Visual Arts Review: This Unique Place — Jeff Weaver’s Magisterial Paintings and Drawings of Gloucester

By Charles Giuliano

It is as poignant as it is ominous that Jeff Weaver will be among the last painters to document the last gasps of Gloucester as locals have known and loved it

Jeff Weaver, Tally’s Corner, 2003. Photo: courtesy of the artist and Cape Ann Museum

Europeans settled in Le Beau Port in 1623, renaming it Gloucester. The programming of Gloucester 400th Plus also acknowledges the millennia of indigenous people, primarily the Pawtucket, who “went silent.”

For this occasion the Cape Ann Museum has programmed a stunning year of special exhibitions. In 1923 Edward Hopper painted in Gloucester, where he met and later married the artist Josephine Nivison. A landmark exhibition celebrating the pair opens in late July, presented in collaboration with the Whitney Museum of American Art. Oliver Barker, director of CAM, told me during a recent visit that it will be “the greatest single exhibition mounted by the museum in its history.”

The Hopper exhibition is sure to overshadow its spectacular predecessor, This Unique Place: Paintings and Drawings of Jeff Weaver (through June 4), curated by Martha Oaks. That is unfortunate because it deserves equal billing.

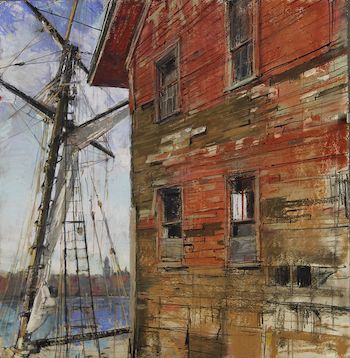

Jeff Weaver, Tops’l Schooner at Manufactory, 2020. Photo: courtesy of the artist and Cape Ann Museum

It could be argued that Weaver, a meticulous realist, is technically the better painter. The more imaginative Hopper is unquestionably the greater artist. It is savvy programming for the museum to present these masters back to back.

The richly varied topography of Cape Ann, starting in the 19th century with Fitz Henry Lane and Winslow Homer, has consistently lured many of the greatest American artists to live and work in the area. Weaver continues this tradition and his riveting paintings compare well to the best of his predecessors.

It is as poignant as it is ominous that Weaver will be among the last painters to document the last gasp of Gloucester as locals have known and loved it. Like Hopper, he is fascinated by the quotidian, generic, residential, and commercial architecture of what was once a thriving fishing industry.

When Weaver focuses on the fishermen’s homes in the waterfront Fort and Portuguese Hill or the processing plants and warehouses of the docks, his paintings represent the vestiges of old Gloucester. In the past few decades, starting with the development of Nugent Farm, condos have sprung up on every vacant patch of land with no end in sight.

What Weaver so painstakingly renders are the indigenous, vernacular structures that were built to be pragmatic, seemingly devoid of self-conscious style and design. It is the kind of “non-architecture” that is easily ignored or underappreciated. That’s no longer an option once we see them through Weaver’s eyes.

The artist is a plein air painter. A vitrine in the show displays his sketch pads and pastels. An image is worked up via an elaborate process. His primary concern is to evoke the precise play of light as it hits the texture of weathered surfaces. The paintings can only truly be appreciated when standing before them; this is delicate work that does not reproduce adequately. The museum has produced a well-illustrated catalogue with an essay by Oaks and brief comments by the artist, Barker, Ernst von Metzsch, and Don Gorvett. Regarding the color plates, however, they ain’t nothin’ like the real thing, baby.

As a painter Weaver is a man for all seasons. Some of the most engaging works are winter scenes. It’s the Gloucester that tourists never see.

We stood next to an older native visitor as she toured the exhibition. Looking over her shoulder we viewed a harbor scene painted in East Gloucester that looks toward the baroque tower of Town Hall. The water was flat and slate gray in the subdued light. “That’s just what it looks like in winter,” she exclaimed in wonder.

The scale of the pictures in the show varies from many small “portraits” of single houses to broad panoramas of commercial buildings and monumental minimalist renderings that evoke stark, modernist abstractions.

Like Eugène Atget’s early morning photographs of Paris, the paintings are generally unpopulated. Here and there we find a bundled up figure trudging along a snow-packed lane. One such picture, 2003’s Tally’s Corner, serves as both the cover of the catalogue and the work selected for the signage wall that welcomes visitors.

Jeff Weaver, Coll’s House, 2009. Photo: courtesy of the artist and Cape Ann Museum

Besides the ocean, another signifier of Cape Ann is granite, whose quarries were the area’s other major industry. That trade collapsed when construction morphed from using granite to concrete after WWII. Weaver rightly pays homage to this business in 2020’s Shed and Sea Wall, Hodgkin’s Cove and 2019’s Quarry Remnants.

The artist often positions his easel at odd and dramatic angles to his subject. 2021’s Beach Hotel Off Season is a quirky end view of a structure that looms over a generic slab of concrete wall. In 2018’s Tea House, we look up over an incline of rough boulders and a granite wall at a cropped white house under a brilliant sky. Intruding from the right edge is a slice of a roofed granite structure.

The once dominant fishing industry has been reduced to a few vessels. Locals can still buy lobster and scallops from boats off the dock. Weaver’s depictions of vessels and warehouses record the remnants of the era of Captain’s Courageous. His greatest gift: the way he captures the decay of structures and their dazzling reflections in still harbor water.

It is hard not to be transfixed before 2020’s epic Working Waterfront, the monumental simplicity of 2017’s Harbor Dock, the quivering light of 2016’s Reflections of Seawall, the sublimity of 2019’s Paint Factory, Afternoon Reflections, and 2017’s utterly smashing Beacon in Spring.

A norm of Weaver’s work is that it resists anecdote and narrative. Works like 2020’s Tops’l Schooner at Manufactory or 2014’s Paint Factory in Winter transfix us with their textures, which visually articulate benign neglect. Our eyes scan their battered surfaces with fascination.

Jeff Weaver, Lobster Dock, 2017. Photo: courtesy of the artist and Cape Ann Museum

The exception that proves the rule is 2021’s In Burnham Field. It’s as if the artist, for once, can’t maintain his objective, self-imposed austerity. In the foreground we encounter two silly snowmen with a row of houses in the distance. Here, indeed, is a hilarious picture that tells a rollicking story.

Some of his most triumphant work, most likely to be sought after by collectors and museums, embraces a stark, monumental, reductive geometry. The flat, dull catalogue reproduction does disservice to the 2022 masterpiece Blue Shed. Here the “narrative” is reduced to a single flat wall of a shed shimmering in the harbor below it. Others of its ilk include 2018’s Green Factory Wall and 2021’s Americold Series #1.

Significantly, what’s missing in this exhibition are depictions of the horde of blasphemous, hideous, Home Depot-sourced condos.

Charles Giuliano is in the final stage of publishing his eighth book, a collaboration with his sister, Annisquam: Pip and Me Coming of Age.

Tagged: American Painting, Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Jeff Weaver, MA

What an impressive exhibition. Truly, repros don’t come close. And, by all accounts, the artist is a fine, down to earth person. He is certainly worthy of wider renown.

As a Gloucester resident, Jeff Weaver’s work tears at my heart. His paintings capture the feel of Gloucester; I sense I am in his scenes and then remember actually being in them. Countless painters have painted the City, but Weaver captures it deeply and profoundly, holding history and its passing at the same time, and comforting the viewer with the beauty of his painterly surfaces.

Weaver is indeed a wonderful person, as well as artist. The exhibition is a fitting tribute to him and his work and a balm in these difficult times.