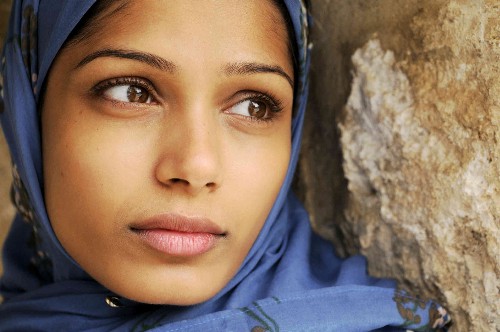

Fuse Film Review: Julian Schnabel’s “Miral” — Emotion, Beauty, Power and ‘Huh’

For a film in which politics are of such moment, “Miral” longs to be apolitical—or just sublimely fuzzy.

By Harvey Blume.

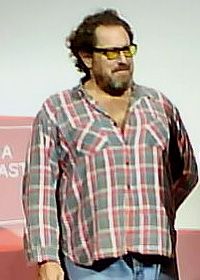

I saw Miral today, the Julian Schnabel film that’s caused a ruckus. It’s powerful and good-looking. Schnabel brings a painter’s eye to the Mideast, a love of scenery and light, and fine, maturing, cinematic instincts. He also brings flaws that seem almost intrinsic to film when it brushes up against historical complexity. Later, just a bit removed from the emotions Miral aroused, I found myself bubbling up with reservations.

The film mutters a bit much. I mean that literally. You can barely hear what the Palestinian characters are saying as they argue about politics. These arguments, insofar as they are audible, are of import. Should Palestinians, in the late 1980s, during the first intifada, consider negotiating with Israel? Should they entertain the prospect of accepting a state of their own on the West Bank and in Gaza? Or should they go on fighting for the very abolition of the Jewish State?

To these weighty questions, the answer is in large part mumble mutter mumble.

One of the characters gets throttled on suspicion of having treasonously named names to Israeli intelligence. But that happens mumble-wise too, in cinematic terms, which is to say, pretty much off-screen. (He’s dragged off. His legs twitch.)

For a film in which politics are of such moment, Miral longs to be apolitical—or sublimely fuzzy. Schnabel wanted to make something warmhearted, beautiful, and decent, something that would give you a hint of how history—roughly from Partition to the Oslo accords—looked from the Palestinian side, and he has succeeded—if you don’t mind a good deal of dangling narrative and some outright absurdity.

Near the beginning of the film, for example, you see a gaggle of Palestinian kids on a street in Jerusalem. It’s 1948, and the dirty, disheveled kids explain they are from Deir Yassin and from one to the other fill you in rapid-fire on the details of the horrible massacre that village in fact endured—and they escaped. But escaped how? Why were they spared? How did they get to Jerusalem? If that’s covered, I missed it.

Schnabel is not making a documentary and doesn’t have to dwell inordinately on such detail. But in too many cases he refuses to even consider connecting any dots. Connecting is just not his thing. Thus, along with the emotion, beauty, and power of Miral, there’s a lot of plain old “Huh!?”

As another example, William Dafoe plays an American army officer stationed (for no known reason) in Jerusalem right as the United Nations votes to partition Palestine, and war is breaking out. Dafoe puts a lot of energy into the part—he seems maniacally sympathetic to all concerned, as if his smile was having an Intifada of its own—and you therefore expect that this kinetic individual will have some impact on the plot. Nope. Dafoe just disappears. So what was the point? What was Schnabel thinking? How nice it would be to shoot a bit of Dafoe looking lean, fit, and not completely crazed in an army uniform?

The same sort of “huh?” applies to an opening scene, in which we get an even briefer bit of Vanessa Redgrave, sweetly—dare I say it, geriatrically?—doddering, in an overgrown, laurel wreath as, in a posh, Jerusalem hotel, she welcomes all concerned to share with her the holiday of Christmas—Christmas in Jerusalem—beneath a tree that she assures her guests—Palestinians, American Jews (and, again, for no apparent reason, the dashing Dafoe)—will be reinserted into the soil when the holiday ends?

How very nice.

There was a war going on outside. That might be one reason, among others, that there were no standard issue Israelis welcoming in the, um, Christmas spirit.

Look, I don’t want to dismiss this film. It had me close to sobbing at times, as it sped from the horror of Deir Yassin to the hopes held out by the Oslo Accords. The acting is good, likewise, as stated, the cinematography. And Miral ends with a dedication to all those who still believe in the possibility of peace. Though this possibility may be diminishing, I am in that camp.

Schnabel has been damned by some critics for making a political film that takes the Palestinian side. I would disagree. I don’t think he’s made much of a political film at all. He dials the volume down on politics to the point of nearly muting them, and turns his camera on hills, beaches, water, and fine faces. What you get is less a movie than a painting.