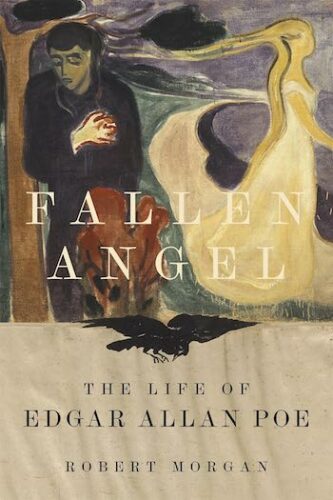

Book Review: “Fallen Angel” — Edgar Allan Poe’s “Black Electricity of Guilt”

By Bill Littlefield

Robert Morgan has written a fascinating reconsideration of the life of Edgar Allan Poe.

Fallen Angel: The Life of Edgar Allan Poe by Robert Morgan. Louisiana State University Press, 382 pages.

Part of Edgar Allan Poe’s grand achievement, according to Robert Morgan, is “exposing the Imp of the Perverse in us all.” No wonder the author felt that, despite the considerable attention Poe has received from biographers, critics, and readers delighted to be scared silly by stories like “The Tell-Tale Heart,” an ambitious reconsideration was due.

As Morgan demonstrates in his fascinating account of Poe’s life, one especially powerful and persistent “imp” at Poe’s own center was his irresolvable and tortured attitude toward women and marriage. From boyhood, Poe’s relationship with women, beginning with his mother, provoked in him all manner of contradictory impulses. Throughout his life he sought the security of a union with one woman or another, sometimes several at once, while simultaneously feeling terrified by the idea and the fact of marriage. Morgan finds in Poe’s letters as well as in his art “evidence of his emotional desperation, reaching for something stable, forgiveness, from the damnation he was certain he’d earned.” Poe blamed himself for the early death of his mother, and the even earlier death of his cousin, Virginia, whom Poe married when she was 13. The work Poe produced was charged, according to Morgan, with “the black electricity of guilt,” because the writer “understood that just when you expect it least, the Imp of the Perverse will appear.” Poe’s “attempts to escape to an artificial paradise” drove his art.

Morgan makes a convincing case for this thesis by thoughtfully probing Poe’s fiction, essays, and poetry. He convincingly argues that Poe was far more than a superb and popular entertainer; his stories and poems offered insight not only into the author’s own “imps” but into the darker nooks and crannies of his culture and his readers, many of whom may have been unaware of the psychological depths into which Poe was peering. Morgan also offers a thorough account of Poe’s daily life, which was often characterized by illness, poverty, mockery, and rejection.

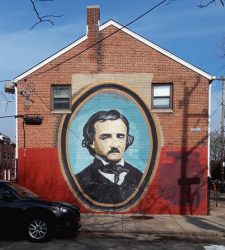

Mural near Edgar Allan Poe’s house in Philadelphia.

Then there is the attempt to set at least some of the sensational record straight. According to Morgan, the popular contention that Poe drank himself to death in Baltimore was produced and circulated by his literary enemies. Morgan has assembled evidence that suggests Poe drank no alcohol during the days before his death. He was fatally ill, probably with tubercular meningitis, an infection of the brain that resulted from contact throughout his life with people who’d suffered from the illness. Poe eventually died of tuberculosis.

Late in Fallen Angel Morgan observes that the poet’s “imagination hampered him in the actual business of living.” The extent of the understatement is spectacular. Poe’s life was often no less a horror than the lives of the characters who are buried alive or haunted by demon lovers in his poetry and his stories. His inclination to drink despite — or perhaps because of — the violence and irrational outbursts alcohol provoked in him is only one bit of evidence of the self-destructive side of his complicated psyche. Poe was 40 when he died. That he lived as long as he did is remarkable. That he created such an enduring and influential body of work — poems, stories, literary criticism — is astonishing. Fallen Angel celebrates the value of that work as it treats with candor and respect an author who has so often been misunderstood. He concludes the biography with this sentence: “Poe is fun.”

Bill Littlefield, late the host of NPR’s “Only A Game,” has worked with the Emerson Prison Initiative since 2018. His most recent novel is Mercy (Black Rose Writing, 2022)

Tagged: Edgar Allan Poe, Louisiana State University Press, biography