Book Review: “Heretical Aesthetics: Pasolini on Painting” — Demanding the Miraculous

By Peter Walsh

It is the volume’s autobiographical component, the accounts of Pasolini’s wide wanderings in art and aesthetic revelations, with their dramatic, cinematic flashbacks, that give this collection much of its literary value.

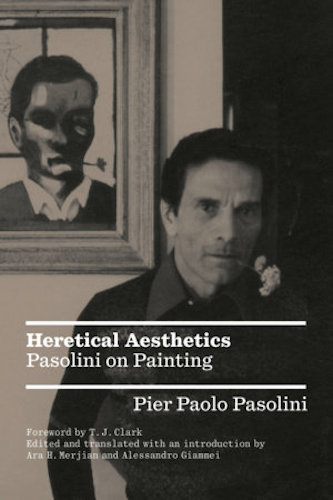

Heretical Aesthetics: Pasolini on Painting by Pier Paolo Pasolini. Preface by T.J. Clark. Edited by Alessandro Giammei and Ara H Merjian. Verso, 224 pages, $24.95.

Pier Paolo Pasonlini is best remembered in the United States for his radical films, his Marxism, his open homosexuality, and his horrific 1975 murder (Pasonlini was beaten, deliberately run over multiple times, and set on fire). In life, though, he was one of the leading public intellectuals in postwar Italy: filmmaker, essayist, art critic, poet, journalist, painter, novelist, playwright, actor, translator, lecturer, media personality, and [breath] left-wing activist. Ara H. Merjian and Alessandro Giammei, editors and translators of Heretical Aesthetics: Pasolini on Painting, point out that his published complete works in Italian, which exclude his diaries and extensive correspondence, fill 10 “densely printed” volumes: some 20,000 pages, which means that over the course of his relatively short life he “must have written thousands of words every day, without fail.” The depth and extent of Pasolini’s influence over late 20th-century Italian culture is equally hard to grasp. Merjian and Giammei quote translator Ben Lawton: “If Norman Mailer, Truman Capote, Gore Vidal, Camille Paglia, Madonna, Martin Scorsese, Spike Lee, Michael Moore, and Noam Chomsky were rolled up into a single person, one might begin to get some idea of the impact Pasolini had on Italian society.”

Pier Paolo Pasonlini is best remembered in the United States for his radical films, his Marxism, his open homosexuality, and his horrific 1975 murder (Pasonlini was beaten, deliberately run over multiple times, and set on fire). In life, though, he was one of the leading public intellectuals in postwar Italy: filmmaker, essayist, art critic, poet, journalist, painter, novelist, playwright, actor, translator, lecturer, media personality, and [breath] left-wing activist. Ara H. Merjian and Alessandro Giammei, editors and translators of Heretical Aesthetics: Pasolini on Painting, point out that his published complete works in Italian, which exclude his diaries and extensive correspondence, fill 10 “densely printed” volumes: some 20,000 pages, which means that over the course of his relatively short life he “must have written thousands of words every day, without fail.” The depth and extent of Pasolini’s influence over late 20th-century Italian culture is equally hard to grasp. Merjian and Giammei quote translator Ben Lawton: “If Norman Mailer, Truman Capote, Gore Vidal, Camille Paglia, Madonna, Martin Scorsese, Spike Lee, Michael Moore, and Noam Chomsky were rolled up into a single person, one might begin to get some idea of the impact Pasolini had on Italian society.”

The title Heretical Aesthetics references a 1972 collection of Pasolini essays: Heretical Empiricism (Empirismo eretico); the adjective there suggested the author practiced an unorthodox, heretical kind of Marxism. But in the context of mid-century painting, the word could also be taken as a heresy from American critical orthodoxy, as established by the country’s then-dominant art critic, Clement Greenberg. His theory was that Western painting evolved toward Platonic abstraction and flatness, slowly squeezing out the illusion of space and objects in a real world.

To Pasolini (among others), this abstraction was a part of what he perceived, say the book’s editors, “as the homogenizing and leveling culture of neocapitalism,” that drained art of specificity, of all kinds of social content or class consciousness. Abstract art works repeatedly surface in Pasolini films as “both a sign and symptom of a specious autonomy — a pathetic gesture of revolt masking a (by now) inexorable conformism.” This forced conformity Pasonlini saw through the lens of the standardization of the Italian language, a standardization that, under Fascism, became “coercive and repressive,” an infection of the bland and passive that morphed into postwar consumerism: “Bourgeois culture, he announced in every possible forum, was an illness with which all of Italy had been fatally infected.”

This virus Pasolini countered with “various interpretations of localized, marginalized dialects and idiolects.” For example, there were the dialects of his native north Italian region of Friulia, a north Italian region, or the language of the Roman demimonde that he used in novels of the ’50s, which he also “extended into the visual.” In this he tried to give voice and visibility to those that the dominant culture ignored or attempted to paint out of the picture. He even founded an academy to help preserve Friulian language.

Many of the pieces in Heretical Aesthetics are short, written for newspapers or literary and art journals (one of them co-founded by Pasolini himself), to accompany exhibitions, or found as unpublished fragments. Some of them are written partly, or even entirely, in verse. This is not to say they are necessarily quick reads. First of all, there is the language. Of an early 1947 essay, Pasolini’s translators note, “the piece’s convoluted prose bears witness both to the ambition of a budding critic and to the perceived prerequisite of any young Italian intellectual: a facility with subordinate, Latinate clauses.” And he has trouble sticking to his points: “Even in their brevity, [these essays] submit glancing impressions to Pasolini’s characteristically involuted, almost helicoidal prose. A prose that — like the poetic, pictorial, and cinematic oeuvre of which it is an extension and reflection — replenishes itself by willfully ‘contaminating’ its intellectual tributaries flowing out from formal and technical reflections, dipping now into semiotics and structuralism, swelling into lyrical excursus, settling into thinly veiled autobiographical allusion.”

Roberto Longhi — considered by many to be Italy’s greatest art historian. Photo: Wiki Common

On top of this there’s the faded historical context. Pasolini often discusses artists or writers, some of them lifelong friends, who are now little remembered (almost all traces of at least two of them have disappeared), or he debates issues in contemporary Italian culture or politics not much appreciated outside of Italy, even at the time. Here, Martian and Giammei’s heroic editing comes to the rescue. At least a third of this anthology of Pasolini essays on painting is written by its editors: in their long introductory essay, “A Force of the Past,” and in their brief commentaries that follow each and every piece. Thanks to these glosses, the reader learns what Pasolini meant by “contamination” in art, who Virgilio Guzzi was, and why the Fascist Party’s Foglio di Disposizione could easily have caused problems for Pasolini’s wartime writing.

One truly famous name: Roberto Longhi, appears regularly in these essays. Longhi, considered by many to be Italy’s greatest art historian, is best known for his “rediscovery” of the now-classic Italian painters Piero Della Francesca and Caravaggio. Both artists had been half forgotten and largely overlooked by modern scholars. Longhi was able to show, for example, how Caravaggio’s use of dramatic “chiaroscuro” lighting and models taken from the streets (rather than following classical examples) to represent saints and members of the Holy Family spread throughout 17th-century Europe, reaching as far north as Rembrandt in the Netherlands. Pasolini studied under Longhi at Bologna in the early years of the war and revered his teachings ever after, referring to the older man as his “maestro.”

Longhi’s interpretations of both Della Francesca and Caravaggio, along with other Italian masters such as Mantegna, had an enormous influence on Pasolini’s writing and films, though Pasolini always argued that the influence was not simply formal or compositional. In “Venting About Mama Roma” (1962), he rails against critical interpretations of his recent films. He says that, in a recent interview and article, he had explained “my figurative vision of reality derived from pictorial (rather than cinematographic) origins, and that this shed light on certain phenomena, particularly my mode of shooting. I explained, in short, that my films’ pictorial references formed a stylistic penchant and not, blast it, mere re-creations of particular paintings!”

“[Carravaggio] realized that there were individuals around him who had never appeared in the great altarpieces and frescoes,” Pasolini writes in “Caravaggio’s Light” (1974), “individuals who had been marginalized by the cultural ideology of the previous two centuries. And there were hours of the day — transient, yet unequivocal in their lighting — which had never been reproduced, and were pushed so far from habit that they had become scandalous, and therefore repressed.” These elements Pasolini translated into cinema.

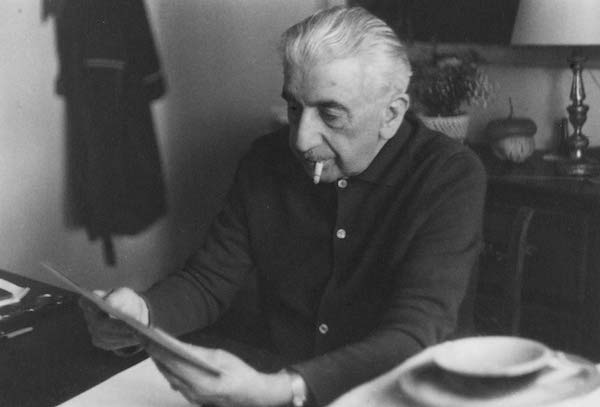

Pier Paolo Pasolini in 1964. Photo: Wiki Common

In their introductory essay, Merjian and Giammei claim that “[w]hether implicitly or explicitly, subtly or unabashedly, all [Pasolini’s] writings on painting prove self-referential to one degree or another.” It is this autobiographical component, the accounts of Pasolini’s wide wanderings in art and aesthetic revelations, with their dramatic, cinematic flashbacks, that give this collection much of its literary value.

“Thinking back to that small classroom with very tall desks and a screen behind the lecturn,” Pasolini recalled in “Roberto Longhi’s From Cimabue to Morandi” (1974), “where I attended Roberto Longhi’s courses at the university of Bologna over the academic year 1938-1939 (or was it ’39-’40?), I feel like I am thinking of a desert island in the heart of a lightless night.… Back then, in the wartime winter of Bologna, he was simply the Revelation…. Slides were projected on the screen: full-scale reproductions and details from the works of Masolino and Masaccio, painted in the same places at the same time. Cinema acted there…. It acted when a ‘shot’ representing a sample of Masolino’s world was dramatically ‘countered’ — with the continuity that is typical of cinema — by a ‘shot’ representing, in turn, a sample of Masaccio’s world…. The fragment of a formal world was physically, materially, placed in a montaged sequence with the fragment of another formal world: one ‘form’ with another ‘form.’”

“Reality itself,” write this volume’s able editors, “was for Pasolini always already divine in its secular expressiveness. ‘Being’ was for him not something natural, but stylized. ‘My vision of the things of the world, of objects, is not a natural or secular one; I always see things as a bit miraculous.’”

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in scholarly anthologies and has lectured at MIT, in New York, Milan, London, Los Angeles and many other venues. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 100 projects, including theater, national television, and award-winning films. He is completing a novel set in the 1960s.