Visual Arts Commentary: The Problematics of Multiculturalism at the MFA — On the Dallin Front

By Trevor Fairbrother

Boston’s MFA owns the ethical and cultural dilemma regarding the location of Cyrus Dallin’s monumental statue Appeal to the Great Spirit, acquired as a gift in 1913.

Onlookers view Cyrus Dallin’s Appeal to the Great Spirit from the sidewalk in 2021. Photo: Peter Gordon

The necessary work charted by the multiculturalism movement of the 1980s is on the front burner at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. The goal is to take difference into account by involving underrepresented voices. In the latest parlance of grant applications, strategic efforts are being made to change the dialogue on Eurocentricity and colonial legacies and to create a platform around antiracist practice. An array of incidents foregrounded problems: in June 2015 Asian Americans protested a “Kimono Wednesdays” program that they felt perpetuated racist stereotypes; in May 2019 the chaperone of 30 BIPOC middle school students reported that museum employees and visitors in the galleries made racist remarks to her group; in September 2020 the MFA, with three other museums, abruptly and preemptively postponed a Philip Guston retrospective to chew over the politicized imagery of some pictures in light of the racial justice movement.

In this period, an equestrian statue titled Appeal to the Great Spirit became contentious. The work of local artist Cyrus Dallin (1861–1944), it stands between Huntington Avenue and the MFA’s front door. Dallin sculpted it in plaster in 1908 and had it cast in bronze in Paris in 1909. In January 1912 it was temporarily installed in front of the MFA so that the Metropolitan Improvement League could raise funds to purchase it and permanently install it in a prime spot in the Back Bay Fens near Charlesgate. In 1913 a prominent collector made a sizeable contribution that guaranteed the sculpture would remain in place under the ownership of the museum.

From April 2018 to March 2019 the MFA presented a small show that appraised the institution’s wavering engagement with indigenous cultures. Titled Collecting Stories: Native American Art, the museum described it as “the first in a series of three exhibitions funded by the Henry Luce Foundation that will use understudied works from the MFA’s collection to address critical themes in American art and the formation of modern American identities.” When the museum opened to the public in 1876 its educational ambition was to represent art in all media and from all cultures. After World War I the MFA donated or lent most of its indigenous American objects to ethnographic and archaeological museums. The opening of the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC, in 2004 marked a watershed, and the MFA’s own engagement was bolstered by the inauguration of its Art of the Americas Wing in 2010.

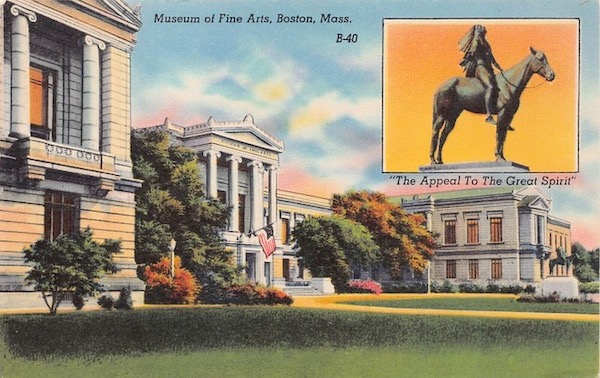

Technicolor tourist postcard featuring Dallin’s Appeal to the Great Spirit.

Collecting Stories stimulated discussion about the MFA’s monumental Dallin. The exhibition included a table-top version of Appeal, less than two feet tall. An unsigned curatorial label noted that the sculptor authorized statuettes in three sizes, and it owned up to a standoff: “Throughout his life, Dallin criticized the U.S. government’s treatment of Native peoples; however, [Appeal to the Great Spirit] still capitalized on the period myth of the ‘vanishing race,’ which portrayed indigenous peoples as disappearing in the face of modern civilization.” The conclusion about a future of doom hinged in part on the piece’s body language: “The figure sits astride a standing horse with his arms outstretched and palms open — a gesture that seems simultaneously to call for divine intervention and [to] admit defeat.” An accompanying label for the small bronze was titled “Another Perspective on Appeal to the Great Spirit.” It was signed by Dr. Jami Powell (Osage), associate curator of Native American Art, Hood Museum of Art. Powell recognized the “aesthetic beauty” of the sculpture while objecting to a narrative agenda that foretold “the decline, loss, and extinction of American Indian peoples.” There, Dallin was delivering an “inaccurate message.”

As Collecting Stories was about to close, the MFA’s director, Matthew Teitelbaum, made introductory remarks at a program about Dallin. He acknowledged that the monument divides the public: some think it a majestic, aesthetically powerful object, while some find it unwelcoming and exclusionary. With sober regard, he said that the panel discussion would not address concerns about “whether the Dallin sculpture stays up or comes down.” Thanks to that caution, the event was not a shouting match.

The notion of moving Appeal to the Great Spirit joined controversies in several states regarding historic monuments that can traumatize people from communities scarred by racialized violence. In 2017, the planned removal of a statue of General Robert E. Lee from a park in Charlottesville, Virginia, triggered a Unite the Right rally in defense of a monument commissioned in 1917 and dedicated in 1924. A self-identified white supremacist drove a car into a crowd of counter-protesters and killed one person. It was inevitable that the escalating Black Lives Matter protests would rouse Indigenous peoples to speak out against related situations, including the MFA’s Dallin. The political moment underscored longstanding efforts to counter the derogatory ethnic stereotyping generated when nonnative sports teams use Native American images and names; it also built on the discouraging aftermath of the 2016-17 Dakota Access Pipeline protests.

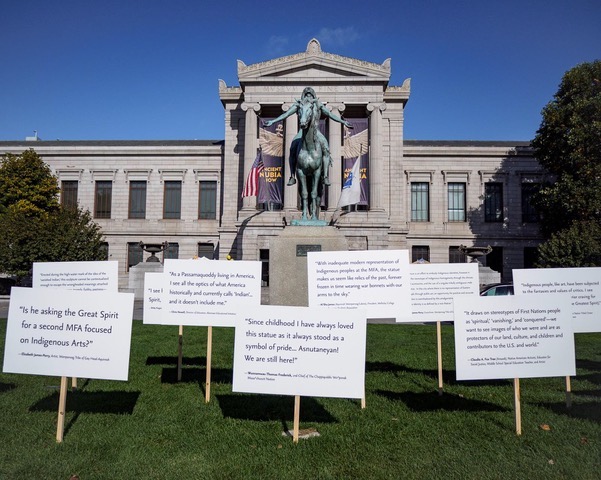

MFA’s Indigenous Peoples’ Day 2019 — placards in front of Dallin’s Appeal to the Great Spirit.

George Floyd died brutally at the hands of Minneapolis police officers in May 2020. A month later statues came down on both sides of the Atlantic. British protesters in Bristol felled a monument to Edward Colston, a 17th-century slave trader and benefactor, and threw it into the harbor. A couple of weeks later, in Washington, DC, the only outdoor sculpture honoring a Confederate general (Albert Pike) was toppled and burned. At the end of the month the Boston Art Commission voted unanimously to remove Thomas Ball’s Emancipation Memorial from Park Square. The statue, installed in 1879, depicted President Lincoln bidding a freed slave to rise from his knees. The Commission concluded that it conveyed subservience more than freedom, not least because the Black man is shirtless and wears a loin cloth while Lincoln’s formal attire connotes his power.

The MFA hosted its first Indigenous Peoples’ Day community celebration in October 2019. One initiative was to gather feedback about Dallin’s Appeal. Printed placards with signed comments about the sculpture were placed around the base and viewers were offered comment cards and invited to make their own observations. The museum later posted 17 visitor responses on the Dallin page of its website. They echoed the polarity broached by Teitelbaum at the panel discussion. One person wrote: “It tells me that the Museum isn’t for Native people like me, but for white people and their false impressions of reality.” And another, ” Always important to consider perspective, even if intentions seem good at first. White savior B[ull]S[hit].“)

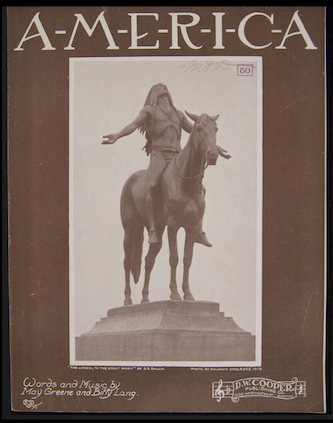

1917 sheet music published in Boston.

On July 6, 2020, the museum posted an essay about the Dallin by Joseph Zordan, a self-described “Anishinaabe and art historian,” who, in 2017, was the MFA’s Henry Luce Curatorial Intern for Museum Diversity in the Art of Americas. He pointed out that “Dallin has taken our grief as Indigenous peoples and cast and immobilized it in bronze, cursed to hang in the air forever, with lips parted and eyes frozen wide open.” On July 26, 2020, the Philadelphia Inquirer published an article on local monuments with figures of Native Americans, including Dallin’s equestrian statue Medicine Man (1899), installed in Fairmount Park in 1903. Margaret Bruchac (Nulhegan Abenaki), an anthropology professor at Penn, lamented the orthodox notion that they are truthful statements about extinction: “These statues are not made to represent or talk to living Native people. They’re made to talk to tourists and visitors.”

In June 2021 the MFA presented an exhibition to extend the dialogue from Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Garden for Boston was an unprecedented two-person outdoor intervention that temporarily reshaped the grounds surrounding the Dallin. Radiant Community by Ekua Holmes (African American) featured masses of sunflower plants intended to broadcast beauty and symbolize the power of Black self-determination. Raven Reshapes Boston: A Native Corn Garden at the MFA by Elizabeth James-Perry (Aquinnah Wampanoag) articulated the reciprocal relationship between local Indigenous people and the land, literally surrounding Dallin’s sculpture with corn plants to proclaim Algonquian beliefs and practices.

The Dallin story faded from the news cycle after 2021. There was one tangible and unprecedented addition on Huntington Avenue: a plaque giving information to passersby. It has an unsigned curatorial text and a QR code providing mobile phone users access to much information on the museum’s website. The label culminates with a comment about the sculpture’s waning status as a beloved icon: “For some, it represents a painful ‘vanishing race’ stereotype … and erases the stories of living Indigenous peoples, especially those here in Boston. We now reckon with this complicated history.” It formulates Appeal as a white man’s fantasy: “This figure appears to be a Native American man from the Great Plains…. [He is] dressed in a mix of Lakota- and Navajo-style regalia.” Dallin’s efforts as an ally to Indigenous peoples are not mentioned.

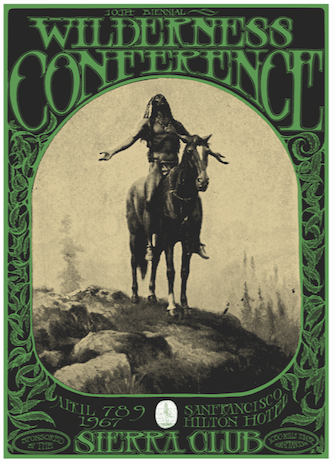

1967 Mouse Studios poster, San Francisco.

The text on the outdoor plaque feels dispiriting and censorious. The issue of negative stereotyping is unavoidable, but there is only one positive observation — that the Appeal was “beloved by generations of visitors.” Fault is found with the horseman’s apparel while ignoring the probability that Dallin intended the figure to be an emblem rather than a realistic portrait. (Some readers must be wondering, quite rightly, why I’d worry about this. It’s common knowledge that most museum visitors don’t read the labels. I recognize an institution’s impulse to write interpretative texts that jolt the presumed naivete or complacency of some visitors; on the other hand, a strident or virtue signaling attitude can be counterproductive.)

The prevailing drift is to cut Dallin no slack. Art critic Murray White often reports on contemporary efforts to disavow “monuments to colonial power.” He has described Appeal as a “chief astride a horse, arms outstretched to the heavens in a classic, clichéd victim’s pose.” (Boston Globe, January 17, 2019.) Emily C. Burns, on the other hand, favors the idea that Dallin created an artistic symbol of prayer. The interdisciplinary art historian reads Appeal as an ambivalent statement about retaining Native spirituality. For her, the figure is more survivor than victim; he is an empathic embodiment of strength of character and a stand against assimilation. (Archives of American Art Journal, Spring 2018.) Burns cites comments made by Dallin in the 1920s that conveyed an activist involvement in Indigenous rights; in one interview he said, “If we [the U.S.] are to retain our self-respect and continue to hold our place in the world, we must admit our faults and mistakes and do our utmost to make up for them.” He was the chairman of the Massachusetts Branch of the Eastern Association of Indian Affairs at this time.

Dallin’s Protest of the Sioux (1904).

Before Appeal, Dallin introduced three related equestrian statues in public places: A Signal of Peace (1890), installed in Chicago’s Lincoln Park in 1894; Medicine Man (1899), acquired by Philadelphia as noted above; and Protest of the Sioux (1904), prominently featured at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Protest featured a warrior with raised fist and a fiercely protective horse. The arrival of the fourth work in Boston prompted a popular interpretation claiming that Dallin created these four works as a “series [epitomizing] the gradual conquest of the now vanishing race.” (Art and Progress, June 1913). According to this framing, Signal shows a friendly meeting; Medicine Man introduces suspicion, Protest references active warfare, and Appeal represents the defeat of a lost cause. In February 1914, Arts & Decoration published an article titled “Cyrus E. Dallin and the North American Indian: Four Statues Which Express the Fate of a Dying Race.” There seems to be no evidence that Dallin instigated this storyline, and none that he objected to it. Consequently, the dominant discourse sees him as a participant in the mythology of doom, even though he objected to the country’s assimilationist agenda. (Sadly, his Protest of the Sioux statue in Missouri was not bronze and eventually disintegrated. Curiously, the MFA owns a bronze statuette version [21″ tall], the gift from a Brahmin family in 1967 — it is currently “Not on View.”)

I have a soft spot for the visual legacy of Dallin’s Appeal: it was a compelling image that effortlessly migrated into the commercial realm of popular culture. In 1917 the sheet music cover for AMERICA by May Greene and Billy Lang featured the work of Baldwin Coolidge, the staff photographer for the MFA. The upward glance of Coolidge’s camera nailed the epiphanic grandeur of the outdoor sculpture. The 1911 Globe article noted above said that one strong point of Appeal was “its quality as a purely American subject.” In 1916 the Miller and Arlington Wild West Show Company presented a spectacle in Boston featuring Buffalo Bill, Native Americans, cowboys and horses from the 101 Ranch of Oklahoma, and furloughed regulars from the US Cavalry and Field Artillery; there was a military pageant titled “Preparedness” and a mimic “battle with Indians.”

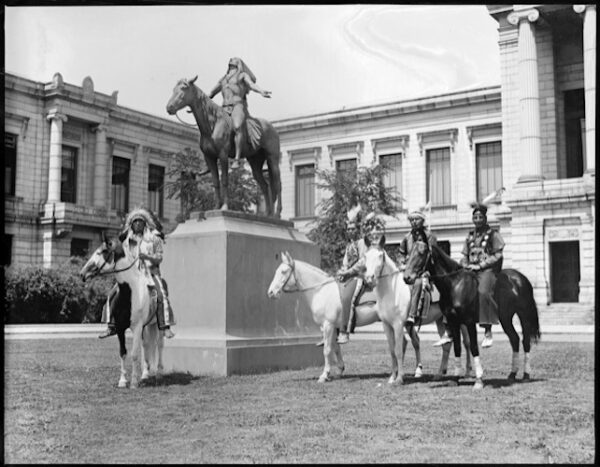

In the early 1920s four “Show Indians” posed with Dallin’s Appeal for photographer Leslie Jones. They were performers in the “101 Ranch Real Wild West Show.” Did they feel resentful toward the artist or the sculpture while doing their job? P.P. Caproni and Brother illustrated one picture from this photo opportunity with Chief Bald Eagle as the frontispiece of its 1922 catalogue of plaster reproductions. The Boston firm had already published an eight-page brochure titled American Indians and Other Sculptures by Cyrus E. Dallin in 1915: Appeal was available in two sizes, 36 or 21 inches tall.

Fast forward to 1967 and the Dallin is reborn as an emblem of countercultural redemption: a transcendent icon for beatniks, peaceniks, hippies, environmentalists, and other progressive tribes. Mouse Studios (artists Stanley Mouse and Alton Kelley) used its image on the landmark poster for a “Wilderness Conference” presented by the Sierra Club at the San Francisco Hilton Hotel in early April. I say “used its image” because I think they lifted the composition from a mass-market colored image made in the 1920s or ’30s. (The cheap prints probably pirated the image of the sculpture from a black-and-white Detroit Publishing Co. photograph, then added color and surrounded it with an imaginary hilltop setting.)

1922 photo of four “Show Indians” posed with Dallin’s Appeal. Photo: Leslie Jones

My point is that Mouse Studios found magic in the Dallin and translated it for the city that three months earlier hosted the Human Be-In in Golden Gate Park. Rick Griffin’s poster for that event included a drawing of a Dallinesque Indian on horseback, one hand holding up a blanket, the other steadying the guitar strung round his neck; part of the small-scale text decorating the edge reads, “Bring Photos of Personal Saints and Gurus and Heroes of the Underground.” In 1967, what were Indigenous people thinking or saying about the reimagining of Appeal on the “Wilderness” poster? What did they make of Jimi Hendrix’s fringed suede jackets and turquoise jewelry? How was the poster connected to the burgeoning Red Power Movement?

People see art objects according to their personal knowledge and background and the slant of the prevailing zeitgeist. Whether encountered as a sculpture or a pictorial reproduction, Appeal can be taken as an artist’s visual metaphor of heartfelt invocation. Now there is a growing sociopolitical climate that freights it with coded messages hurtful or offensive to Indigenous peoples. The MFA owns the ethical and cultural dilemma about the location of the monumental version acquired as a gift in 1913. Relocating it is entirely feasible. If the front courtyard is emptied, it will be hard work to contrive a felicitous “better” solution.

Trevor Fairbrother is a curator and writer. In 2018 he contributed an essay to T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America, the catalogue for the Peabody Essex Museum’s eponymous exhibition, curated by Karen Kramer. Trevor Fairbrother © 2024

What an important important essay! Immense thanks for all the time and work putting it together. Cyrus Dallin sounds like a great person, and I am all on the side of keeping “Appeal to the Great Spirit” exactly where it stands.

A bit oft-putting and disingenuous by omission. Missing is the complicity (or not) of the author in the above dialog while he was serving as a curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (1981–1996).

Great observation. When I began, as a novice researcher assistant in the Department of American Paintings, the MFA’s curators took their departmental boundaries very seriously. Dallin’s work fell within the purview of the Department of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture (created in 1970). My area of expertise was John Singer Sargent, whose works were divided between three fiefdoms: I was in the one with the oil paintings; the sculptural elements of his mural decorations were in the department just named; and his drawings and watercolors were in the Department of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

During my last years at the MFA, I was curator in the Department of Contemporary Art: in that role I was able to acquire contemporary sculpture but photographs were dissuaded. The working solution was that I pursued work not deemed a priority by the Department of Prints, Drawings and Photograph. Thus, I helped the MFA acquire its first photo-based works by Catherine Opie, Lyle Ashton Harris, Cindy Sherman, Thomas Struth, Sherrie Levine, Robert Mapplethorpe, Barbara Kruger, Lorna Simpson, Sophie Calle, Nayland Blake, Louise Lawler, Ana Mendieta, Nan Goldin, and William Wegman. But Dallin? He was never an option for me!

Regarding the fiefdoms that Fairbrother describes there is an irony. He delineates borders that were not crossed. Prior to Ken Moffett’s appointment in 1971 the museum had no defined strategy to collect modern art. Perry Rathbone did so sporadically. Modernism. however, was an agenda for the department of prints and drawings.

Regarding photography, a gift of nude photographs by Stieglitz of his wife O’Keeffe were “lost” in the basement. Trevor’s list of photo acquisitions is stunning. It implies that on his watch the photography curator (Cliff Ackley?) was not getting the job done. There is more to it than that. Factor in director Malcolm Rogers, who had his thumb on the curatorial scales. He promoted Cars, Guitars, Wallace and Gromit, Yusuf Karsh, and Herb Ritts. Perry dabbled in modernism, but there has not been a director savvy about issues of modern and contemporary art until Matthew Teitelbaum. Because he was in the midst of this, I would love to read Trevor’s take on the MFA’s modernist holy mess.