Book Review: The Poetic Vision of Larry Eigner — A Gravitational Aesthetic Force Field

By Kevin Gallagher

Jennifer Bartlett’s fine biography is a capstone to a steady solidification of respect for this innovative poet’s art and legacy.

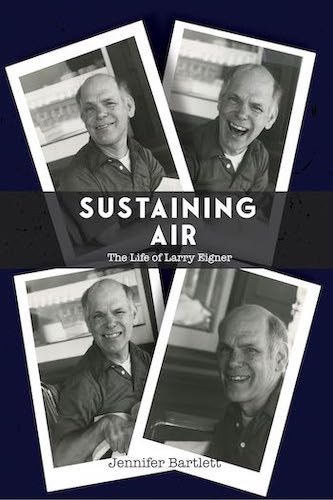

Sustaining Air: The Life of Larry Eigner by Jennifer Bartlett University of Alabama Press. 198 pages.

My father and his two older brothers grew up in Lynn and Swampscott in the 1930s and 1940s. Larry Eigner and his two younger brothers were the same age and lived in the area at the same time. At that point, Swampscott was home to just two thousand households; Swampscott High held a couple of hundred students. I first ‘discovered’ Eigner as a poet in the ’80s. Every time I asked my father if he knew of a ‘Larry Eigner’ on the neighborhood, he would say “No, but the name rings a bell.”

My father and his two older brothers grew up in Lynn and Swampscott in the 1930s and 1940s. Larry Eigner and his two younger brothers were the same age and lived in the area at the same time. At that point, Swampscott was home to just two thousand households; Swampscott High held a couple of hundred students. I first ‘discovered’ Eigner as a poet in the ’80s. Every time I asked my father if he knew of a ‘Larry Eigner’ on the neighborhood, he would say “No, but the name rings a bell.”

It should not be a surprise that he did register the name of a major contemporary poet who, according to poet/critic Charles Bernstein, exerted “a gravitational aesthetic force field unprecedented in American poetry.”

Jennifer Bartlett’s Sustaining Air: The Life of Larry Eigner makes it clear why my father and Eigner never met. The latter led an isolated existence. Physically impaired from cerebral palsy, Eigner didn’t attend public schools, go to the C’s, Sox, or B’s, go to Maddie’s, the library, or the grocery store. Bartlett’s considerations of Eigner’s struggles in her biography are clear-eyed but adroitly empathetic; she considers him firmly and fully as a first-rate poet and in the context of disability studies. (Bartlett is an accomplished poet and shares that she has cerebral palsy herself.)

Eigner’s parents had the financial means and determined love to take advantage of the advances in medical thinking and practice pioneered in Boston at the time. Some with resources would ship their children with disabilities off to eerie places like Willowbrook State School on Staten Island, where it turns out that pupils were abused and experimented upon. Instead, Eigner went to the progressive (for its time) Massachusetts Hospital School (where he published his first chapbook Poems by Lawrence Joel Eigner in 1941). Later he attended Robin Hood’s Barn in Vermont and then took University of Chicago correspondence courses.

Eigner typed his poetry on a Royal typewriter, gifted from his parents, as he sat in the glassed-in front porch on 23 Bates Road in Swampscott. Bartlett draws on Eigner’s papers and interviews to provide a vivid picture of what his home and (intertwined) writing life were like. He lived in a protected world that was overseen by his tireless and committed mother, Bessie. She saw to it that Eigner could read and study. But Bessie also demanded that he sit, be quiet, and ‘not ask foolish questions’ as she entertained guests.

Then, one day in 1949, Eigner heard Cid Corman’s radio show ‘This is Poetry’ on WMEX out of Brandeis University. It changed his life. Corman was reading poems by W.B. Yeats on the program. Eigner immediately wrote to Corman. From that day on Eigner became plugged into a growing network of poets across the country dubbed the ‘Black Mountain Poets.’ The group’s name came from the most famous poetry anthology of the second half of the 20th Century, The New American Poetry, 1945-1960. A number of these poets, most notably Charles Olson and Robert Creeley, taught at the famous Black Mountain college, along with Joseph Albers, Walter Gropius, Jacob Lawrence, Willem de Kooning, Cy Twombly, and many others. Eigner could never physically become part of the Black Mountain experience because of his disabilities.

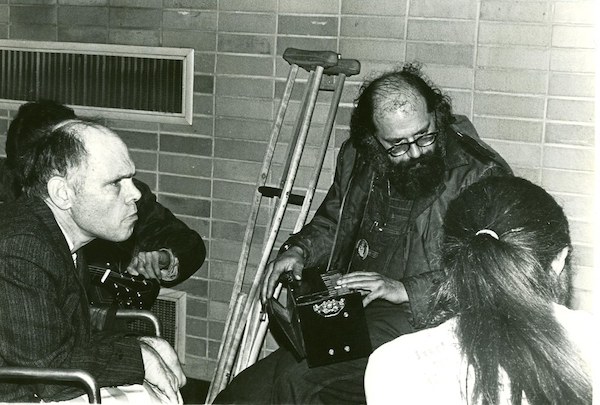

Larry Eigner, Allen Ginsberg, and Peter Orlovsky speaking during the poetry reading at

“A Tribute to Jack Kerouac,” held as part of the Arts Festival at Salem State College in April 1973. It is generally thought to be the first academic symposium on the life and work of Jack Kerouac. Photo: University Archives, Salem State University Archives and Special Collections, Salem, Massachusetts

Interestingly Olson lived much of his life up Route 128 in Gloucester and Creeley in Arlington and Belmont. Eigner’s mother or a friend would drive him to visit Olson; later on, poets would come visit Bates Road in Swampscott. Here, on the front porch, Eiger would greet friends. It is also where, using only his right index finger and thumb, he would write poems or bang out letters to Robert Creeley, Cid Corman, and Margaret Randall.

In his influential essay ‘Projective Verse,’ Olson urged poets to measure poetry by their own breath rather than through traditional forms. He called it “composition by field.” Eigner’s field was distinctive; he composed his free verse by drawing on what he called ‘immediacy’ and ‘force,’ what David Hinton in an essay on Eigner calls ‘contact’ wild. As long as there was sufficient force in the spacing, Eigner believed, the impact of distancing on the page could be as powerful as the words themselves. Poet Ron Sillman credits Eigner with pushing projective verse further by advancing ‘thinking’ verse rather than ‘speech-based projectivist’ poetry. Indeed, Sillman was an early founder of L-A-N-G-U-A-G-E poetry, which considers itself to be an advance on Eigner’s experiments.

Eigner wrote and published over twenty books of poems on that front porch with that typewriter. His work was first published by Robert Creeley’s Diver’s Press, then Jargon, Fulcrum (London), and Black Sparrow. His first Selected Poems was published by Oyez in 1972. Countless more poems could be found in Origin, Black Mountain Review, Granta, and other small publications. In his “The Party in the Fields. Eigner writes:

I like my friend’s house

With the driftwood picked up

near there, right on the beach I’d think it

two steps down

there

almost resembling something

on the wall

Bartlett explains that, with his father’s death and his mother’s aging, Eigner, at his older brother Richard’s urging, moved to Berkeley, California to be near his sibling as well as to take part in the area’s thriving poetry scene. He lived in Swamspscott until he was fifty-one, and moved to Berkeley in 1978. Eigner was invigorated by his newfound independence.

We learn that the poet Robert Griener befriended Eigner while teaching at Tufts University and became more than a friend when he moved to the San Francisco Bay Area at around the same time as Eigner did. Greiner was not only a champion of Eigner’s work — by editing and submitting his poetry — but he also served as Eigner’s caretaker (with his partner) in Berkeley for many years there.

When I lived in Berkeley in the ’80s I would see Eigner in the audience at the Cafe Mediterranean on Telegraph. He would sit in his wheelchair right up front and rock, his ‘wild left side’ flailing alongside the poet as he or she read. I was only 21. I didn’t have the nerve to go up to him because he was too much of a rock star, I was too much in awe. I bought Oyez Press’s Selected Poems at Cody’s and in Tuumba Press’s Flat and Round. My favorite poem in Flat and Round is:

in the morning

bird tail

below the gutter

and another one

under a high cloud

glass reflects branches

the air they ride

how much neighborhood

leaves caught me

sounding like rain

the tree on the walk

bread borne

to it

and next to the yard

mountainous over the fence

Even before he moved to Berkeley, argues Bartlett, Eigner was an influence on the coming generation of West Coast poets. As early as 1976, Charles Bernstein and Bruce Andrews included two homages to Eigner in the first issue of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E. Eigner’s essay “Approaching Things Some Calculus How Figure It of Everyday Life Experience” was followed by Clark Coolidge;s “Larry Eigner Notes.”

each line

equals

its own completion

and every line

its consequence

wholes are only made by motion

In many ways. Bartlett’s Sustaining Air is a capstone to a steady solidification of respect for the poet’s art and legacy. In 2010, Stanford University Press published the four volume, fourteen pound Collected Poems of Larry Eigner, edited by Curtis Faville and Robert Grenier, who followed that volume in 2017 with Calligraphy Typewriters: The Selected Poems of Larry Eigner for the University of Alabama Press. In 2020, University of New Mexico Press released a volume of academic essays edited by Bartlett and George Hart entitled Momentous Inconclusions: The Life and Work of Larry Eigner. Tucked behind the academic meditations, at the end of the book, sits the only collection of Eigner’s letters in one place.

At this point, the words of Boston’s late William Corbett ring even truer than they did in 2012, when he said that it is clear that Eigner’s achievement is “big enough so that it will have to be ignored by going around it.”

Kevin Gallagher is a Boston-area poet, publisher and political economist. His recent books of poetry are And Yet it Moves and The Wild Goose. He edits spoKe, a Boston annual of poetry and poetics and works as a professor of global development policy at Boston University.