Film Festival Reviews: TIFF 2023 — Corruption and Cops

By David D’Arcy

Reviews of three films at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival that draw connections between class, violence, and politics.

A scene from Ryoo Seung-wan’s Smugglers. Photo: TIFF

One of the revelations of this year’s Toronto International Film Festival (through September 16) is Smugglers, directed by Ryoo Seung-wan. The story is set in South Korea in the ’70s, with plenty of action and some of the worst clothes that you’ve seen in a long time. Centering on women swimmers harvesting shellfish illegally, the plot offers an undersea crescendo that makes Thunderball’s legendary battle look like ripples in a rain puddle. As for the costumes, they out-kitsch those of Silver Linings Playbook.

All of this is good entertainment, but Smugglers also gives you a close look at exploitation from a number of perspectives, most notably the point of view of the swimmers, who are pawns in a fight for profit over a resource threatened by pollution and crime. The result is bloody, and hilarious. No surprise, these women curse like sailors.

On a boat where haeyon (women swimmers) dive for seafood as they have for generations, the captain and male crew are practiced at outracing police and customs officials. We watch the haeyon stuff their ill-gotten cash into new clothes. Think disco fashion with hair to match on men and women.

Soon enough, law enforcement wants its share of the lucrative racket. The women end up going to prison — where they make wigs. Once they’re out, they’re swimming again, but the police and mobsters have targeted them for elimination. Imagine a subterranean battle between women swimming in traditionally modest work garb fighting armed men in scuba gear. There’s enough blood to attract sharks. Yes, there are real sharks in the script.

In between explosions of violence and comic craziness, this action slugfest has lessons to teach. We learn that the graceful craft of the haeyon was slowly disappearing in the ’70s. (An exploitation film would have shown the women wearing less clothing — Smugglers doesn’t.) And we see that the waste from a chemical plant on a shore nearby is eliminating sea life with impunity. No surprise, the supposed enforcers of the law are cashing in on the illegal trade, even as pollution is making it inedible.

Be prepared, if you’re fortunate enough to see Smugglers, for a film that has its overlong stretches. Korean fans, nothing if not passionate, obviously enjoy seeing their stars dressed up like dancin’ fools, or like anything different. They’ll tolerate shtick more than non-Korean Americans or Canadians will.

Director Ryoo Seung-wan is adept at making the unbelievable in real life seem plausible. His previous film, Escape from Mogadishu, focused on how South Korean and North Korean diplomats teamed up in an effort to flee war-torn Somalia as the government was being overthrown. Diplomats from both countries had been lobbying African countries, such as Somalia, for their votes in the United Nations, at a time when neither Korea was a member state. They ended up in the line of fire and then some. I wonder if the North Koreans in Somalia then are out of Kim’s prisons yet. Escape from Mogadishu was the most popular South Korean film of 2020.

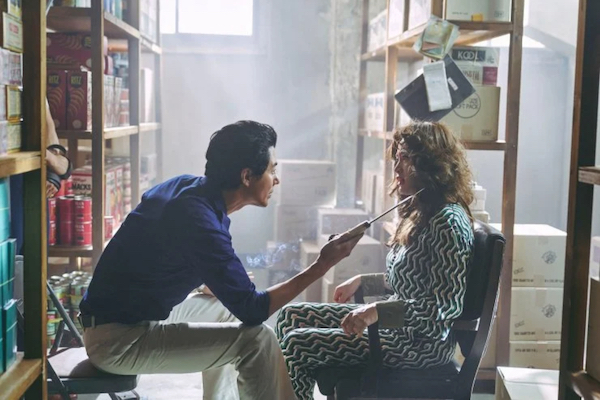

Nowolo Dlamini in Death of a Whistleblower. Photo: TIFF

From South Africa, Death of a Whistleblower, directed by Ian Gibson, is a pulp thriller, like Smugglers, yet farther to the left politically. The action begins in 1985 with a white couple quarreling on a military base. A young woman flees on foot, with her soldier boyfriend in pursuit. She eventually passes through barbed wire into an enclosure where her eyes begin to bleed and her skin reddens. Men in Haz-Mat suits seize her and hose her down before she dies.

The narrative leaps to the present, where an editor scolds a Black woman journalist Luyanda Masinda (Nowolo Dlamini, 2022’s Silverton Siege) for reporting what she’s learned about the activities of private security companies, a euphemism for mercenaries. We see that an informer from inside South African intelligence has given documents to another reporter, who’s now a target of white thugs who are getting rich advising African dictators on how to subjugate their own citizens — a business in which South Africans have experience. Before Luyanda decides whether she wants to do anything more than to sleep with the reporter, he’s killed by hit men.

With the help of a tech-savvy friend (Kathleen Stephens), Luyanda follows a trail initiated by the discovery of secret chemical weapons. That leads to locating former South African spies who are training the troops of the brutal African regimes. Spasms of violence accompany the journalist’s revelations, along with proof that government officials are involved. The challenge for Luyanda: to get the criminals before they get her and her friends. The body count piles up.

At the beginning, Death of a Whistleblower telegraphs its punches via awkward scene-setting dialogue, yet the proceedings become increasingly urgent once Dlamini appears. She is an actress to watch: her journo heroine is a confident and charismatic wisecracker.

Gibson’s grim political message is that the Truth and Reconciliation Commissions, which were meant to bring national justice and healing, ended up cleansing major criminals of the stain of apartheid. The underworld now supports “legitimate” firms that keep African tyrants in power.

A scene from The Undesirables (Building 5). Photo: TIFF

Speaking of the realm, or genre, of ungovernability, The Undesirables (Building 5) is a hyper-charged example. Directed by Ladj Ly, the film rarely takes a breath: the camera is continually lurching ahead to keep up with the fierce action. The setting is a decaying public apartment building in a French suburb, populated by mostly Arab and Black African residents, all of whom are too poor to find anywhere else to live.

The mayor of the town suddenly dies, and a local white doctor (Alexis Manenti) takes over the office. He’s short and resembles French president Emmanuel Macron. If the guy ever meant well, he’s gotten over it. He also seems to have the only respectable house in the town, and his political mission is to bring in more people who can afford to live that way.

The doc does more than tolerate police brutality — he encourages it. Haby (Anta Diaw), a young African woman, assembles a crowd to announce that she’s running for mayor. His response is to send in the police to evict her, her family, and everyone else from their building.

The residents refuse to leave and somehow a fire starts. They flee, but not before they hurl their belongings from the windows, as if they were abandoning ship. Ladj Ly brings a staggeringly graceful visual poetry to the scene: family homes are being emptied while those homes are being destroyed. Trucks wait patiently outside to cart the families’ property off to garbage dumps. (The fire department is off that night?) Cops teargas those who try to stop what’s happening. Is it any wonder the youth in these families become radicalized?

Ladj Ly won the top prize at Cannes for 2017’s Les Miserables (Arts Fuse review), a kinetic drama about local citizens’ movements that are fighting for safe low-income housing and protesting police brutality. That film ended with Arab and Black protesters standing tall, singing confidently. In The Undesirables, Ly has become less optimistic; the violence from the underclass has only increased since then because lessons have not been learned. Ly can’t end his film effectively. His subject won’t let him.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: Death of a Whistleblower, Ian Gibson, Ladj Ly, Nowolo Dlamini, Ryoo Seung-wan, Smugglers, The Toronto International Film Festival, The Toronto International Film Festival 2023