume comes out at a time when the group’s future is murky. Last fall the Blind Boys of Alabama released one of its best albums in years, Echoes of the South. But two of the singers featured on it, Ben Moore and major gospel legend Paul Beasley, both passed away before the recording came out. Carter, now 92, has finally retired from the road. That means only two of the five faces on the current promotional photos provided to venues, such as the Center for the Arts at the Armory in Somerville (where the group will be appearing on Thursday night) will be performing: Ricky McKinnie, who started as a drummer before becoming one of the front line singers about a decade ago, and sighted guitarist and longtime music director Joey Williams.

In Spirit of the Century, the group’s manager Charles Driebe calls the Blind Boys of Alabama a “franchise” that will continue regardless of its specific members. Outrageously, the Blind Boys’ website doesn’t even bother to list the names of new members J.W. Smith or Sterling Glass. For now, they’re tasked with singing the songs that their predecessors made concert staples, such as Norman Greenbaum’s “Spirit in the Sky,” an arrangement of “Amazing Grace” that uses the melody of “House of the Rising Sun,” and a version of Tom Waits’ “Down in the Hole,” which was the theme song for The Wire. There is certainly enough commercial demand for the Blind Boys to go on regardless of who is singing. Still, it remains to be seen if this inspiring institution will develop artistically.

The Blind Boys of Alabama appear with opener Tim Hall at the Center for the Arts at the Armory on March 14 at 8 p.m.

Noah Schaffer is a Boston-based journalist and the co-author of gospel singer Spencer Taylor Jr.’s autobiography A General Becomes a Legend. He also is a correspondent for the Boston Globe, and spent two decades as a reporter and editor at Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly and Worcester Magazine. He has produced a trio of documentaries for public radio’s Afropop Worldwide, and was the researcher and liner notes writer for Take Us Home – Boston Roots Reggae from 1979 to 1988. He is a two-time Boston Music Award nominee in the music journalism category. In 2022 he co-produced and wrote the liner notes for The Skippy White Story: Boston Soul 1961-1967, which was named one of the top boxed sets of the year by the New York Times.

This is an excellent review, Noah. I enjoyed the breadth and depth of your assessment of the book, and learned a lot I hadn’t known about The Blind Boys.

BTW. I was there for The Gospel at Colonus when they made their entry into the broader music world.

Thank you for the memories

Anne Serafin