Film Review: Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” — It’s the Apocalypse, Stupid

By Peter Keough

The greatest enigma Oppenheimer poses is recognizing the difference between good and evil and how to act accordingly.

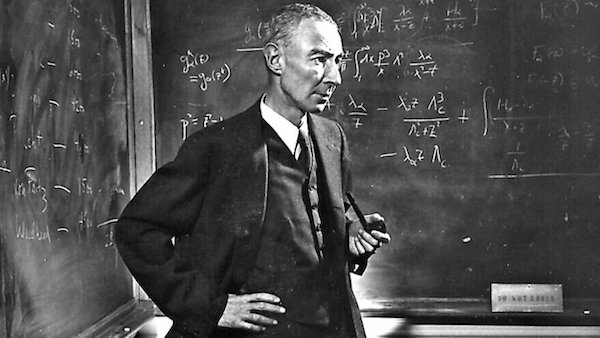

A scene featuring Cillian Murphy as J. Robert Oppenheimer in Oppenheimer.

As seen in his previous film, Tenet (2020), chronology can be a challenge in a Christopher Nolan film. This is true, too, in Oppenheimer, as are the concepts of space, energy, mass, and all the other certitudes that are overturned in a quantum theory universe.

Fortunately, Nolan’s version of the story behind the making of the A-Bomb and the unmaking of its maker does not succumb to the ill-conceived structural shenanigans of Dunkirk (2017). Nonetheless, you might consider reading the book on which it is based, Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s 720-page, Pulitzer Prize-winning American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, as the film’s form and style mirror the tricky physics. But perhaps the greatest enigma Oppenheimer poses is recognizing the difference between good and evil and how to act accordingly.

That dilemma is broached at the beginning of the film. In a bizarre 1925 incident combining Paradise Lost, the Oedipus Complex, and “Snow White,” a distraught Oppenheimer (played in a monumental performance by Cillian Murphy), after a montage of Promethean explosions and fire imagery, injects an apple with cyanide and leaves it on the desk of his Cambridge University tutor, the future Nobel Prize winner Patrick M.S. Blackett. Panicking, he returns just as visiting Danish physicist Niels Bohr (Kenneth Branagh with an accent worthy of German filmmaker Werner Herzog) is about to take a bite.

“Wormhole!” Oppenheimer yelps as he snatches the poisoned apple away before Bohr (whose appearance in this scene is invented for the movie; Oppenheimer in fact met him in 1923 at a lecture at Harvard) can take a bite. Thus he saves the pioneering physicist’s life and alludes to Nolan’s 2014 sci-fi epic Interstellar at the same time. Meanwhile, Bohr is advising him to pursue his studies in the hot new field of quantum mechanics. Oppenheimer does so, returns to the US, initiates a generation into the mysteries of the new science at Berkeley, and even finds time to investigate the conundrum of how stars collapse into black holes, a motif and image that recur with increasing aptness throughout the film.

Oppenheimer’s next challenge is political and personal, as he confronts an American society wracked with economic injustice and racism and a world succumbing to fascism. He takes an interest in the Communist Party because its members seem to be the only people who are doing anything about these ills. The allure of Party member Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh) doesn’t hurt. He impresses her with his multilingual proficiency (he has read Das Kapital in the original German), and by his Sanskrit edition of the Bhagavad Gita. She insists he recite from the latter while they do the deed. “I am become death,” he proclaims as they reach critical mass, “destroyer of worlds.”

When it comes to sex, sometimes you can be too cinematic.

As it turns out, Oppenheimer’s relationship with Tatlock would be disastrous for both of them, due in part to his erratic commitment — to Tatlock and to the cause of social justice — and to her psychological fragility.

Less demanding, at least initially, is Kitty (Emily Blunt), whose previous husband was a firebrand socialist killed while fighting in the Spanish Civil War. She is captivated by Oppenheimer’s fiery blue eyes and his sensuous explanation of the mysteries of the new physics (he points out how our bodies consist almost entirely of empty space and caresses her hand). After discovering she is pregnant she gets an amicable divorce from her third husband and marries the hot young genius. The film can be criticized for its dismissive depiction of the women in Oppenheimer’s life, but it is true to the times. Both Tatlock and Kitty Oppenheimer were highly accomplished in their own fields — respectively psychiatry and botany. They defied gender stereotypes and paid the price.

As was the case with Tatlock, Kitty’s connections with the Communist Party, however tenuous, would spell trouble for Oppenheimer. None of this was much of a problem, though, in 1939 when Oppenheimer and his colleagues were shocked to learn that the Nazis had accomplished the theoretically impossible and cracked the atom, releasing its power, and were developing its potential as a weapon. Despite his pacifism, Oppenheimer knew that the Allies had to have the bomb before the Nazis got it, and at any cost. When invited in 1942 by the head of the Manhattan Project General Leslie Groves to develop “the Gadget,” he readily complied.

Played with beefy bluster by Matt Damon, Groves might be the character that Oppenheimer feels closest to, and certainly is most comfortable with, as they banter together with near-Hawksian dialogue. That camaraderie, and Oppenheimer’s checkered past, make it easier for Groves to manipulate him when the goal of the project begins to shift. The Nazi threat of building a bomb fades and vanishes with their defeat. The new target, Japan, is also essentially beaten. It becomes clear that the real purpose of the bomb is to intimidate our erstwhile ally, the Soviet Union.

A photo of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Photo: Listening to America

Thus Groves demands that it be successfully tested before President Truman, newly installed after the death of Roosevelt, meets with the other Allied leaders in Potsdam, Germany in July 1945 to discuss the future of the postwar world. Truman makes an appearance late in the film; Oppenheimer pleads with him to share the secrets of the bomb with the world and avoid a nuclear arms race. “I feel I have blood on my hands,” Oppenheimer says. Truman, played by Gary Oldman, offers him a handkerchief and, as his visitor leaves, can be heard saying he never wants to see that “crybaby” in his office again.

Incidentally, having also played Winston Churchill in The Darkest Hour (2017) Oldman is just short a Stalin role in order to portray the entire Potsdam Conference as a one-man show.

But with the development of the thermonuclear “Super Bomb,” Oppenheimer drew the line. Here was a weapon so powerful that it was not limited to mere military targets. Instead, it was designed to destroy entire populations, a device that could effectively and indiscriminately achieve the kind of genocide that Oppenheimer had initially hoped the A-Bomb might prevent. He made his opposition known to the world, and, like Prometheus, was punished for his rebellion — not by the gods, but by the paltriest of men.

Therein lay his downfall, and to some extent, the film’s. The last third of Oppenheimer involves the machinations of Lewis Strauss, a petty, vindictive bureaucrat and the head of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), who magnified what he perceived as slights by the haughty Oppenheimer into a vengeful obsession. Despite the nuanced portrayal by Robert Downey Jr., Strauss never rises to the villainous stature of an Iago. He is a second-rate Salieri, and drags the other characters down to his level — with the bracing exception of Kitty Oppenheimer. She vainly tries to rally the menfolk into recognizing the danger Strauss poses and to fight back when, in 1954, Strauss orchestrates an investigation into Oppenheimer as a security risk whose membership in the AEC should be revoked.

Like A Beautiful Mind (2001) and The Theory of Everything (2014), Oppenheimer indulges in imagery, editing, narrative tricks, and other effects to dramatize the subjective experiences of its protagonist, including his abstract speculations, and does so with far greater success. Outside of his mind, though, much of Oppenheimer’s life took place in closed spaces cluttered with desks, blackboards, scientists, and politicians — labs, classrooms, committee meetings, and the inescapable hearings. These intercut and blur into one another like the realms of the dreaming minds in Inception (2010). Oppenheimer glimpses the deeper reality behind these appearances and occasionally that vision breaks through, as when the foot-stomping ovation he gets at a meeting celebrating the destruction of Hiroshima thunders out of control and turns into the roar of detonations, a blinding white light, an incinerated corpse crushed underfoot, and melting faces.

But, with the introduction of Strauss, the brilliance and urgency of this method dims, and the third act of the film verges on anticlimax. Cutting between Oppenheimer’s disastrous AEC hearing and a 1958 hearing in which Strauss is grilled about this affair while seeking confirmation of his appointment as Secretary of Commerce, Nolan tries to tap into the dynamics of a revenge tragedy.

This fizzles, but perhaps that is the point. When Strauss recalls, not for the first time, how Einstein (Tom Conti) snubbed him years before after talking to Oppenheimer and that he was sure it was because of something that Oppenheimer had said, an aide responds wearily that maybe they were talking about something important, and not about him at all. The film’s last, apocalyptic image suggests he was right.

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He had been the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, most recently For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

Tagged: Apocalypse, Christopher Nolan, Emily Blunt, Hiroshima, J. Robert Oppenheimer, atomic bomb, nuclear bomb

I have not read American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. I have read, and would highly recommend, 1995’s Hiroshima in America: Fifty Years of Denial by Robert J. Lifton and Greg Mitchell. From the introduction:

Ironically, Hugo’s lines resonate with the “psychic numbing” that has taken place after the global alarm over COVID. As of this month, according to the UN, 6,951,677 people have died of the disease, many of them unnecessarily.

Here is Greg Mitchell on Democracy Now (July 24) pointing out some of the flaws in Oppenheimer‘s fleeting looks at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

He is incorrect in saying the film does not question the use of the bomb on Japan. It’s a key issue. Also since the film focuses on Oppenheimer it confronts his responses to the bombing in key scenes not the actual victims themselves.

Thanks for both the review and the thought provoking comment.

An insightful review that was consistently entertaining to read, which is among the highest of compliments one could give a critic. I happened to see the MSNBC-TV documentary on Openheimer last night. I was amazed at how good it was for a commercial TV doc. (I saved the end for later because I didn’t want the Hiroshima affects on the population be the last thing I saw before sleep.) The decades on the childhood traumas of the pre-social Oppenheimer, and his subsequent rise to leadership, were especially compelling.

It’s always rewarding to read Peter Keough on film — this was tough one (Christopher Nolan — not my favorite director!), and Peter sailed through with his usual enthusiasm and clarifying insight.

Disclosure: Peter was a longtime colleague of mine at The Boston Phoenix.