Film Review: “The Boy and the Heron” — How Do You Live?

By Nicole Veneto

The Boy and the Heron is a work of true beauty that fits squarely within veteran director Hayao Miyazaki’s gorgeous and emotionally resonant oeuvre.

The Boy and the Heron, playing in theaters across America on December 8.

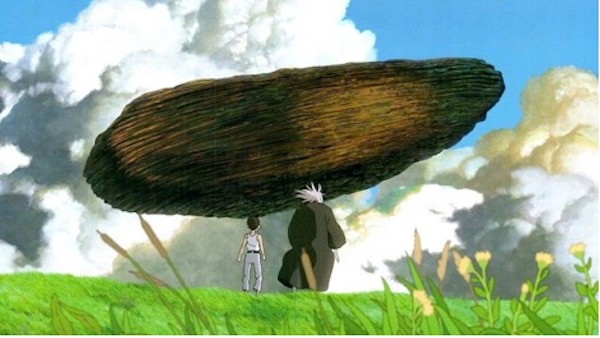

A scene from Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron. Photo: GKIDS

In an interview with Vanity Fair ahead of the release of Killers of the Flower Moon, Martin Scorsese said, “I’m old. I read stuff. I see things. I want to tell stories, and there’s no more time. [Akira] Kurosawa, when he got his Oscar, when George [Lucas] and Steven [Spielberg] gave it to him, he said, ‘I’m only now beginning to see the possibility of what cinema could be, and it’s too late.’ He was 83. At the time, I said, ‘What does he mean?’ Now I know what he means.” At 81, Marty’s statement came as a sobering reminder that there are only a finite number of films left we can expect from one of the greatest living directors before he is gone.

I had Marty’s words in mind all throughout The Boy and the Heron, the newest film from acclaimed director Hayao Miyazaki, a man whose own contributions to the cinematic art form (and animation specifically) cannot be overstated. He is one of those incredibly rare directors who has never made a single film that was less than masterful throughout his entire career. Miyazaki’s feature output, starting with his 1979 adaptation of Monkey Punch’s Lupin III series with The Castle of Cagliostro and moving onto his previous film, 2011’s The Wind Rises, include several of the greatest animated features ever made.

The director’s talent has managed to transcend cultural boundaries to great success in the West: his films have been cited as direct inspiration by Pixar for how they go about making their own movies. He famously threatened one Harvey “Scissorhands” Weinstein, when Miramax attempted to cut Princess Mononoke down to 90 minutes, by gifting him a samurai sword with a single unambiguous note: “No cuts.” My own childhood wouldn’t have been what it was without Miyazaki’s films either — being the imaginative little girl that I was, whenever I’d watch the rented copy of Kiki’s Delivery Service from my local video store I would stick a broom atop the armrests of our adjacent living room couches to pantomime riding a broomstick. And to this day, I can’t get through Howl’s Moving Castle without sobbing when Sophie tells a young Howl to “find me in the future.”

The Boy and the Heron is Miyazaki at his most autobiographical, partly inspired by Genzaburō Yoshino’s 1937 novel How Do You Live? (the translation of the film’s original Japanese title), which Miyazaki read as a young boy growing up in postwar Japan. Along with his concerns about environmentalism and fascination with girlhood, antiwar themes have continually permeated Miyazaki’s work (Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Porco Rosso, Howl’s Moving Castle, etc.). These interests clearly reflect his own upbringing. The film opens in the midst of the Pacific War as 12-year-old Mahito (voiced by Soma Santoki in Japanese and Luca Padovan in English) races to the hospital his mother works at as it is engulfed in a fiery inferno that kills her. A year later, Mahito’s father Shoichi (Takuya Kimura/Christian Bale), who runs an air weapons arsenal, remarries Mahito’s aunt Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura/Gemma Chan) and moves them out to the countryside to live on his late mother’s grand estate alongside a cadre of elderly maids. Still grieving his mother’s death, Mahito struggles to adjust to his new surroundings, quietly unable to accept the now pregnant Natsuko as a viable maternal figure, despite her best efforts to connect with him.

While wandering the estate grounds, Mahito is pestered by a talking Grey Heron (Masaki Suda/Robert Pattinson), whom he follows to a sealed-off tower on the edge of the estate. According to one of the old maids, Kiriko (Ko Shibasaki/Florence Pugh), the decrepit tower was built by Mahito’s granduncle, a famous architect who disappeared one day around the tower’s vicinity. One morning, Mahito sees Natsuko walking into the woods toward the tower; shortly after, she goes missing as well. Before he can join the search party, Mahito is waylaid by the Grey Heron, who taunts him that his mother and Natsuko are alive inside the tower waiting for him. Faced with a chance to see his mother again and save Natsuko, Mahito embarks on a grand adventure in a magical world inhabited by bumbling, man-eating parakeets, young doppelgängers, and a mysterious wizard (Shōhei Hino/Mark Hamill) seemingly in control of this alternate reality.

If there’s one thing that’s abundantly clear, it’s that mortality is very much on the 82-year-old Miyazaki’s mind, and the looming shadow of his own death haunts every frame of The Boy and the Heron. Not unlike what Scorsese does with Killers of the Flower Moon, Miyazaki is clearly reckoning with his own legacy and how his work fits into artistic and cultural landscapes of the future. Who will carry on this legacy after he’s gone? This is not to say that The Boy and the Heron is a dour movie whatsoever — quite the opposite actually. A passionate celebration of life and the inherent beauty of being alive runs throughout every one of Miyazaki’s films. The Boy and the Heron is no exception. As its original Japanese title posits, the film questions how you go about living in a world that is often rife with pain, death, violence, and isolation.

Interestingly, the answer to that question seems to be partly inspired by Miyazki’s own protégé, Evangelion creator Hideaki Anno, who got his start in animation working on the God Warrior’s attack sequence in Nausicaä. The first half of Evangelion 3.0+1.0: Thrice Upon a Time is a Ghibli-inspired affair that makes use of the psychological/existential horror the series is infamous for in order to hammer home that being alive — the flowers and trees that grow year after year, the connections we forge with other people, human resilience and community — is itself a beautiful thing. Even after we’re gone, the love and the experiences and the art we’ve made will live on for generations to come. The Boy and the Heron is a case of the master taking a page from his student, drawing on the lessons he imparted to him and reintegrating them back into what could very well be his swan song. As always, longtime collaborator Joe Hisashi provides the score, noticeably more reserved compared to the bombastic nature of Castle in the Sky or Princess Mononoke save for a haunting choral refrain heavily featured in the film’s trailers.

The Boy and the Heron lives up to what you expect from Miyazaki. Though keep in mind that this film is not particularly interested in the cutesy, easily marketable tenderness contained in such works as My Neighbor Totoro and Ponyo. Instead, it reflects the violent maturity of Princess Mononoke or even Spirited Away. (One could even argue that The Boy and the Heron plays like a gender-swapped retelling of his Oscar winning masterpiece.) Though the perpetually unretired Miyazaki claims to be working on another film, he is well aware that he is entering his twilight years. There will come a day when we all wake up and discover that Hayao Miyazaki is no longer with us, and that’s scary to even think about for me. 2023 has been a year marked with death, from the sudden losses of childhood heroes (Paul Reubens, aka Pee-wee Herman) and cinema enfant terribles (William Friedkin) to the unfathomable horrors of war that currently populate our social media timelines. So it is heartening to have a work of enlivening beauty that only a true master of animation could create.

Nicole Veneto graduated from Brandeis University with an MA in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, concentrating on feminist media studies. Her writing has been featured in MAI Feminism & Visual Culture, Film Matters Magazine, and Boston University’s Hoochie Reader. She’s the co-host of the podcast Marvelous! Or, the Death of Cinema. You can follow her on Letterboxd and her podcast on Twitter @MarvelousDeath.