Doc Talk: Childhood Lost and Found in “Anselm”

By Peter Keough

This is a magnificent 3D documentary about the thought and work of the acclaimed German painter and sculptor Anselm Kiefer.

Anselm. Directed by Wim Wenders. At the Kendall Square Cinema.

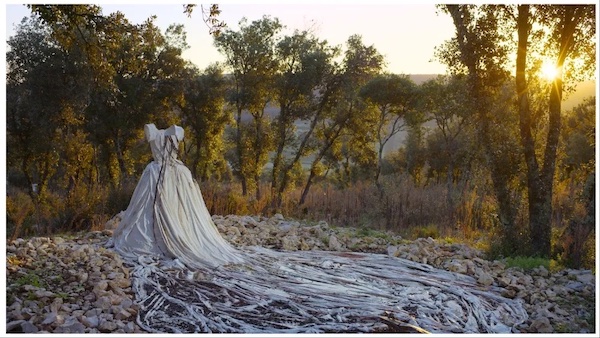

Scene from Anselm. Photo: Road Movies/Wim Wenders

When Anselm Kiefer first appears in Wim Wenders’s magnificent 3D documentary about him and his work, he is dwarfed by one of his giant, grim canvases in his atelier in Crissy outside Paris. The artist rides off on a bicycle through the ranks and corridors of his artworks, stored like the castoffs of history warehoused at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). The bicycle will return at various times in the course of the film. So will Kiefer — as the septuagenarian he is today, as a young man played by his son Daniel, and as a child played by the director’s great-nephew Anton Wenders.

Kiefer’s own childhood — born like Wenders in Germany in 1945 — was spent in part among ruins, though judging from the archival footage of children romping through bomb craters, rebar, shattered masonry, and piles of rubble that form part of the film’s rich composition — it was more like the playground of possibility of John Boorman’s Hope and Glory (1987) than the despair of Roberto Rossellini’s Germany Year Zero (1948) .

These scenes and the film’s mood and themes recall the opening lines of Wings of Desire (1987), a recitation by Bruno Ganz of Peter Handke’s “Lied Vom Kindsein” (“Song of Childhood”): “When the child was a child, it didn’t know it was a child. Everything was full of life, and all life was one…” Kiefer’s work also recalls the monolith that divided Berlin so prominently during Wenders’s earlier film: the Berliner Mauer that graffiti artists had transformed into art.

That example of urban transformation could be seen as a plebeian version of Kiefer’s own career, which Wenders covers impressionistically, peripatetically, poetically, and without overt commentary. It is a dreamlike voyage, concrete and numinous, elevated by eerie, elegiacal choral music by Leonard Küßner reminiscent of that composed by Zbigniew Preissner for the films of Krzysztof Kieslowski.

Wenders begins with his subject’s earliest works fashioned at his atelier in the Odenwald forest in the ’70s, a looming roughhewn attic in which in one reenactment Kiefer toils at a projection onto the canvas of the atelier itself, a kind of solipsistic recession into his own creativity.

But, as a protégé of Joseph Beuys, Kiefer would delve into German mythology and history, which he came to believe had been hijacked by the Nazis. His iconography included heroes and villains ranging from Siegfried to Horst Wessel, images which he insisted he was trying to reclaim and reconsider. As seen in period interviews — that Wenders shows on an old TV or projected on sheets spread between trees — Kiefer was understandably dismayed when critics, especially those in Germany, accused him not just of confronting the Nazi cultural appropriation, but embracing it.

Eventually Kiefer fled his homeland for France where he established a giant theme park of sorts near Barjac in Southern France, 96 acres of artworks and installations. It is the setting of some of the film’s most astonishing images. Seen today, Kiefer tours Barjac and other cavernous repositories of his canvases, sculptures, and artifacts, or creates enormous new ones with flamethrowers and vats of molten lead, a process reminiscent, though on a more Olympian scale, of the artist in Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Mystery of Picasso (1956).

He opens a book he created about one of his obsessions, the philosopher Martin Heidegger, a giant of German existential thought who has been disgraced over the years by embarrassing disclosures of his Nazi connections. Each page features an encroachment, via a black tarry miasma of the subject’s brain being devoured by cancer. A disarming contrast follows when Kiefer lovingly turns the pages of another book, this one a bold photo album with pictures of himself as a child and his family.

Despite the latter’s hint of nostalgia and sentiment, people seem absent in much of Kiefer’s later work, except perhaps in the form of the series of plastered wedding gowns, headless or crowned with branches, that look like Pompeian casualties or participants in Druidic fertility rites. In lieu of the human figure there are often words. Handwritten excepts from such Paul Celan poems as “Death Fugue” are scrawled across paintings much like the text of lyrics of a children’s song by Joseph Wulf included in Jonathan Glazer’s recently released film The Zone of Interest (Celan and Wulf, both Holocaust survivors, ultimately committed suicide).

Towards the end of Anselm, Kiefer appears alone, lying in a towering room, empty except for a pair of monumental paintings on the walls that are as grey as the void that surrounds him. There’s a cut to a shot of the artist as a child, alone again, but in a field full of sunflowers, and then a cut to a painting of himself, younger, again lying down in a circle of sunflowers — but which are charred and monstrous.

In a later segment, Kiefer speculates about the nature of existence and nothingness. His questions are similar to those that the child asks at the beginning of Wenders’s Wings of Desire: “Isn’t life under the sun just a dream? Isn’t what I see, hear, and smell only the illusion of a world before the world?” Questions that not even a lifetime of the greatest art and genius can answer.

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He had been the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, most recently For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

Nice review with comparisons of Keifer’s art to other works and of the influences of Heidegger and Celan. It should be noted that the use of 3D enhances the experience of these massive artworks nicely, as it did with dance and space in Wenders’ previous 3D documentary on Pina Bausch, Pina.

Now is the time to take advantage of that experience, not when it comes to your plasma screen.

After this, I watched another documentary, Over You Cities Grass Will Grow. At about 60 minutes, the film focuses primarily on Kiefer’s process of building the elaborate installations, paintings, building-like structures, and network of tunnels that comprise Barjac, his 200-acre art studio/city. It’s a great addition, and though unavailable online, there is one copy available on the Minuteman Library network.

thanks for the tips!