Visual Arts Review: “50 Years and Forward: Works on Paper Acquisitions” at The Clark

By Charles Guiliano

Plan to linger over every moment of this revelatory, diverse, and understated special exhibition.

Édouard Manet, Exotic Flower (Woman in a Mantilla), 1868. Photo: The Clark

When The Clark Art Institute opened in 1955, it had 500 drawings and 1,400 prints, totaling 1,900 works on paper. In the past 50 years, 4,000 works on paper have been added — more than double the museum’s founding gift.

50 Years and Forward: Works on Paper Acquisitions (through March 10, 2024) marks the 50th anniversary of the Manton Research Center — the home of the works on paper collection — with a selection of prints, drawings, and photographs acquired between 1973 and 2023.

While modest in scale, hung in just half of the special exhibition galleries, this understated and scholarly show is the result of a rare curatorial initiative. It is the Institute’s major winter exhibition, mounted from the months of January to March, when The Clark has free admission.

While the exhibition is labor intensive it is cost effective because there will be no expensive loans. The curator, Anne Leonard, led a media tour of the exhibition discussing key works and answering daunting technical questions about conserving and exhibiting ultra-fragile works on paper. In order to keep these works “fresh for future generations,” they may be shown no more than every five years for a few months under strict conditions. Regarding works with color, the restriction is every 10 years. For exhibitions, the works need to be framed, which entails cutting mats and nonreflective, UV resistant, museum glass. After the exhibition the works are removed from the frames and returned to storage in archival boxes, which may be viewed by appointment. (Note: The Clark’s entire collection is viewable online.).

James Van Der Zee, Wedding Day, Harlem, 1926. Photo: The Clark

During the tour, I commented that the galleries seemed to be relatively bright, given conservation requirements. Leonard took that as a compliment to be passed along to the show’s lighting designers and installers. The rows of lights have been arranged to beam straight down and to reflect, to a degree, up from the floor. Each work has been individually metered; the lighting must meet a strict standard. Given these demands, the pieces have been given a wonderfully even and accessible presentation.

To view the Book of Kells, at Trinity College in Dublin, for example, first one has to adjust to the dark. You are then given about a minute to view the page on display before being nudged along by the next visitor. Curators turn the page each day.

The selection on view has been drawn from several areas of strength in The Clark’s collection. The result is a lineup of exquisite works fit for even the most demanding connoisseurs. There is no attempt to provide any connective tissue to this sweeping show, which moves from the Renaissance to the 19th century. The exhibition simply invites visitors to admire a rich display of the museum’s rarely seen crown jewels. Which, in its own way, proves to be spectacular.

Overall, The Clark is known for its prominent gathering of French art. There is also a strong section of works from the Italian Renaissance through the Baroque. Through a bequest, the museum has most of the prints of Albrecht Dürer. A section here shows how Goya influenced Manet. In 1998 The Clark began to acquire photography, from its inception in the 1830s through roughly 1900. Such rules, however, are made to be broken via bequests and acquisitions of exceptional quality. Leonard emphasized that there is a high bar for what is accepted for the collection.

Many of the drawings on display are studies for paintings and sculptures. There is a grid, for instance, over Giorgio Vasari’s small drawing Incredulity of St. Thomas (1569). It was used to enlarge an idea from sketch to finished work. Rosa Bonheur’s Study of a Lion’s Head (c. 1872–75) is a similar work in progress. The drawing is a window into the artist’s development of what would become a detail in a painting.

Hilaire Ledru, The Painful Farewell, or Lesurques’s Farewell to His Family, c. 1796–1802. Photo: The Clark

Works such as these were never intended to be exhibited. Only some of the show’s drawings and all of its prints represent finished objects. Until the contemporary era, prints and drawings were never framed or displayed. Now collectors treat them like paintings, sometimes with dire consequences.

Touring the exhibition I had a riveting first encounter with a relatively large panorama, The Baggage Train (1516-18) by Albrecht Altdorfer. For a woodcut, the work’s scale and detail are arresting. Leonard explained that the piece, which conveys what it takes to keep an army on the move, is composed of vertical blocks printed on separate sheets of paper. These have been merged seamlessly.

Hilaire Ledru’s The Painful Farewell, or Lesurques’s Farewell to His Family (c. 1796–1802) is a relatively rare finished drawing in neoclassical style. The intent of the work is to evoke pathos; it taps into narratives inspired by the Reign of Terror. The image depicts a wrongly accused murderer with his family on the night before the guillotine. It was a matter of mistaken identity; Lesurques was posthumously exonerated.

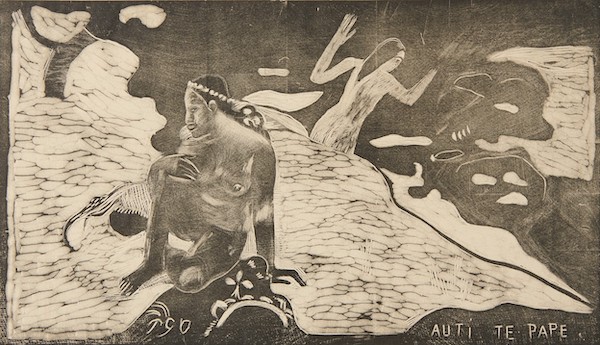

Paul Gauguin, Auti Te Pape (Women at the River) from the Noa Noa suite, 1893–94. Photo: The Clark

There is a section in 50 Years and Forward that compares and contrasts prints of Francisco de Goya and Édouard Manet. Influenced by Goya, the French artist ended up ineptly emulating Goya’s aquatint technique. It takes no more than a glance to confirm that Manet’s Exotic Flower (Woman in a Mantilla) (1868) lacks the finesse of the Spaniard’s mastery of printmaking.

The final gallery, about a third of the overall exhibition space, is devoted to photography. The collection was founded in 1998 with the acquisition of Gustave Le Gray’s Brig on the Water (1856). By contemporary standards it is an unassuming study of sea and sky. Leonard informed us that it was one of the most famous photographs of its day, admired as a great technical accomplishment because it captured the sea and sky simultaneously. It evokes moonlight but was created in daylight.

Gustave Le Gray, Brig on the Water (1856). Photo: The Clark

Berenice Abbott is a photographer who doesn’t fit into The Clark’s timeline. On the museum’s website I viewed the 406 works in a bequest. Of these, four portraits are on view in the show, one of which portrays photographer Jean-Eugène-Auguste Atget, who influenced Abbott’s work.

The Clark has a mandate to represent images — from Reconstruction through the Harlem Renaissance — of how African Americans see themselves. These are primarily portraits, and one on view is James Van Der Zee’s Wedding Day Harlem, 1926. Using a double negative, he included a surreal image of their future family.

Plan to linger over every moment of this revelatory, diverse, and understated special exhibition. Shows like this only come around once every five to 10 years.

Charles Giuliano has just published Annisquam: Pip and Me Coming of Age.

Very good review, important to remind Clark members that these exhibitions have a limited time frame, & are not to be missed, but likely will be as people wait,& then say “it’s over already? “