Film Commentary: Scorsese and Cinema — Before and After “After Hours”

By Peter Keough

This shaggy dog story, set in the bowels of Manhattan, in the yet to be gentrified bohemian enclave of SoHo, presented an opportunity for Martin Scorsese to return to the kind of bare-bones filmmaking that produced such acclaimed masterpieces as Mean Streets and Taxi Driver.

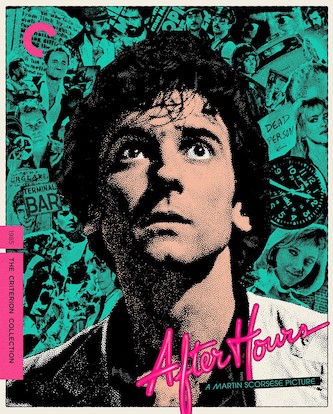

Had Martin Scorsese not been slipped the script for After Hours (1985), his liminal, Limbo-like excursion into Kafkaesque absurdity, after the disastrous critical reception and box office failure of his brilliant The King of Comedy (1983), we might never had a chance to see his heralded, upcoming Killers of the Flower Moon or the two dozen or so features in between. That’s among the insights shared in an interview with the director, one of the extras included in the superb Criterion Collection Blu-ray re-release of the film.

The studio had pulled the plug on his dream project, The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), and Scorsese feared that his career was over. He was sure at the very least that he would never be allowed to make a big budget film again. But this shaggy dog story, set in the bowels of Manhattan in the yet to be gentrified bohemian enclave of SoHo, gave him an opportunity to return to the kind of bare-bones filmmaking that produced such acclaimed masterpieces as Mean Streets (1973) and Taxi Driver (1976).

More importantly, the screenplay — written by Joseph Minion whose other claim to fame might be writing 1988’s Vampire’s Kiss, a masterpiece of a different kind — resonated with Scorsese’s own feelings of abandonment, Catholic guilt, desolation, persecution, and the inexorability of an absurd universe. It opens in an office with Paul Hackett (Griffin Dunne, who also produced the film), depressed and muted in a taupe (a dominant, suffocating hue in the film’s desolate palette) Brooks Brothers suit, instructing Lloyd (Bronson Pinchot), a new employee, in how to operate a word processor. When Lloyd confesses that his work there is just temporary, that he has big plans in publishing and wants to start up his own magazine, Paul zones out, perhaps knowing that Lloyd’s dreams are delusional. Maybe because he has had such dreams himself.

Some have observed that Paul’s misadventures would not be likely to happen today in the age of cell phones, Ubers, and the other dubious benefits of four decades of consumerism and technological innovation. Ironically, though, his attempt to escape an early version of this computerized future is what initiates his odyssey.

Later that night he sits in a coffee shop reading Henry Miller’s much-banned 1934 novel Tropic of Cancer (which opens with the words, “I am living at the Villa Borghese. There is not a crumb of dirt anywhere, nor a chair misplaced. We are all alone here and we are dead”). The book catches the eye of Marcy (Rosanna Arquette), a winsome young woman at the next table. “‘This is a prolonged insult, a gob of spit in the face of Art,’” she says, reciting Miller’s description of the book, “‘a kick in the pants to God, Man….’”

She is Paul’s kind of a woman, if Paul were the kind of man to have that kind of woman.

But then, a big break. Marcy mentions that she lives with Kiki (Linda Fiorentino), an artist with a studio downtown in SoHo who makes paperweights out of plaster of Paris in the shape of bagels and cream cheese. Would Paul be interested in buying one? He is, and as he tries to write down Kiki’s phone number in his book, his pen skips. He tries again; it works. It is a warning, unheeded, and the first of recurring, dreamlike obstructions encountered in his struggle to fulfill his desire, his failures to do so, and his attempts to escape the consequences.

Later, after he has called the number, made contact, and arranged to meet Marcy at Kiki’s place, he catches a ride on the taxi from — or maybe to — hell. The driver, the first of several allusions to classical mythology and a clear nod to Scorsese’s previous films, zooms off maniacally. Paul’s proffered $20 bill, all of his cash, blows out the window. When he explains the situation to the driver, the guy speeds away without a word. So Paul gets off easy, this time.

Paul next dodges a potentially lethal set of keys dropped from the window of Kiki’s loft. ( In the commentary, Scorsese and the cinematographer Michael Ballhaus relate how Dunne was almost killed for real when the camera they jury-rigged with a bungee cord to record the shot almost hit him.) Inside, the cool, alluring, be-bra-ed, and indifferent Kiki works on her latest opus, a life-size papier-mâché sculpture of a person in agony. It resembles the figures immortalized in ash in the ruins of Pompeii, or, as Paul points out, Edvard Munch’s The Scream (he calls it, The Shriek; Kiki coldly corrects him). Later, he will note that the surface of the sculpture is plastered with twenties; a temptation, for the moment, resisted.

Griffin Dunne in After Hours.

Alarmed and intrigued by Kiki’s demeanor, artwork, and the cryptic squalor of the decor, Paul remains undaunted. But things don’t go well with Marcy. Oddly, Paul’s uncharacteristically churlish behavior is to blame. He samples Marcy’s pot and turns nasty. He calls her a liar, insists that she show him the paperweights he came there to see and, when she leaves to get them, he bolts and escapes into the rainy night.

In a film full of mind-boggling twists and turns this one inordinately puzzles me. Was it Marcy’s tales of being raped by her boyfriend that sparked Paul’s nasty petulance? Or could it be that pictures in a book about burn victims triggered his memories of being blindfolded as a child in the burn unit of a hospital? Maybe it was the dope. As Nancy Reagan would say in the anti-drug campaign she kicked off around the time the film was made, maybe he should have just said no.

Be that as it may, Paul now has the will to leave SoHo and its weird and perilous temptations behind. But not the means. He has some pocket change, but not enough because the subway fare had just increased at midnight. The attendant at the station, one of the intransigent gatekeepers à la Franz Kafka’s The Trial and The Castle (a later Kafkaesque allusion, painfully apt, will be to “In the Penal Colony”) he will meet in the course of the night, won’t let him through.

So the ordeal continues. After his failure with Marcy, he will encounter three other women (played with perverse, sinister, and bemused hilarity by Teri Garr, Catherine O’Hara, and Verna Bloom), each of whom will offer him a sphinxlike challenge, which he will meet with varying degrees of success. In the end [spoiler!] he achieves a kind of redemption, a rebirth — though back into the limbo-like existence he had originally tried to escape.

But for Scorsese, redemption was unambiguous. Though the critical response to the film was mixed (in the commentary, Dunne bemoans the fact that Pauline Kael, a critic he idolized, described his performance as that of “a second-rate Dudley Moore”), Scorsese would win the Best Director prize at Cannes. A big studio movie would follow — the aptly titled The Color of Money (1986) — and then his dream project, The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), though it could be argued that Scorsese had crossed this Via Dolorosa already with After Hours.

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He had been the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, most recently For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

Good review.

Who was cuter than Rosanna Arquette? Loved her in Life Lessons in New York Stories.

There are lots of nods to Freemasonry in the film and the final scenes are based on the first three inhiation rituals to become a Freemason. There is also a lot of references to Operation Paperclip and CIA covert programs.

Llloyd’s comment about wanting to run a literary magazine isn’t a sign of delusion it’s a sign that they work for the CIA. That’s also why Paul has knowledge of Colombian drugs.

https://medium.com/bomb-magazine/uncovering-the-cias-covert-funding-of-american-literary-journals-4a0ec9782567

The final dialogue of the film between Cheech and Chong’s characters is a seemingly unimportant rant where Cheech mixes up the actor George Segal with the sculptor of the same name. This is Scorsese and Minion telling the viewer that everything in the film is loaded with multiple meanings.