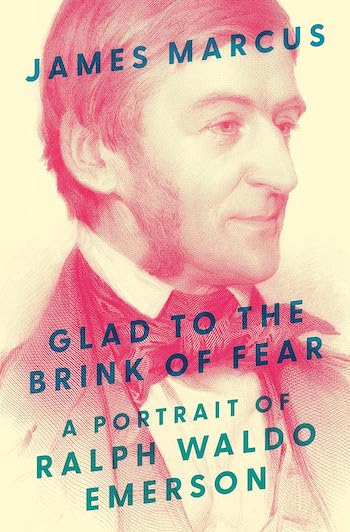

Book Review: “Glad to the Brink of Fear: A Portrait of Ralph Waldo Emerson” — Generous and Eloquent

By Peter Behrens

This arch-New Englander, descendant of Puritans, is also “the American who resists branding, who will not be commodified.”

Glad to the Brink of Fear: A Portrait of Ralph Waldo Emerson by James Marcus. Princeton University Press Princeton NJ and Oxford, 328 pp., $29.95.

Who was he? Who is he? Ralph Waldo Emerson occupies some acreage in the American conscience but where exactly can we situate him? Philosopher? Political activist? Performer, huckster, man-of-letters? In Glad to the Brink of Fear, James Marcus’ fresh and insightful portrait, Emerson is seen in most of those roles, with the honorable exception of huckster. He never was that, though he was born in and always fascinated by a country where, in the nineteenth century as in the twenty-first, powerful salesmanship — of religion, amongst other articles — was honored above almost everything.

Who was he? Who is he? Ralph Waldo Emerson occupies some acreage in the American conscience but where exactly can we situate him? Philosopher? Political activist? Performer, huckster, man-of-letters? In Glad to the Brink of Fear, James Marcus’ fresh and insightful portrait, Emerson is seen in most of those roles, with the honorable exception of huckster. He never was that, though he was born in and always fascinated by a country where, in the nineteenth century as in the twenty-first, powerful salesmanship — of religion, amongst other articles — was honored above almost everything.

If Emerson was anything he was honest, sometimes painfully so. (It made him “nervous and wretched” to read much of his friend Henry Thoreau’s prose.) He was certainly far more interested in ideas — and in the idea of having ideas, and what our human tendency to have, hold, and develop ideas suggests about our relationship to God, aka Nature — than he was in merchandising anything, or founding a school of thought, or stoking a fan base.

Emerson is “Waldo” throughout this affectionate study.

The author’s Waldo, in a nutshell: “a mind determined to build an original relationship to the universe.”

The book, in a nutshell: generous and eloquent.

The Waldo we encounter here is “a thinker, writer, travelling lecturer, a political animal surprising himself by the vehemence of delinquent but passionate abolitionism.” And just to make things more difficult for any would-be acolytes, or book reviewers: this arch-New Englander, descendant of Puritans, is also “the American who resists branding, who will not be commodified.”

Does Waldo matter? To us? Well, yes. Why? Two reasons.

The first: after reading enough of him, who needs God? In his own New England nineteenth century, Emerson traveled from the comfortably post-Calvinist Congregationalism of his father, the pastor of Boston’s First Church, through the mildish Unitarianism of Harvard Divinity School, while dropping along the way any notion of Christ’s divinity. After Div School, he stepped onto the career ladder and accepted, with some foreboding, his appointment as pastor to Boston’s ancient and respectable Second Church, which at one time had been presided over by the Puritan divine, Increase Mather, and then by his son Cotton Mather, the pro-vaccine and anti-witch crusader, who, Marcus reminds us, had found time among his pastoral duties to write some 450 books and pamphlets.

Emerson was a legatee of this strain of fierce, small-p protestantism; of its unquenchable appetite for disputing, questioning, and high-stakes arguing over the nature of God, and over our proper relationship to said Deity. Religion to such a people could never be a passive passing-along of lore and liturgy. There was a Bible, certainly, but, read in English, the Book’s fairytale aspects had over the preceding centuries become sort of, well, unavoidable.

The Puritans, the Congregationalists, the Unitarians and Ralph Waldo Emerson are points on a continuum along which a certain strain of Christian belief is gradually stripped of candle-lit, scented mystery as it shape-shifts from the baroque Catholicism of the Renaissance Popes to the Emersonian conviction that even the most plainspoken religion institutions and priesthoods simply aren’t needed anymore, and don’t matter. The self, in fact, is the thing, and the greatest truths are in what Emerson himself called “the foolish details”, or what Marcus calls, delightfully, “the thorny facticity of everyday life.”

In 1832 Waldo had what amounted to a sweet deal, a lifelong gig: a more-or-less tenured pastorship at his Second Church. He gave it up because he could not swallow the institutional belief system and, after several out-there sermons from his own pulpit, it couldn’t swallow him. There was also a very specific reason why he quit the Second Church: he could no longer administer the Lord’s Supper, the ritual by which Christ’s body and blood is symbolically, or literally—there are differences of opinion — consumed by the congregation. Then Emerson doubled down, and offered more heresy from the pulpit just before he was fired: you don’t need God, don’t need the soul, you can still be believer in something that’s much bigger than yourself but is still, in fact, yourself. Your ideas about the world — the fact that you have them — suggests your own divine nature.

Emerson’s Address to the Harvard Divinity School in July 1838 was a homecoming of sorts; he had graduated, ingloriously, from the School twelve years earlier. The Address was also a serious goodbye, and for many years: to the Div School, to Harvard, and to the theology and liturgy of the once-Puritan New England Church as it was represented, in mid-19th century Boston, by Unitarianism. Speaking that afternoon before perhaps no more than half a dozen graduating students, Emerson offered his disbelief in the existence and immortality of the soul, and suggested to his listeners that in such disbelief he had found, and they will find, not despair, but a kind of salvation. He was absolving his listeners — apprentice ministers — of any need for churches and priests to interpret or reveal the individual’s relationship to Nature, elsewhere known as God. Not a good career move.

“By making God another name for nature, or the soul, or some variety of consciousness that is both universal and spiritually bespoke,” Marcus writes, “he gave me a seat at the table.” Marcus suggests that Emerson created space for those, like Marcus, uncomfortable with churches, synagogues, priesthoods, and the faux-wisdoms of various New Ages that have come and gone between Emerson’s time and our own. Not only that, but “his solution to the problem of (our) nihilism is simple and elegant, the product of a Yankee tinkerer, with intangible materials. Seeking the meaning of life turns out to be the meaning of life.”

That Div School Address did not go down well. Andrew Norton, Dean of the HDS, took to the pages of Boston’s Daily Advertiser, urging concerned citizens to “whip the naughty heretic”. The fallout was bitter and hung about for decades.

Emerson’s famous/infamous decision to unbury his young (first) wife one year after her death, open her coffin, and stare at whatever was there: what was that about? Ghoulish Gothicism? Pre-Victorian fetishization of death? Or was it, Marcus suggests, metaphorically in tune with Waldo’s deepest instinct and desire: to look the material world in the face and at the same time to understand it “as a kind of thin skin stretched over a deeper reality.”

Second reason why Waldo matters: his commitment to abolitionism. I suspect we wouldn’t still be reading him, and worrying about what he meant, had he been wrong, or silent, on the most important moral and political issue of his era.

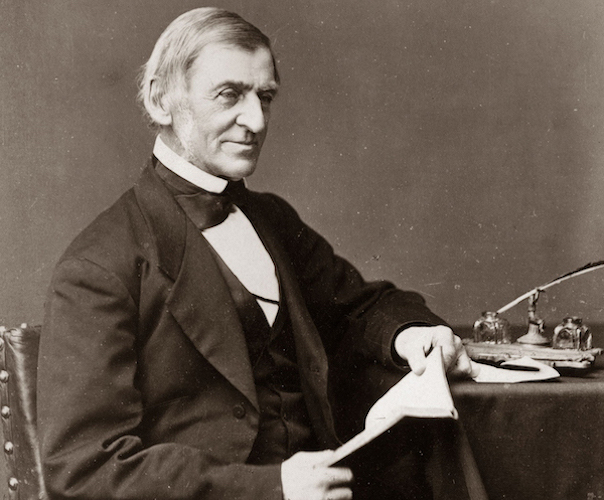

Ralph Waldo Emerson, circa 1870. Photo: Wiki Common

Waldo was, Marcus admits, “a slow learner”, delinquent in his showing-up for the abolitionist cause, which he had initially dismissed as a soapbox for virtue-signaling egomaniacs. He had always hated slavery, but the abolitionist temperament—its passion and its hellfire–was out-of-tune with his own native dispassion. His commitment only took its first step in public on August 1, 1844, when he was invited to speak at the Women’s Abolitionist Society of Concord’s meeting at Concord courthouse.

But the politics of antislavery bored deep into Emerson’s life, and what matters most, Marcus suggests is the intensity and duration of his commitment to abolitionism, which only became stronger and fiercer when the Fugitive Slave Act was passed as part of the Great Compromise of 1850. This legislation transformed all officers of the courts, even in New England, into duty-bound slave-catchers. In May 1851, Emerson received an invitation from the town of Concord to speak out on the hated law. Which invitation he accepted because “The last year has forced us all into politics, and made it a paramount duty to seek what is often a duty to shun”. So, no more dispassion. No more fastidious disclaiming on his own failings as a political animal. In that 1851 talk, Waldo plunges straight into what he viewed as the moral catastrophe of the new statute. It is, he believes, a kind of plague. “We do not breath well. There is infamy in the air” –and from here, there is no turning back. The abolitionist terrorist John Brown is Emerson’s houseguest at Concord. Brown’s daughters find shelter there following their father’s execution in the aftermath of the failed slave insurrection at Harper’s Ferry.

I’ll recommend two other books on RWE that are very much worth reading. Robert Richardson’s Emerson: The Mind on Fire (1996) is the standard biography: a narrative of a life and a mind developing across a sequence of social, intellectual and political settings brilliantly evoked by the author. James Marcus, in his portrait of RWE, is determined to resisted the gravitational pull of chronology — “I will find Waldo where I find him” — but Richardson carefully situates his Emerson in a quick New England stream of history, family and ideas that supply his power and light and his determination to make something new of it all.

Carlos Baker died before completing his Emerson Among the Eccentrics: a Group Portrait (1996) but the not-quite-finished work is an engaging study of intellectual friendship, companionship, and ongoing argument amongst the crew of gifted oddballs — Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, Bronson Alcott, et al — who engaged with Waldo. I am glad I read Richardson first, for chronology and context, and happy to have encountered the Eccentrics with Baker, but I believe I have learned and thought more — about Emerson, and Emerson and us — while reading Marcus’ book than any other.

Peter Behrens’ most recent novel is Carry Me. At PeterBehrensEditorial.com, he helps academics and fiction writers get books and articles across the finish line.

Tagged: Glad to the Brink of Fear: a Portrait of Ralph Waldo Emerson, James-Marcus, Ralph Waldo Emerson

Welcome to the Arts Fuse, Peter, breaking in with this dandy essay. I always find Emerson quite elusive. You pinned him down in a very useful way.

This is a marvelous appreciation of Emerson and a good review of the biographies. Emerson remains crucial to our identity. The best part of this review is its recounting Emerson’s courage. By rejecting the pulpit he risked poverty; he didn’t spring from wealth. Once you read “Nature” you can never forget, “the transparent eyeball.”