Visual Arts Review: “Creative Alloys” — The Boston Metals Scene

By Mark Favermann

This exhibition provides a very thoughtful lesson in appreciating the poetry of practical objects.

Creative Alloys: The Boston Metal Scene at the Fuller Craft Museum, Brockton, MA, through June 4.

“Loopy” Brooch by Joe Wood, in Brushed Silver, 2002, silver electroformed from 3D print with patina, 2.5 x 3 x 1 in. Photo: Dean Powell

Like Sutton Hoo, King Tut’s Tomb, and Scythian Gold, the most exhilarating archeological finds are often the discoveries of beautifully crafted metal objects. A gorgeous shiny object suggests riches of untold value, something precious with which to feather our nests. Viewing the Fuller Craft Museum’s compelling show Creative Alloys is a bit like peeking at an elegantly revealed excavation filled with treasures.

Visually and viscerally interweaving notions of craft with expertise and artistry, Creative Alloys displays work by a dozen metal and jewelry artists working in and around greater Boston. These “creative allies” have formed what the organizers call a local “ecosystem,” a community inspired by productive passion. Over the years, the supportive artistic interchanges, constant get-togethers in which knowledge is generously shared, have made the region a major hub for the metalsmith craft.

So the Creative Alloys exhibition is the result of an eloquently playful aesthetic dialogue between artists past and present as it dramatizes a tension between tradition and experimentation, a blurring of the lines between perceptions of art, craft, and design. In this sense, the meticulous execution of the objects and jewelry here, part of an ongoing conversation between preferences for the primitive and the sophisticated, provides a very thoughtful lesson in appreciating the poetry of practical objects.

The artists showing in Creative Alloys are Jamie Bennett, Charles Crowley, Cynthia Eid, Sandra Enterline, Linda Kindler Priest, Rena Koopman, Deborah Krupenia, Claire Sanford, Sondra Sherman, Jill Slosburg-Ackerman, Munya Avigail Upin, Heather White, and Joe Wood. Each brings formidable craftsmanship and personal perspective to their creative objects, but a number of pieces stand out.

At the entrance to the exhibition Munya Avigail Upin’s two brilliant and mysterious silver “vessels” set a brilliantly enigmatic standard. The artist has called them “Memory Containers.” The first is the elegantly executed 934 7th Avenue (1983); the second is called Is she really your best bet? (1985). Both pieces are as beautiful as they are mysterious.

A Memory Container: 934 7th Street by Munya Avigail Upin, 1985, sterling silver and copper. Photo: the artist

Upin’s very personal imagery evokes both memory and possibility. The works are subjective celebrations of the past that inspire viewers’ imagination. Among her other standout pieces in the show are contemporary Jewish ceremonial objects, including a contemporary kiddish cup that is at once traditional in function yet given a very symbolic form.

Reminiscent of the iconic high speed Milk Drop photograph by Dr. Harold Edgerton, Joe Woods’ “Loopy” Brooch seems to harness a natural dynamism. Much of Wood’s work has developed from his meditations on structure, particularly the relationships among integrated ideas. He has been fascinated by the power of ornament — as parts of a larger whole or as elemental statements by themselves. He sees objects as expressive metaphors for tensile situations or conditions.

A true computer-aided creative pioneer, Wood adopted CAD software as a tool for his practice early, in the late ’80s. By 1999, as more powerful personal computers and new technologies for 3D printing emerged, he was creating solid forms for jewelry. His use of computer-based design gives a future-forward 21st-century aspect to his elegant creations.

Living in Two Worlds by Jill Slosburg-Ackerman, 1987, 1-inch-tall earrings in ebony, pre-ban ivory, pigment, and sterling silver. Photo: Stanley Rowil

Jill Slosburg-Ackerman is a true multimedia artist who flourishes as she creates works at different scales. Her Living in Two Worlds reflects some of the dualities she is experiencing in her life — as a citizen who feels that she’s a stranger in her own country, a mother and a child, a jeweler and a sculptor. The stark black-and-white of ebony and ivory, even the bicolored markings within the ebony, suggest a domain where opposites clash. Slosburg-Ackerman writes that she thinks of herself “as an intermediary in the studio whose vocation is to find harmony between seemingly contradictory parts.” Her work, a pair of earrings in three parts (the wearer leaves one behind), is a wonderful example of how she juxtaposes autonomy and interconnectedness.

Charlie Crowley is a renowned New England metalsmith, who uses traditional techniques in contemporary styles to create innovative holloware forms. (“Holloware” is the term used to describe kitchen and serving wares and other structures constructed from silver, sterling silver, or silver-plated copper.) Crowley often whimsically infuses “character” and individual personality into his works.

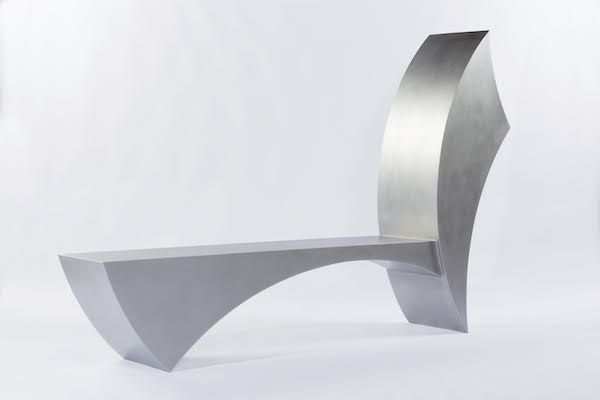

His skillful technical methods include carving, shaping, filing, and waxing. His focus on exploring how fluidly metal can be moved, shaped, and joined underscores his interest in joyfully playing with form and function. Like his Bench in the Creative Alloys exhibition, Crowley’s functional approach to art is about humanizing objects Here his geometry seems to suggest a figure who is lounging in comfort.

Bench by Charles Crowley, 2015, 64″ x 101″ x 18″ in aluminum. Photo: Jason Grow Photography

Rena Koopman’s Untitled necklace demonstrates her ability to make seemingly primitive, even natural shapes and lines strikingly contemporary. Her visit in the early ’70s to Japan to learn metalworking techniques has been the primary influence on her work. She deeply considers the tactile connection of what she produces, the relationship between object and body. She feels that jewelry only comes to life when it is worn. Her pieces are geometric yet soft, reflecting an interest in dovetailing the organic and the aesthetic. For her, the shape of a necklace should resonate with the arrangement of stones in a Japanese garden. The thematic underpinnings of her art are propelled by the minimalism of Japanese traditional design, the interaction between nature and human-made form.

Creative Alloys has been curated with an astute eye: this show justly recognizes the brilliance of the individual talents in Boston’s close-knit, internationally recognized metalsmith community.

Mark Favermann is an urban designer specializing in strategic placemaking, civic branding, streetscapes, and public art. An award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program and, since 2002 has been a design consultant to the Boston Red Sox. Writing about urbanism, architecture, design and fine arts, Mark is contributing editor of the Arts Fuse.

Tagged: Boston metalsmith community, Charles Crowley, Creative Alloys, Creative Alloys: The Boston Metal Scene, Fuller Craft Museum, Jill Slssburg-Ackerman, Mark Favermann