Poetry Review: Ann Lauterbach’s “Door” — Opening the Doors of Perception

By Norman Weinstein

Poet Ann Lauterbach’s 11th book contains a challenging invitation: poems that offer fresh perceptions of life’s beautiful enigmas.

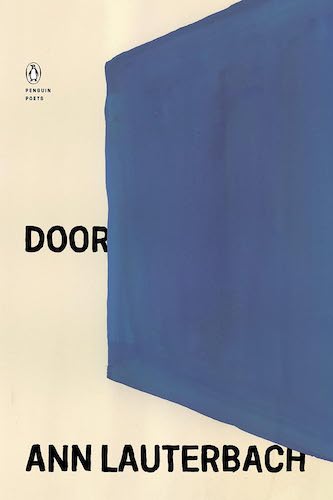

Door by Ann Lauterbach. Penguin Books, 94 pages, $20.

If you think that Door is a curiously odd title for a book of poems, a title more apt for a mystery novel, think again. “I see the poem or the novel ending with an open door,” writes the Canadian author Michael Ondaatje, who excels in both. “I have always knocked at the door of that wonderful and terrible enigma which is life,” wrote the Nobel Prize-winning Italian poet Eugenio Montale. And this connection between symbolic doors and poems was heralded by two major 19th-century American poets. “Not knowing when the dawn will come, I open every door,” wrote Emily Dickinson, and “Be an opener of doors for such as come after you,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson.

If you think that Door is a curiously odd title for a book of poems, a title more apt for a mystery novel, think again. “I see the poem or the novel ending with an open door,” writes the Canadian author Michael Ondaatje, who excels in both. “I have always knocked at the door of that wonderful and terrible enigma which is life,” wrote the Nobel Prize-winning Italian poet Eugenio Montale. And this connection between symbolic doors and poems was heralded by two major 19th-century American poets. “Not knowing when the dawn will come, I open every door,” wrote Emily Dickinson, and “Be an opener of doors for such as come after you,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson.

I welcome you to the latest poetry book by Ann Lauterbach. These door reveries from Ondaatje, Montale, Dickinson, and Emerson resonate with the heart of the 44 poems comprising Lauterbach’s Door. Put simply: Lauterbach is a poet for whom daily life teems with open-ended enigmas, wonderful and terrible mysteries which even the most exquisitely crafted poetic language (which Lauterbach fashions) can only suggest indirectly. Yet her poems do considerably more than simply insinuate life’s unanswerable questions. With stunning emotional force and intellectual power, Lauterbach compels us to question our everyday assumptions about what is most beautiful and true in our lives. Here is an example from a poem entitled “Interiors” — and note how often Lauterbach’s titles favor architectural terms:

I have turned my back on the mountains. Let the sun have them.

Let the sun have the river as well, I am done with it.

I am done with the sun and the mountains and the river.

Now I will stare at the spines of books.

At the spines, and the hinges, and the knobs.

The spines of books hold a chorus

Singing from the dead to the living,

And from the living back to the dead.

This poem displays several features evident throughout Lauterbach’s Door. Notice how “The Interior” moves from an opening vista of the natural world (oddly dismissive) to the vantage of a home library. The image of book spines morphs into the surreal with suggestion of a door (“and the hinges, and the knobs”). We end up with an assertion that reading brings a commingling of the living and dead. This underscores “Interiors” as a dreamy sequence of digressions. Lauterbach’s poem zigzags from this claim to a philosophical reflection on the adequacy of poetic language to reflect a daily reality that is in constant flux:

I was speaking to a young man about

The ineffable. He seemed to want to find a way

To say it. I said the nature of

The ineffable is the unsayable.

At this point in the poem Lauterbach turns to paradox, giving a voice to the ineffable, a magical act that her chief influence, poet John Ashbery, did so exquisitely. At the conclusion of “Interior,” Lauterbach claims that “Questions burden us…”.” But she often poses unanswerable questions in her verse, reminding us that burdensome questions can be poetic opportunities in disguise, catalysts for stretching our imaginations.

The picture I have presented thus far of Lauterbach’s poetry might discourage readers who favor verse in which the poet straightforwardly confesses his or her stressed personal life, a fashionable psychological stance popularized by poets who foreground their complex racial and sexual identities. While poetry in that vein has its place, and should be appreciated, revelations of personal sorrow and grief can have as much — if not more — emotional resonance when presented obliquely. Many of her poems of this type see the door as a symbol that separates life from death, intimations of mortality no doubt propelled by memories of the unexpected early deaths of her father and sister. Here is a taste of the elegiac tone of Lauterbach’s poem entitled “Door,” one of eight poems with “door” in their title in this book:

Marauding ravenous jays

Wearing the uniform of the sky

Plummet downward onto stones.

My father is a blue jay, dead on an attic floor

Yet Lauterbach’s door poems also open out to supply whimsical delight. She began her artistic journey with a desire to become a painter in New York decades ago. The play of color in her poems reflects her continued passion for painting, as do poems inspired by Giotto, Delacroix, and Magritte:

I don’t know who lives in these houses

With pastel doors, mint green

And pale salmon. Whoever heard of a lavender

door in the middle of winter, as if

snow could dilute

alizarin crimson, saturated lapis,

deepest cobalt blue.

Does the term “alizarin crimson” puzzle? It did me, so I researched this paint. Look at a color wheel: “alizarin red” is a red that is closer to a purplish-blue than it is to an orange. Perhaps it is the color most associated with red doors at the front of homes and commercial buildings. It seems to match the color of American painter Kenneth Noland’s painting on a wooden door panel entitled “Parisian Bar,” one in his series entitled “Doors” (1987-89). This said, the exotic sound of “alizarin” may have also smitten Lauterbach. And notice how her vision of a house door, as vibrant as a painter’s palette, leads readers on a journey where the everyday becomes marvelous.

Lauterbach’s Door encourages us to think more flexibly and sensitively about the exotic curiosities that circulate beneath the prosaic. “Look now. It will never be more fascinating,” advised the poet and art critic James Schuyler. Lauterbach’s urgency in these poems is at the service of expanding where we find the fantastic, of encouraging readers to look to the ordinary for their enchantments.

Norman Weinstein is a poet, translator, and critic. His books include A Night in Tunisia: Imaginings of Africa in Jazz and No Wrong Notes, a book of prose poetry. He can be reached at nweinstein25@gmail.com.