Film Review: “Little Richard: I Am Everything” — Homage to a Black and Queer Rock ’n’ Roll Icon

By Gerald Peary

There could have been more serious attention to the music, more of his immortal rock songs played start to finish. Otherwise, Lisa Cortés’s Little Richard: I Am Everything is the documentary about the Black and Queer rock ’n’ roll icon we’ve been waiting for.

Little Richard: I Am Everything, directed by Lisa Cortés. Screening at Somerville Theatre, Kendall Square, AMC Boston Common and other cinemas around New England.

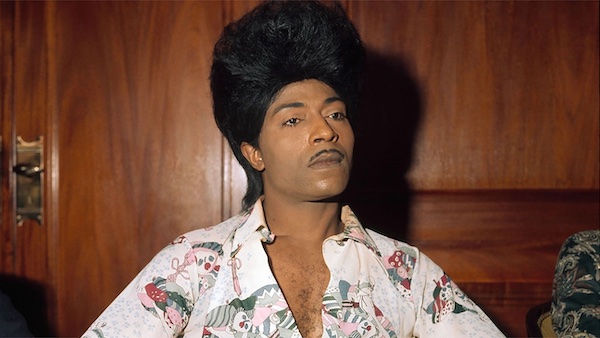

Little Richard in Little Richard: I Am Everything.

Growing up in the 1950s, I had insular white boy’s music taste. The first 45 record I bought was the double-sided smash, Perry Como’s “Hot Diggity,” and “Juke Box Baby.” My coveted first LPs, played over and again, were the greatest hits albums of Doris Day and Pat Boone. I watched The Lawrence Welk Show on TV with my mother and younger brother, and we all dug the all-Caucasian cast, both the lead singers and the background dancers, of Your Hit Parade. So imagine the adjustment for me when, at a segregated lakeside beach in South Carolina, someone put nickels in a portable jukebox and out came the screaming, screeching, yelping, howling, sweating, unmistakably Black sounds of “Long Tall Sally” and “Slippin’ and Slidin’,” sung out by someone called Little Richard. It was summer of 1956, I was 11, and I was totally enraptured. What can I say to express that ear-popping culture shock moment? “A-wop-bop-a-loo-mop-a-lop-bam-boom!” And what a leap for me from “Hot Diggity! Dog Ziggity” to “Good Golly, Miss Molly, she sure likes to ball!”

I wish there was more serious attention to the music, more of his immortal rock songs played start to finish. Otherwise, Lisa Cortes’s Little Richard: I Am Everything is the documentary about the Black and Queer rock ’n’ roll icon that we’ve been awaiting, with many ample testimonials to Richard’s worth, from a bemused Mick Jagger to sharp, articulate young Black gender scholars. I suppose Christians watching this movie could also take comfort in Richard’s often championing of the Church; but it’s discomfort for the rest of us, as every time he found Jesus he loudly refuted his homosexuality.

Richard Wayne Penniman was born in 1932 in Macon, Georgia, one of 12 children. His mother doted on him. His father wanted to kill him for being so effeminate. If Richard got anything from Dad it was his schizoid religious/secular personality. “Bud” Penniman was a strict preacher man who was also a nightclub owner and bootlegger. He took his son to Pentecostal churches, where Richard for the first time could go wild and feel all-over sensual while boisterously singing. But he carried with him for the rest of his life the shame of displeasing his father. “I did nothing good,” Richard would say much later, crying during a TV appearance. “He told me to get out of the house. Because I was gay, he put me out.”

A very interesting section of Little Richard: I Am Everything concerns the years before Richard achieved fame, when he went from band to band on the so-called Southern chitlin’ circuit, including performing in drag as Princess Lavone and actually finding several Black and gay performers as models: Billy Wright, from whom he took the high pompadour hairdo and the pencil mustache, and the very effete Esquirita, who taught Richard how to play piano. Says African-American scholar Zandria Robinson, “I will say this one hundred thousand times. The South is the home of all things queer, of the non-normative.”

Richard hit his all-time low when, penniless, he returned to Macon and got employed as a dishwasher at the segregated Greyhound bus station. “I couldn’t eat there, couldn’t use the bathroom,” he afterward remembered. But he was about to get his break, a chance to record in New Orleans with Specialty Records. “Blues wasn’t what I felt. Me and the young people was tired of all that slow music.” The song he chose was “Tutti-Frutti,” pure Little Richard, with screams and whoops and a great boogie-woogie piano bridge. As an academic described the joyous, frenzied song, it displayed “a desire to be erotically free put into a musical form that people could feel.”

Little Richard and the Beatles.

Perhaps no rock performer ever has had a year like 1956 for Little Richard, in which he released seven instantly classic singles, including “Slippin’ and Slidin’,” “Rip It Up,” “Ready Teddy,” “The Girl Can’t Help It,” and “Lucille.” But in 1957 Richard went off the deep end, suddenly abandoning popular music and the limelight by enrolling at the highly religious Oakwood College in Huntsville, Alabama. He literally burned his records, cut his hair, lived in a dormitory and walked about the all-Black campus with a heavy Bible. He got married! When he did return to recording, he made serious, somber gospel albums, these lacking any kind of rock ’n’ roll beat.

But this protean person made another turn in 1962, going over to England for a rock tour. Suddenly the flamboyance was back. “I am an atom bomb,” he declared, jumping off a balcony and into the audience in a colorful cape. He got divorced! Little Richard: I Am Everything stops its forward momentum to focus on the precious story of how in Liverpool he hooked up with four local rockers who had yet to record an album. “They was nervous. They never met no one famous before,” said Little Richard about the Beatles. John Lennon verified Richard’s account: “We were almost paralyzed with adoration.” “All my screaming numbers have to do with him,” said Paul McCartney.

When interviewed later in his career, Little Richard routinely did lots of bragging and name-dropping about all the people he influenced, starting with the Beatles and then hopping from James Brown to the Rolling Stones to Jimi Hendrix to David Bowie, and more. His narcissism could get mighty tiresome, even more when, with a testy ego, he bitterly railed at, his lack of recognition. But his most disappointing time as a human being came at the end of a debauched period in the ’70s of orgies, heroin, cocaine when he returned once again to the church and publicly denounced his sexuality. “I’m not gay now but I was gay all my life,” he proclaimed. “But God let me know he made Adam to be with Eve, not Steve.” He shouted out to the Lord, “Oh God, how can you save me? I’m homosexual. I’m not natural. I like men.”

Little Richard in Little Richard: I Am Everything.

“He existed in contradiction,” a music historian described him. Going into the ’90s, Richard was the guy who could tease in a TV interview, “If it don’t fit, don’t force it. Do you know what I’m saying?” In another he’d claim with a straight face, “I haven’t been involved with sex for 14 years.” The highest moment for Little Richard came in 1997 when, at 64 years of age, he was given the American Music Award, with testaments to his greatness from Keith Richard and David Bowie. There was a touching display of sincere tears when he marched to the stage with a whole auditorium standing and cheering. “It’s been a long time coming,” he said. “And I’ve been waiting.”

Though there were no more records after 1992, he kept performing and performing the old well-loved songs. And then — what else? — a final embrace of the church, Little Richard pushing everyone to “Get right with God,” before he died in 2020.

Gerald Peary is a Professor Emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston; ex-curator of the Boston University Cinematheque; and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema; writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty; and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His latest feature documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, has played at film festivals around the world.