Film Review: “Maestro” — Scenes from a Marriage

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Maestro is raw and unsparing but also full of understanding, grace, and honesty. This compelling drama brings to life the man and woman behind an extraordinary amount of musical activity, with many of their shortcomings and contradictions fully intact.

Maestro, directed by Bradley Cooper. Streaming on Netflix

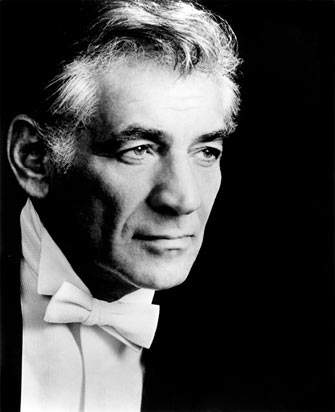

Leonard Bernstein — there’s plenty about his life that is unknown to the wider public. Photo: Wiki Common

The genre of the classical music biopic is small and generally unimpressive. Whether well-intentioned (Copying Beethoven) or over-the-top (Lisztomania), these movies rarely do justice to their subjects. Triumphs (like Amadeus) are the exception, not the rule.

Bradley Cooper’s Maestro isn’t quite the second coming of Amadeus, partly because it’s less a musical biography than a drama about two people, one of whom happens to be a leading classical musician. That the person in question is Leonard Bernstein makes the relative absence of musical performances in the film a bit surprising: after all, Bernstein was a regular presence on network TV during the 1950s and ’60s.

Then, again, so much of his teaching and conducting is readily available on YouTube that one doesn’t entirely mind the lack of recreations of his great performances — and the risks they entail — in an already packed, two-plus-hour-long film.

Besides, there’s plenty about Bernstein and his life that is unknown to the wider public. Maestro, which examines the composer/conductor/pianist’s life through the prism of his marriage to Felicia Montealegre Cohn, endeavors to bring some of that to life. The effort, which Cooper directed and in which he stars as Bernstein, is, like its subject, imperfect. But it’s deeply affecting and stands as a stirring testament to the filmmaker’s remarkable storytelling abilities.

The tale’s fundamental conflict is apparent almost from the start: when we meet Lenny on the cusp of his sensational New York Philharmonic debut in 1943, he’s in bed with a male lover (Matt Bomer’s David Oppenheim). A few scenes later, he meets Felicia (played by a luminous, commanding Carey Mulligan), an aspiring actress, at a party and the two are, seemingly, inseparable.

Scenes on two stages — at Felicia’s theater and, later, a fantasy rehearsal of Lenny’s ballet Fancy Free — jump start the action and, from here Maestro moves quickly across the decades.

Lenny and Felicia, now married, are juggling their careers. His takes priority, though he struggles to balance the competing demands of composing (a solitary activity) and performing (a public one). As the years go by, Lenny’s homosexual proclivities put increasing strains on the marriage.

These indiscretions culminate in a ferocious argument one Thanksgiving morning in the couple’s bedroom in The Dakota during which an inflatable Snoopy balloon makes an impromptu appearance. Ultimately, the pair separate, though by the time Felicia is diagnosed with cancer, they’ve reconciled.

For anyone who’s read any of the several excellent Bernstein biographies available, none of this (aside from Snoopy’s cameo) will come as a surprise. What is astonishing, though, is the degree to which Cooper and co-writer Josh Singer have sourced their screenplay.

Nearly everything that appears onscreen or is said is documented in the historical record. Even events that appear out of sequence (like Lenny’s relationship with Tom Cothran and Felicia jumping, fully-clothed, into the family’s pool at their Fairfield, Connecticut, home — she did this after her husband completed his Kaddish Symphony, not Mass) are recognizable and can be easily traced. Though the writers take some dramatic license with the ordering of things, Maestro is breathtakingly accurate in its particulars.

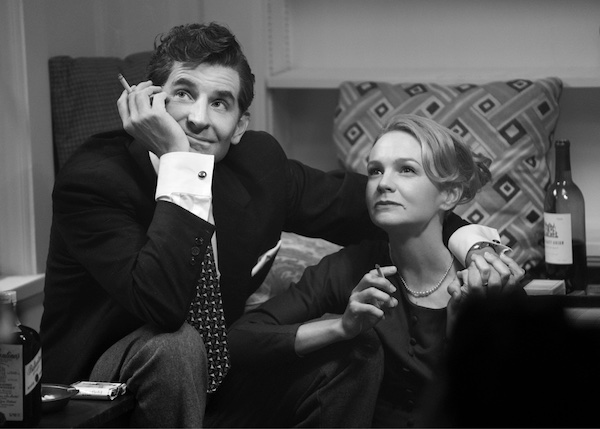

Bradley Cooper as Leonard Bernstein and Carey Mulligan as Felicia Montealegre. Photo: Michael McDonald/Netflix

Additionally, filming locations lend Maestro a rare air of authenticity. Scenes at the family home in Fairfield, at Tanglewood, and at Ely Cathedral were taped on-site. The mix of black-and-white and color footage lends the movie’s various eras pop and immediacy. The closing credits clip of Lenny conducting the Boston Symphony at Tanglewood in 1988 packs a similar emotional punch to watching Ray Charles singing “Georgia on My Mind” at the end of Ray.

All of which makes Maestro’s omissions especially frustrating.

Chief among these is a complete lack of acknowledgment of Lenny and Felicia’s shared political activism. His friendship with the Kennedys (Jackie commissioned Mass for the opening of the Kennedy Center), appearance at the Stars for Freedom March in Selma in 1965, and involvement in any number of anti–Vietnam War protests go completely unmentioned.

So does Felicia’s work with the A.C.L.U., her engagement with Eugene McCarthy’s ill-fated 1968 presidential campaign, and her infamous 1970 fundraiser for the legal defense fund of the Black Panthers.

True, Lenny crashed the latter and the two were subsequently pilloried in Tom Wolfe’s Radical Chic. But Wolfe’s vicious interpretation aside, the couple’s political and social involvements weren’t trendy hobbies. Rather, they stood near the core of their identities as engaged global citizens. The absence of this facet of their relationship from Maestro’s storyline, while understandable from a streamlined, narrative perspective, has a flattening effect on the characters.

So does the movie’s focus on Bernstein’s dalliances with men as the sole cause of the couple’s marital strife. By any measure, Lenny and Felicia had a complex union and it was driven to the breaking point by his indiscretions. And it’s true he treated her vilely at times, especially in the years leading up to their separation. But Lenny wasn’t the pure villain Maestro makes him out to be, and the issue of his sexuality wasn’t the only strain on their marriage.

Again, one can appreciate the need of Maestro’s creative team to condense a sprawling, multifaceted story to fit into a set timeframe. But even a brief recognition of some of these issues (like Bernstein manager Harry Kraut’s encouragement of his client to carry on affairs with younger men) might have added a welcome layer or two of context to the proceedings.

Additionally, one would have appreciated a greater emphasis on Bernstein’s Jewish heritage in the film. There’s a brief mention of that early on, when his mentor, Serge Koussevitzky (Yasen Peyankov), encourages his protégé to change his name to Burns (“They’ll never give an orchestra to a Bernstein,” he prophesies — wrongly, as things turn out). Aside from this allusion, however, precious little screen time is devoted to the issue, despite its elemental importance to Bernstein’s musical and personal identities.

That said, Maestro’s lead performances are impressive.

As Bernstein, Cooper is excellent, if not always pitch-perfect: in his conducting scenes, he often seems to be mimicking Bernstein rather than truly channeling him — a stunning, six-minute-long recreation of Lenny’s 1973 Ely Cathedral performance of Gustav Mahler’s Second Symphony notwithstanding. That said, there’s a strong physical resemblance between the two and the actor’s largely got Lenny’s mannerisms and Boston Brahmin accent down pat.

Mulligan’s Felicia, though, steals every scene she’s in (appropriately, the actress gets top billing). The real Felicia was no pushover: according to every reputable biographical record, she was Lenny’s intellectual and artistic equal, his sounding board, his anchor, and the love of his life. She also knew exactly what she was getting into when she married him, which makes the late-in-life realization of what she gave up for him — and how little she originally thought it would cost — all the more heartbreaking.

Bradley Cooper as Leonard Bernstein and Carey Mulligan as Felicia Montealegre in Maestro Photo: Jason McDonald/Netflix

Articulating that aspect of her relationship with Lenny is, perhaps, Maestro’s great theatrical achievement. “The life of every individual,” Arthur Schopenhauer opined, “is really a tragedy.” That was true of Felicia — Mulligan’s portrayal of her demise is shattering — and also of Lenny: despite his undeniable musical genius, his personal demons (and his guilt about Felicia’s death) literally haunted him and his music until the day he died in 1990.

Though Cooper and Mulligan own the film and there are additional standout performances (particularly Sarah Silverman’s Shirley Bernstein and Maya Hawke’s Jamie Bernstein), the movie’s other big star is Bernstein’s music. True, we don’t get a blow-by-blow account of Lenny writing his greatest hits. Instead, snatches of them, all thoughtfully placed, touchingly underline Maestro’s narrative. It’s safe to say that no amount of dialogue or exposition could have rendered this fare more powerfully, especially the selections from A Quiet Place and The Age of Anxiety.

While not definitive, what Cooper has given us is a compelling drama that brings to life the man and woman behind an extraordinary amount of musical activity, with many of their shortcomings and contradictions fully intact. It is raw and unsparing but also full of understanding, grace, and honesty. Though necessarily incomplete, Maestro ultimately pays Lenny and — finally, especially, after all these years — Felicia a respectful, fitting tribute.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Bradley Cooper, Carey Mulligan, Felicia Montealegre, Leonard Bernstein

A beautifully done review — the movie has really divided the audience, if social media is any indication. But Jonathan really captures what is extraordinary about the film and some of the hard decisions Cooper made as a director (apparently, the Black Panthers fund-raiser was filmed but later cut). And those performances!

This review of Leonard Bernstein’s correspondence is way more interesting than the movie.

Excellent review, Jon! there was no way in the world a film could have packed it all in — maybe if it were a miniseries. There was not enough for me about Boston or the Bernstein family or the Second World War or his lifelong involvement with Israel. And what about her family and her place in it? How did she get to live in Greenwich village in 1944? What role did money play in her life and in the relationship? So many unanswered questions and yet the film gives us a lot to chew on in an intelligent and serious way. It’s not for people expecting a biopic.

Jon, two extraordinary reviews in one week! I am wildly impressed. Really thoughtful pieces.