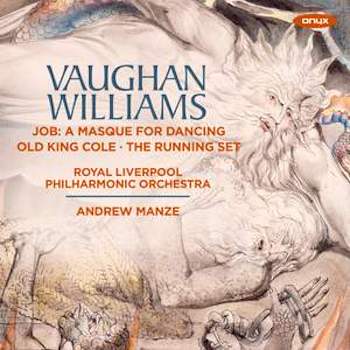

Classical Album Review: Andrew Manze Conducts Vaughan Williams

By Jonathan Blumhofer

The album is a welcome appendix to the conductor’s admirable symphonic cycle with this orchestra, as well as a timely reminder of Vaughan Williams’s compositional range.

Andrew Manze may be done with his recorded cycle of Ralph Vaughan Williams’s nine symphonies, but that doesn’t mean he’s finished surveying the composer’s larger orchestral output. Given the triptych we’ve got here, that’s a good thing.

Andrew Manze may be done with his recorded cycle of Ralph Vaughan Williams’s nine symphonies, but that doesn’t mean he’s finished surveying the composer’s larger orchestral output. Given the triptych we’ve got here, that’s a good thing.

Again, Manze teams up with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra (RLPO), this time for a set of three pieces Vaughan Williams wrote for the dance: Job, Old King Cole, and The Running Set.

The latter is the shortest entry, though its incorporation of four English folk tunes lacks nothing for bumptiousness and character. Indeed, it’s hard to explain why or how this devastating charmer has passed under the radar for so long (Vaughan Williams wrote The Running Set in 1933 for the following year’s National Folk Dance Festival). Suffice it to say, Manze and Friends make invigorating work of its six-minute duration.

They’re similarly persuasive in Old King Cole, a larger folk-inspired ballet, which was written in 1923 for a performance in Cambridge. Running about 20 minutes, it’s a slight piece but nevertheless well crafted and full of ear-catching touches (including a series of lovely violin solos that are here winningly dispatched by Eva Thorarinsdottir).

Throughout, Manze draws playing of biting rhythmic precision from the RLPO, as well as textural clarity: the “Pipe Dance” is graceful and delicate while the “Slow Dance” unfolds with diaphanous wonder. There’s also more than a little fantastic low brass playing to be heard across the performance, too, nowhere more impressive than in the jaunty “General Dance.”

Though Job is by far the most familiar piece on this album, it suffers a bit by comparison to its companions. Vaughan Williams’s 1931 “masque for dancing” relies rather too heavily on repetition, which means — among other things — that, sans choreography, the composer’s pastoral idiom can drag. This tendency isn’t helped by a penchant for sleepy tempos.

That said, Manze and the RLPO imbue the score with all the qualities found in Old King Cole and The Running Set. When it can, the performance snaps. The orchestra’s playing is exceedingly well balanced and matched: the dovetailing of lines in the “Dance of Job’s Sons and Daughters” is exquisite. So are the violin and clarinet solos in “Elihu’s Dance of Youth and Beauty.”

There’s no shortage of personality in this interpretation, either. From the invigorating “Dances of Plague, Pestilence, Famine, and Battle” to the plaintive woodwind cortege in “The Dance of the Three Messengers” and the furious vision of Satan’s enthronement, Manze’s is an interpretation that blazes — and with purpose.

Taken together, it’s a welcome appendix to the conductor’s admirable symphonic cycle with this orchestra, as well as a timely reminder of Vaughan Williams’s compositional range.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Once again, thanks for the insightful and extremely helpful review of Vaughan Williams.