Book Review: “Satori in Paris” — A Minor Work From an Undisputed Alpha Beat

By David Daniel

Jack Kerouac’s best work is often driven by a hunger for spiritual nourishment: the soul food his protagonists occasionally find in friendships, in jazz, in oceanic moments of oneness.

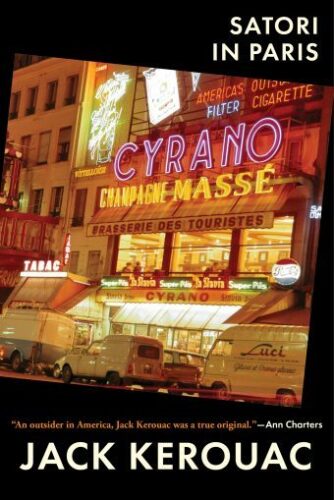

Satori in Paris by Jack Kerouac. Grove Atlantic (2023), 120 pages, $16 (softcover).

70 years after it started, the Beat Movement continues to hold considerable cultural fascination. Nurtured by its origin-story of Columbia University friendships followed by the famed Six Gallery Reading and the San Francisco literary renaissance, amplified by myriad pop representations on TV and in music (Route 66 to Mad Men, Bob Dylan to 10,000 Maniacs), the mystique abides. An inspiration for documentaries, feature films, and high school lit classes, Beatdom has now attained the iconic Full Monty — the centerpiece of academic conferences (where it had been ignored for years).

A tally of artists, literary and otherwise, who can be said to claim some of Beat’s DNA (indistinctly perceived as a mashup of rebellion and beatification) runs to scores, even hundreds. Reduced to its core, however, the essential artists — the OGs — are generally agreed to be Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, and, at the apex, the undisputed Beat alpha, Jack Kerouac.

There have been a score of Kerouac biographies and critical studies, and more are in the works. This was not an inevitability. In his lifetime, his books were dissed, briefly lionized, and then discarded into the ash pit of the forgotten. William Faulkner, more than a dozen novels along in his career, seemed destined to a similar fate. But he lived to see the critical resuscitation of his work and the rise of his reputation. Kerouac’s course runs more akin to that of Poe, Melville, and Fitzgerald, writers who after some early successes labored on in relative obscurity, only later, posthumously, to be elevated to immortality. At the time of Kerouac’s death (at the age of 47) his work was largely out of print. In an uncommon reversal of fortune, beloved by Hollywood screenwriters — a “second act,” Fitzgerald would have called it — Kerouac’s stock has arisen. And his popularity is steady: his back list sells better than most. One can picture him, pugnacious in the afterlife, crowing at his former priest in Lowell, Massachusetts, city of Kerouac’s birth, “I told you I was gonna be a writer.”

A full valuation continues to be made, but it’s clear that Kerouac now occupies a secure niche in the American canon. Since his death, 54 years ago this month, an awareness of — and interest in — his work has continued to expand. At this point, the carping of his contemporary critics — such as Truman Capote’s pissy little remark, “that’s not writing, that’s typing” — comes off as forgettably twee. Incredibly, J. Edgar Hoover’s declaration that “beatniks” were a major moral threat to America was once taken seriously.

Owing to Kerouac’s stature as a cult(ural) icon and reference point, almost any of his 30-some books has its partisans, devotees willing to embrace (and forgive) anything penned by the master. But the truth is that the essential Kerouac can be found in a handful of books: On the Road (1957), The Dharma Bums (’58), The Subterraneans (’58), Dr. Sax (’59), Lonesome Traveler (’60), and Big Sur (’62). Of course, there are partisans for others. George Saunders cites Visions of Gerard (’63) as a favorite.

In honor of Kerouac’s Centenary in 2022, Grove Atlantic launched a series of paperback reissues of some of his work, with eye-catching new covers. The most recent, originally published in 1966, is Satori in Paris, the next-to-last book Kerouac released during his lifetime.

In June of 1965, with money saved from his advance on Desolation Angels (’65), Kerouac flew to Paris with the goal of traveling to Brittany and elsewhere to trace his Franco ancestral roots. It was a whirlwind trip, fraught (as he writes, quoting W.C. Fields) “with eminent peril,” most of the difficulties almost entirely of his own making. There are missed plane and train connections, more or less nonstop boozing, unsuccessful hookups, paranoia, and mind games. Amid all this chaotic drama, there was precious little in the way of genealogical or personal discovery. After 10 days, his money evaporated and energies exhausted, Kerouac abandoned the journey and flew home.

For Kerouac, whose art was always an imaginative transcription of his tumultuous life, it would seem more than enough for a book. The title suggests possibilities: travel, adventure, enlightenment — Beat staples. Unfortunately, the book never quite comes off. Satori is a mixed bag, given Kerouac’s method of rapid composition and his credo of first draft, best draft — don’t mess with what the hand of God had laid down. Written over the course of a week in July of 1965, the book feels slapdash. The spontaneous prose method he had codified in the early ’50s, with its aim of finding “…the wild form that can grow with my wild heart,” supplies only fitful and foundering rewards.

One reason is that Satori lacks the restless energy of his earlier books, On the Road and Lonesome Traveler among them. It doesn’t hunt for the eye-opening epiphanies spotlit in Desolation Angels or supply the raw honesty of the excruciating revelations concerning Kerouac’s alcoholism in Big Sur. And where is the enlightenment? Declared in its title, forecast on page one (sudden illumination, awakening, a “kick in the eye”), alluded to several times en route and reasserted on the final page, the satori, alas, is a no-show.

One reason is that Satori lacks the restless energy of his earlier books, On the Road and Lonesome Traveler among them. It doesn’t hunt for the eye-opening epiphanies spotlit in Desolation Angels or supply the raw honesty of the excruciating revelations concerning Kerouac’s alcoholism in Big Sur. And where is the enlightenment? Declared in its title, forecast on page one (sudden illumination, awakening, a “kick in the eye”), alluded to several times en route and reasserted on the final page, the satori, alas, is a no-show.

Kerouac’s most accomplished books interweave eloquence with a sense of wholeness. This power can be found in such diamond-sharp, emotionally rich scenes as when he leaves New Orleans, or returns home in October, in On The Road, or contemplates life on the Matterhorn in The Dharma Bums, or dreams iodine-scented nightmares in Big Sur.

Hobbling Satori in Paris is its dearth of memorable characters. There is no band of pranksters, no jolly saucy crew (as Dylan might say). Jean Louis Lebris de Kérouac (operating here under his real name because, after all, the book is about his search for family roots) is the star. Everyone is a cameo, a face in the crowd. There is no sidekick, a feature common to classic tales of journey and quest. Absent a Dean Moriarty or Japhy Ryder, a Bull Lee or Cody Pomeray, the solitary trip caters to Keroauc’s melancholy — with no one to pull him out of the dumps, the overall impression is one of self-indulgent sadness.

Kerouac’s best work is often driven by a hunger for spiritual nourishment: the soul food his protagonists occasionally find in friendships, in jazz, in oceanic moments of oneness. Aside from Neal Cassady-inspired characters, the Beat movement was unfairly attacked and slammed in “square” media for its perceived obsession with orgy and drugs. The truth is, a Kerouac protagonist rarely finds fulfillment through sex or chemical means. His characters are beset by an inaccessible loneliness, as poignant as Miles Davis’s horn on Kind of Blue or Sinatra’s voice in September of My Years. Kerouac’s vulnerability in his strongest work — his willingness to take it on the chin, his generosity of spirit, his Christian caritas — are what give him and his protagonists their appeal.

In Satori in Paris his guard is constantly up. He plays the paranoid, the goof, the lout. In one emotionally painful scene he drunkenly goes to his French publisher’s office where, instead of being welcomed (his books, after all, have earned the firm money), he is rudely ignored. Stung, he delivers an imagined putdown of wannabe writers … those who want to imitate the style of young Jack Kerouac at the height of his powers. The moment teeters, interestingly, between self-parody and self-awareness. But too often in this slim book the ever-agonized narrator is more of a verbose pest than a lyrical poet.

Along the way, Kerouac occasionally encounters the kindness of strangers … the cab driver who picks him up in Paris, and a “lovely 40-year-old redhead Spaniard amoureuse who takes an actual liking to me, does worse and takes me seriously, and actually makes a date for us to meet alone.” (He becomes drunk and forgets to keep the date.) More often, though, the characters that show up bounce off each other like billiard balls in a break shot, never sinking into a pocket.

A stronger editorial hand back in 1965 might have addressed these matters, might have teased out the possibilities — at the very least advising that having characters matters because they offer a way into the story. Some readers encountering Satori in Paris, expecting On the Road or Dharma Bums, may feel they’ve been sold a pig in a poke. Others will find a tale that squares with their understandings of the weakness of Kerouac’s art.

In addition to reissues, there have been a string of posthumously published volumes, some dozen or more since 1969. Most are minor writings: late-life lesser books, or juvenilia and apprentice-work, of interest to die-hard fans of Kerouac who are being catered to by literary estates and publishers monetizing their “product.” The best of these posthumous offerings — Visions of Cody (’72) On the Road Scroll Edition (’07), Atop an Underwood (’99), and The Haunted Life (‘14) –are significant, mainly because they illuminate Kerouac’s development as a literary artist. As the reissues roll on, an essential question must be asked: Would this book be of interest if we didn’t know Kerouac?

Author Jack Kerouac. Photo: Wiki Commons

It’s tempting to imagine Satori was written, like On The Road, in scroll-fashion, and then sliced into its short sections. But textual evidence doesn’t suggest this. Each short section moves ahead on its own. Much of the tale is told in present tense. Sentences frequently begin with stale transitionals—“So …” and “Speaking of which ….” — the routine tics that one often sees in an oral narrative. There are effective scenes in Satori, a few comic interludes and sometimes clever word play with French dialects. And at times the prose roils to a breathless momentum, recalling the showering sparks of the lightshow that illuminates the best passages of On The Road and his earlier books. Here the narrator is poking around in an old French archive:

The whole library groaned with the accumulated debris of centuries of recorded folly, as tho you had to record folly in the Old or the New World anyhow, like my closet with its incredible debris of cluttered old letters by the thousands, books, dust, magazines, childhood boxscores, the likes of which when I woke up the other night from a pure sleep, made me groan to think this is what I was doing with my waking hours: burdening myself with junk neither I nor anybody else should really want or will ever remember in Heaven.

A nice irony is that through the ministration of the late John Sampas, Kerouac’s literary executor, this trove is extant, preserved, and scrupulously archived (and some of it sold; Johnny Depp famously paid a five-figure sum for an old Kerouac raincoat).

In another language-fest, Kerouac marvels that

people actually understand what their tongues are babbling. And that eyes do shine to understand, and that responses are made which indicate a soul in all this matter and mess of tongues and teeth, mouths, cities of stone, rain, heat, cold, the whole wooden mess all the way from Neanderthaler grunts to Martian-probe moans of intelligent scientists, nay, all the way from the Johnny Hard ZANG of anteater tongues to the dolorous ‘la notte, ch’i’ passai con tanta pieta’ of Signore Dante in his understood shroud of robe ascending finally to Heaven in the arms of Beatrice.

But the beauty and the bebop snazziness aren’t sustained for long. The Satori‘s drive flags. Kerouac would have been 43 at the time of the European trip and the book’s composition. These should have been productive years, but he was wearing thin psychologically and aging out artistically. Years of alcohol abuse had exacted a toll. (The possibility of CTE has been raised as well; Kerouac was a serious athlete in his youth.) Politically, the rebel had descended into a cranky middle-age beset with reactionary twitches; his outlook was now patently at odds with such progressive confreres as Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gary Snyder, and Michael McClure.

All of this said, Sartori meets an ever-expanding interest in Kerouac’s work and life, an enthusiasm that unites scholars as well as the reading public. In reissuing some of them to meet this appetite, the Kerouac Estate and Grove Press deserve kudos.

Kerouac’s work is now part of the canon. As Grove’s series of reissues proceeds, it would benefit from the addition of commentary. At the very least, detail about the books’ composition and construction would shed valuable light on the writer’s methods and his working relationship with his editors. At this point, there is no question Kerouac’s fiction will attract attention for a long time to come. Deepening our understanding of his art would seem to be a vital part of honoring that legacy.

David Daniel has been the Jack Kerouac Visiting Writer in Residence at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell. His newest book, a collection of stories, is Beach Town (2023 Loom Press).

He, Dave Daniel, sure knows how to write. This bleaker picture of Kerouac hits the spot.

An insightful review from a Kerouac scholar. Thanks, David Daniel!