Book Review: “Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running”

By Gerald Peary

Anyone who cares deeply about cinema owes Jonas Mekas an abiding debt for all that he did for independent American filmmaking.

Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running Edited by Inesa Brasiske, Lukas Brasiskis, and Kelly Taxter. Contributions by Ed Halter, Melissa Ragona, and Andrew Uroskie. Yale University Press, 256 pages, 950 color + 50 b-w illus., $50.

Probably it was one of the last public appearances of Jonas Mekas (1922-2019), when the 95-year-old came to the Harvard Film Archive in January 2017 to speak with a series of his films and videos. What I recall was how matter-of-fact he was discussing his almost 70 years of productive artistry, how he refused to be sentimental about it. More, he showed no interest in providing answers when audience members urged him to pass on the secrets of his long fruitful life. The spirituality and philosophy of Mekas were not to be discussed. They were up there on the screen.

I met Mekas very briefly after an HFA screening and got him to autograph a book he’d written on the cinema. I knew better than to stand there and praise him. He would have hated that. But anyone who cares deeply about cinema owes Mekas an abiding debt for all that he did for independent American filmmaking, he who landed in New York in 1949, a penniless war refugee and Lithuanian immigrant. Soon, he found his calling, religiously attending screenings at Amos Vogel’s Cinema 16, where audiences gathered with excitement for an opportunity to watch independent cinema.

In 1950, Mekas purchased a 16mm Bolex camera and started random shooting, whatever caught his eye. In 1954 he founded and became editor of the exquisitely designed film periodical Film Culture, which featured rhapsodic articles in praise of both maverick Hollywood directors (Griffith, Welles, etc.) and far less heralded experimental filmmakers (Brakhage, Deren, etc.). In 1958 Mekas became the first film critic of the Village Voice, even prior to Andrew Sarris. And from his journalist perch, spinning off from Film Culture, he provided weekly cheerleading bursts for a host of highly idiosyncratic underground talents whom he soon labeled The New American Cinema. Hail Ron Rice, Shirley Clarke, Stan Vanderbeek, Strom De Hirsch, Willard Maas, and many others.

How could their obscure films be seen beyond their first screenings at coterie New York venues? In 1962, Mekas co-started the Film-Makers Cooperative, a distribution network for his band of underground directors. But ultimately what was needed was a permanent theater where their works could be shown on a revolving basis: the temple-like Anthology Film Archives, begun by Mekas in 1970 and still operative. What else did Mekas do besides writing a film column, running the Filmmakers Co-Operative, and programming the Collective of Living Cinema? Somehow he found time to make over 100 films and videos.

Jonas Mekas: The Camera Was Always Running is a handsome posthumous celebratory book put out as a joint project of Yale University Press and the Lithuanian National Museum of Art. The most obvious pleasures here are the vivid color stills from many of Mekas’s films. As a lover of ephemera, I liked even more the photos of odd antiquarian items culled from Mekas’s life, from passport photos to posters for underground film showings to letters of support for Anthology Archives from such luminaries as Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola. Between the many illustrations are tucked four essays by Kelly Taxter, Andrew V. Uroskie, Ed Halter, and Melissa Ragona about different facets of Mekas’s artistic life.

I give credit for this book not quite being a hagiography. The subject of the volume is characterized as being a bit of a “star-fucker,” hanging often with Andy Warhol (he called Warhol “the most productive filmmaker in the world”) and therefore gaining access to, among others, John and Yoko, the Velvet Underground, and Princess Lee Radziwill and the Kennedy family. Many such celebs make short appearances in his films. And the well-heeled were coaxed to keep afloat his costly artistic endeavors. Mekas in his film Walden: “I cut my hair to raise money, having tea with rich ladies.”

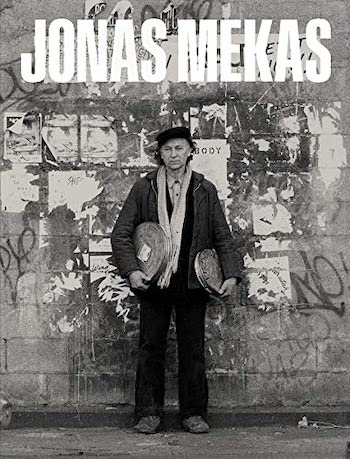

Jonas Mekas with camera. Photo: Boris Lehman

A magazine attack is cited in which the writer accused Mekas of being oblivious to the plight of Jews when he lived in Lithuania, essentially burying his head in books while the Nazis and then the Russians plundered his country. The attack seems to have some merit. As Mekas wrote in 1944, “I am a poet…. Let the big countries fight.… If you want to criticize me for my lack of ‘patriotism’ … you can go to hell!… I neither care nor want to understand you and your wars.” Throughout the book, Mekas is shown as being maddeningly apolitical, an anarchist only in his obsession with artistic and sexual freedom. He was opposed to the unionizing efforts of projectionists. He did have battles with the New York police, but that was when they were trying to shut down film screenings of the Living Theatre’s The Brig and of Jack Smith’s queer classic Flaming Creatures.

There is a fascinating chapter on Mekas’s 1964 filming of The Brig, his only work that found an audience outside of the underground community. He adhered to a method which he used routinely for his diary films, shooting from the hip with absolutely no preplan. He arranged a special performance of the play just for him, and he raced about filming up close while the actors went through their scenes. That was it. No second performance so he could get things right. As for his diary films, they contained multitudes, shots from many occasions in his life, past and present, pastoral scenes and images of war, famous people and unknowns, edited together in a fast, almost haphazard weave. A major influence in their construction was John Cage’s theories of “chance.” His final film, Requiem (2019), was the ultimate tribute to Cage’s dice-throwing aesthetic. Mekas used as a soundtrack Verdi’s Requiem, and wherever the music landed on the images: well, that was just OK.

Gerald Peary is a Professor Emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston; ex-curator of the Boston University Cinematheque; and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema; writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty; and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His latest feature documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, has played at film festivals around the world.

Tagged: Inesa Brasiske, Jonas Mekas, Jonas Mekas: the Camera Was Always Running, Kelly Taxter

Nice piece! You might check out the doc “Back from New York” at the Boston Baltic Film Festival about Mekas’s so-called “Lithuanian mafia.” https://bostonbalticfilm.festivee.com/back-from-new-york