Book Review: “Künstlers in Paradise” — A Beach Read for the Cultured Sunbather

by Daniel Gewertz

This is a whimsical, well-written novel about an artistically respected Jewish family who managed to escape Nazi-annexed Austria at a perilously late date — September, 1939.

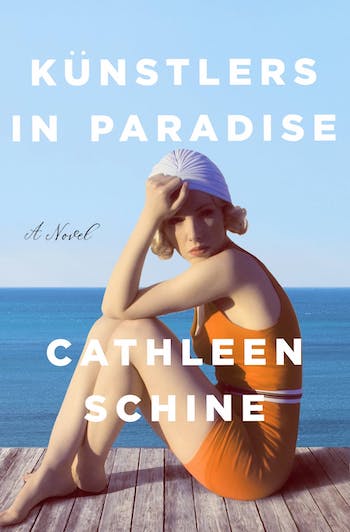

Künstlers in Paradise by Cathleen Schine. Published by Henry Holt and Company, 259 pages, $27.99.

“Do we really have to leave?” asks daughter Mamie Künstler, 11.

“We are lucky to have the chance,” replies mother Ilse.

“We’re refugees!” fumes the cranky grandfather, bitter about this forced exile from his homeland, from Vienna and all its cultural glories.

“We are lucky to be refugees!” retorts father Otto, a middling Viennese classical composer, who ends up teaching piano lessons to bored children in Los Angeles.

What saved the Künstlers from the death camps was Ilse’s job in the Viennese theater. The European Film Fund took up her cause, and the wife of an executive at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer responded. Despite the fact that Ilse knew barely a word of English, she copped a job as a junior level screenwriter at the princely salary of $100 a week.

The family’s first full day in Santa Monica, September 13, fell on daughter Mamie’s 12th birthday. They ate oranges and walked in “the odd, charming fog” of Santa Monica beach. By Thanksgiving, the family found themselves eating a lavish meal at a studio exec’s palatial home, with, among others, Greta Garbo in attendance.

Mamie soon becomes the protagonist of Künstlers in Paradise, Cathleen Schine’s 12th novel. (She’s best known for The Love Letter.) From the fast-moving first chapter, a reader might naturally expect further dramatics. But, surprisingly, drama has little to do with the rest of this novel. Instead, it is a whimsical, well-written work that is, at its core, an ever-winding story about storytelling itself. Call it an anti-drama. Or perhaps a romance. The author is in love with her main character, the brilliant Salomea “Mamie” Künstler.

Chapter two suddenly jumps 81 years, an almost bewildering leap in the narrative. Mamie is now 93: healthy, wise, a great-grandmother, and a former violinist of note. (She claims to be the only female to work as a studio musician in the whole recording industry of 1950s L.A.) The chapter opens with Mamie’s likable but strangely shiftless grandson, Julian, 24, visiting her from Brooklyn. It is 2020, and Covid will soon infiltrate the sun-drenched air of Los Angeles.

The drastic jump in time is the lone narrative shock in a cozy, captivating novel. This reader found it immediately disappointing to have been so rudely escorted out of the storied Hollywood era of 1939 and dumped into the pedestrian present. But it soon becomes apparent that the book consists largely of an inexhaustible batch of memories from Mamie’s long life, so the ’40s remain amply represented. Sitting beside her burgeoning garden in Venice, California, Mamie — like a nonagenarian Scheherazade — tells Julian the stories of her long life. She opens up in a way that she’d never do with her son Frank, Julian’s father. Fascinated, Julian copies down this rich flow of anecdotes into a Moleskine notebook. At first, he intends to use the tales for a ludicrous sounding sci-fi film he’s dreaming up. Ultimately, he realizes that capturing his grandmother’s life and wisdom is an end in itself. So, we are entertained by a troika of similar voices: Mamie unearthing her life to her grandson; Julian’s written version of Mamie’s tales, some delivered in monologist form to his new girlfriend; and occasionally Mamie speaking, it seems, directly to the reader.

Two famous real-life characters make appearances in Mamie’s young life: the aforementioned Garbo and the Künstlers’ fellow Austrian-Jewish émigré Arnold Schoenberg, the most exacting of the atonal modernist composers. Garbo befriends the girl with the gift of a Saint Bernard puppy. Schoenberg shows up as a friend of Mamie’s father, and later teaches Mamie how to play expert tennis. Both real-life greats are believably portrayed. In 1940, Schoenberg was 66, and known for his forbidding hauteur. But he was also a much sought music professor, both loved and feared. In the mid-’30s, Schoenberg was a frequent tennis opponent of his next-door neighbor, George Gershwin, so it is no stretch to imagine him teaching his eccentric but winning tennis theories to young Mamie a few years later.

While Schoenberg is an interesting character, the pages devoted to grandma Mamie lecturing young Julian about his complicated 12-tone experiments are the least appealing pages in the novel. Even Mamie questions her own wisdom about her yammering on with such thorny theories to an obliging 24-year-old with absolutely no interest in advanced atonality.

The third character living in the cute cottage is Agatha. It isn’t easy to define her role. Mamie found Agatha on a Venice street a few decades before, badly beaten, afraid for her life: the victim of a violent husband. She spoke little English. Mamie arranged for Agatha to stay in her backyard shed, and she never left. Decades later, Agatha still speaks in broken English. She cooks, cleans, and shops. In effect, she is both best friend and servant. Mamie jokingly describes her with the insulting term dogsbody, but Agatha is more grouchy captain than servile foot-soldier. She is also a very funny character.

Mamie, meanwhile, is an astute, intellectually quick conversationalist. The true virtue of Künstlers in Paradise rests on Schine’s ability to create interesting, amusing dialogue, often juxtaposing the spoken words with streams of thought that resemble a real brain at work and worry and play. It’s a talent not to be taken for granted.

Not only is Schine uninterested in chronological biography, but she does not appear to give a damn about many of the important landmarks in Mamie’s life. Mamie’s father, Otto, is an old-fashioned classical composer. Even in Vienna he was a minor talent. In L.A., he withers on the city’s cultural vines, composing little, forced to teach bored young piano students. At some point, he commits suicide. This act is barely mentioned. Similarly, young Mamie’s closest friend in the world — her grumpy, cigar-puffing grandpa — just fades out of the book without much notice. The narrative also gives short shrift to Mamie’s husband, who flew the coop early on in the marriage. Her life as a single mother is similarly unexplored. Her only offspring, Frank, is given a mite more notice, but only as her grandson Julian’s old man. Her self-edited proclivities as a storyteller take the helm. And tragedy is simply not on the program.

Is this lack of attention to life’s darker events a sign that Schine’s book is shallow? Not quite. It’s more that she has chosen to write a comedy, albeit one that begins with a whiff of catastrophic history. While high drama goes missing here, some portions of Künstlers in Paradise do reach for an elevated sense of enchantment. The conversations and thought-streams are consistently true to life. And yet one gets the firm sense that these lives — lived under the sun of L.A. and touched by the fables of Hollywood — have no truly dark corners. The small glories of life are embraced. The pain, fear, loneliness, terror: rarely mentioned. Think of it as a beach read meant for the cultured sunbather. Is it a page-turner? Not in any usual sense. Yet it still sails along with easy style and sparkling intelligence.

Julian is a character first presented to us as a parody of dippy Generation-Z lost-boy. He has no clue about a profession. He’s sort of brilliant, but in elaborately useless ways. For example: he learns a batch of exotic alphabets, including Japanese, but has no interest in learning any languages! He just wants to copy out already written words. While living in Brooklyn, his big “ambition” was to copy out Akira Kurosawa’s screenplay for Seven Samurai. This seems to stretch parody too far. It takes a while for the reader to care about this quixotic yet lackadaisical fellow.

Coronavirus hits a short time into his visit with Mamie, and with the fear of the illness all around — and an opportunity to be of assistance for once in his life — Julian stays on, realizing it is a gift for him to shelter in Mamie’s place. Julian is a passive, huggable overgrown boy who finds a sense of responsibility in the cherished presence of Mamie and Agatha. He may still be hiding from his future, but at least he’s serving a purpose.

Ultimately, however, the author doesn’t seem keenly interested in him. While walking Mamie’s Saint Bernard, he perambulates upon love with a female dog-walker, Sophie. But the slowly budding romance isn’t given the close attention that Mamie’s childhood adventures enjoy. Julian remains a supporting player in this L.A. story. Mamie is the undisputed star of the book, and when she falls, at age 20, into a love match with an older movie actress, Schine registers what an astonishing life highlight it is, despite its brevity.

Schine tends to exaggerate the lockdown period for the sake of a better story. Julian and his girlfriend, for example, seem to go on weeks of walks before finding out how they look beneath their respective masks. They hold their breaths while taking measure of their mutual countenances. It’s a cute scene, though a tad unbelievable.

Schine turns 70 this year. As an imaginative writer, she might well be less connected to today’s youth than to the young people who preceded her birth. The novel flutters to a close with a few chapters so short they seem less than climactic. Still, long before that, Schine’s vision has won our trust. In a novel that possesses the spark and imagination of Künstlers in Paradise, what stimulates the author’s creative energy tends to be its own reward.

For 30 years, Daniel Gewertz wrote about music, theater and movies for the Boston Herald, among other periodicals. More recently, he’s published personal essays, taught memoir writing, and participated in the local storytelling scene. In the 1970s, at Boston University, he was best known for his Elvis Presley imitation.