Visual Arts Review: Marks from Elsewhere — Cy Twombly and Léonie Guyer

By Helen Miller and Michael Strand

It’s no wonder poets have been drawn to write about Guyer and Twombly’s work. We are carried away by an art that is always immediate, hic et nunc, but elsewhere too.

The contemporary and historical share the stage in two boldly poetic exhibitions in New York and Boston this season. In Nothing kept happening at P. Bibeau in Tribeca until March 4, Léonie Guyer’s works on paper and marble are clearly inspired by Cy Twombly’s legacy, particularly his approach to ancient Mediterranean culture, which is explored in Making Past Present at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston through May 7. Twombly and Guyer’s distinctive mark making holds our attention while leaving a trail of beguiling forms throughout these expertly curated shows.

Christine Kondoleon, Chair of the MFA’s Art of Ancient Greece and Rome, deftly pulls from its Greek, Roman, and Egyptian collections to accompany Twombly’s art in the museum’s contemporary wing. Surrounded by relics and ruins from his adopted homeland, the 20th century American expat is in his element. In the entryway to the main gallery, we encounter a photograph of Twombly in his apartment in Rome. The image, which appeared in Vogue in 1968, has been blown up and pasted like wallpaper (a big-institution gesture that can feel excessive but seems totally appropriate here) behind four actual busts from the artist’s collection. Yet, as Kondoleon and her collaborators astutely illustrate, Twombly’s interest is not antiquarian or classical. It is vitally contemporary.

Outside the zeitgeist of pop art and postmodernism, Twombly finds a kindred spirit in painter Léonie Guyer. A well-kept secret, even in the San Francisco Bay Area where she lives and works, Guyer’s paintings occasionally appear at venues in New York, where she was born. Guyer went west, Twombly, originally from Virginia, went east, but they both followed the light to an enriching counter-culture on the coast.

Across their respective exhibitions, Guyer’s shimmering shapes and Twombly’s flotillas of boats and roses traverse antique papers, fragments of marble, plinths and platforms. Guyer’s solo show at P. Bibeau is also an experiment in curation, with three of the four works on display at any given time rotating among 13 pieces from the artist’s prolific body of work. In a lovely gesture, Guyer leaves gallerist Bibeau to decide which piece to rotate into the mix each week. The gallery is small, a single room cutout in a converted neoclassical building (one cannot help but smile at the columns peeking out from under the sheetrock in the hall; the ancient world is everywhere — as Twombly and Guyer so beautifully demonstrate).

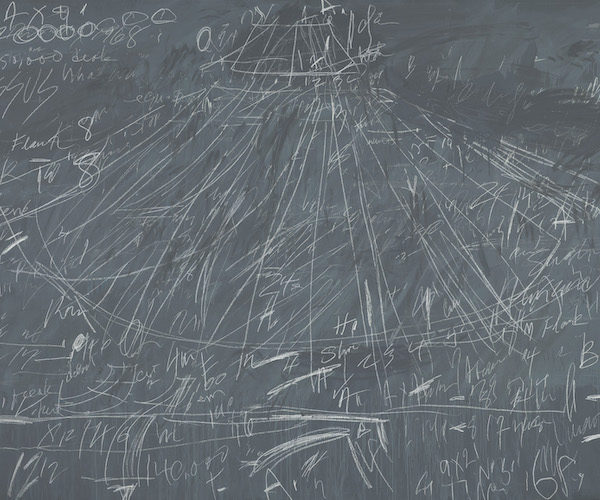

Cy Twombly, Synopsis of a Battle, 1968. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Photograph: Katherine Wetzel, © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

While Guyer shows no strict allegiance to the particular sources or classical canon evident in Twombly, her ethereal forms also come across as marks from elsewhere. The surfaces on which they appear are a testament to the persistence of material creation as well as the figurative association of other times and places. Attentive to what each shape on laid paper or harvested marble appears to be doing — how it contracts, expands, leans, curves, twists, and how it articulates and carries energy — Guyer’s pursuit reminds us of Richard Serra’s Verb List (1967) or the more comprehensive categories in Yuichiro Kojiro’s Forms in Japan (1965), which include “forms of continuation… forms of circling…” and “forms of transfiguration,” to name a few. Guyer’s work has probably never been compared to abstract expressionism or action painting, but activity is primary. Nor is Guyer’s affinity for minimalists like Fred Sandback — his crayon-colored, floor-to-ceiling string sculpture — far from Twombly’s geometric scribbles and canvas expanses. However diminutive, Guyer’s shapes draw direction and force from the incident and accident of their backdrops — the architecture of the surface, as one sensitive critic put it. Old paper and quarry stone carry a material history, structure and energy of their own, which resonates with Twombly’s sea and sky grounds.

Twombly’s Plato: A Painting in Two Parts (1977) features a large azure blue canvas joined by a smaller, offset square featuring only the cryptic names Plato, Phaedrus, Symposium, and Republic in slanted all-caps. By his own admission, Twombly had little interest in color; though here his color choice is perfect, echoing the 17th century French Baroque painter Nicolas Poussin, an earlier traveler to the same Mediterranean of whitewashed artifacts and blue skies. But lest we be deceived by its seeming placidity, the blue is set in motion by the runaway words, becoming formless, inharmonious, and unstable. Looking more closely, we catch the inconsistency of the brushstrokes. Twombly seems to complicate the story, showing that even in Platonic serenity there is dynamism.

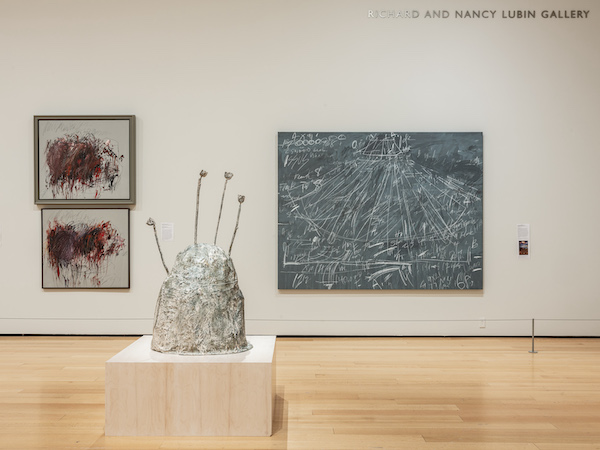

Making Past Present: Cy Twombly exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Linde Family Wing for Contemporary Art. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

A suitable phrase found on the wall text of the MFA gallery describes Twombly’s lines as “libidinal mark-making,” which would imply that, for him, the continuity of Greece and Rome, or Rome and Lexington, Virginia, where the artist grew up, takes the form of potential energy. What resurfaces is often erotic and demonstrative, performative in the sense of conjuring people, places, and their power by simply writing their names, and encoded too, echoing Twombly’s work as a young man in wartime cryptography.

In Vengeance of Achilles (1962) Twombly uses graphite pencil and wax crayon to sketch an evidently phallic, triangular, A-like symbol in swirled lines, all topped by a precipice of straighter, more deeply etched lines in cadmium red and alizarin crimson, coming to a prominent tip. His Untitled [Rome] (1964) features two versions of the same subject in a mess of graphite pencil, oil paint and wax crayon. Vigorous, swooping curves encase lightless black and red, pink, purple and orange, wet and dry smears: a bloody chaos builds up, particularly in the middle.

The result still feels interpretive. Even as the title cues us to Rome, where the paintings were made, a shield-like form emerges from the mass and — along with 5th and 6th century BCE armor installed across the gallery — prepares us for Twombly’s famous series, Fifty Days at Iliam (1978), a dedication to Homer’s epic poem. As relatively early explorations of Twombly’s contemporization of Greek and Roman mythologies, Untitled and Vengeance do not simply assemble the iconography of the past in order to honor it. They produce lively signatures that seem to implicate us in their immortality.

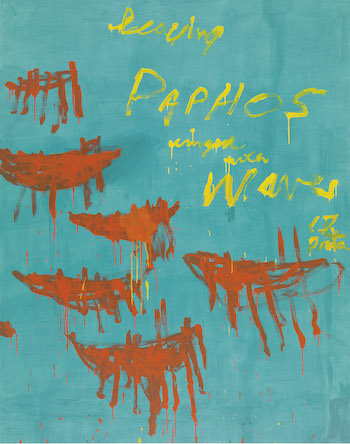

Cy Twombly, Leaving Paphos Ringed with Waves (III), 2009. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The more recent Leaving Paphos Ringed with Waves III and IV (2009) are large, dueling compositions, the most colorful (almost cartoonishly so) in the show. Here we find icons that Twombly more or less invented, or reinvented: dripping, fiery orange-red boats on backgrounds of turquoise house paint. The title of these works — a strikingly plaintive line borrowed from the 7th century BCE Greek lyrical poet Alcman — appears above and beside the boats, scrawled in the same hand in which the boats-and-oars were painted, in the same cadmium yellow used to mix the orange. While “wine-dark seas” and ancient Egyptian funerary models of wooden fleets — which Twombly is said to have admired as a student at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts — haunt the manic shapes, the elemental “finger-painting” of Twombly’s transgressive strokes also suggests vulvas, spiders, or even space invaders.

Twombly also decodes war zones for us: both directly and indirectly. In Thermopylae (1992), he casts in bronze what looks like an overgrown helmet and punctures it with a handful of flower-tipped sticks mimicking arrows extending feet from the weighty base. In Synopsis of a Battle (1968) Twombly coats a canvas with oil-based house paint of a similarly bronze-hued gray blue, then takes a white wax crayon, radiating lines in a half-spoke or oval shape. The result looks like the giant chalkboard of a maniacal teacher on which he is scrawling cryptic numbers and unintelligible symbols for a bewitched class. The Vietnam War was raging, and Twombly’s contemporaries, including the German artist Joseph Beuys, were incorporating instructional tools like blackboards into their performance lectures on social issues. Twombly adapts a similar motif to translate the early German landscape painter Albrecht Altdorfer’s The Battle of Alexander at Issus (1529), a rendition of the famous battle from 333 BCE in which Alexander of Macedon (e.g. “the Great”) shockingly defeated the armies of the Persian emperor Darius.

One would be hard-pressed to uncover a war in Guyer’s work, more like warriors in the off-hours, perhaps. There is something anthropomorphic about many of the figures, but the energy is different. Guyer’s thoughtful color mixing and organic angles are more careful, and caring, than Twombly’s rapid-paced, haphazard, outside-the-box mark making. His colors can also be a bit garish, awkward, or drunk on love more likely. In contrast, a delicacy and slowness runs through Guyer’s work, which is not to say that birth and death are absent from the Bibeau show.

Guyer’s Untitled no. 113 (2020) leans against the wall on a slender ledge, welcoming us into the gallery. The heaviness of the substrate is wonderfully incongruous with the sensuality of the slightly viscous red oil paint. We are struck by the work’s seductive combination of forms — handle, opening, ichthys, all suggesting passage from one world, or void, to the next. The piece appears to simultaneously hold dominion and promise access to other realms, and is legible, unlike many of the works on paper, from across the room. It is the one piece that remains on display for the duration of the show.

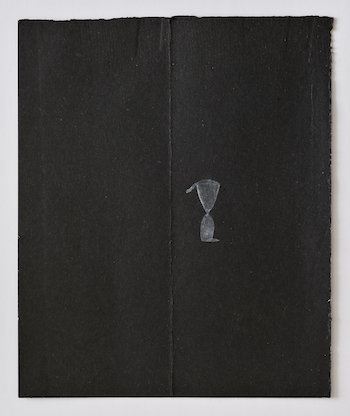

Léonie Guyer, Untitled OBP-14, 2019. Photograph: Graham Holoch, courtesy of the artist.

Activity invites studious exchange: we look, the work calls us over, we look closer. We see something. There is the initial gestalt of geometry — the essential impression or shape — and the double take, in which an unexpected triangle or wing-like shape appears. It’s as if the lights went off as we were approaching the art, and our eyes now have to readjust.

Indeed, Guyer’s shapes recall the way objects intermingle in the dark or in a photograph. Untitled (2020) is an especially small drawing in charcoal on Japanese paper in which we find this sort of blending or merger, with two roughly oval forms joined at the top and bottom respectively, yet each with their own distinctive appendage. If we’ve never seen this shape in an artwork before, we might recognize the curve from the feel of a favorite spoon or sponge (it’s somehow that quotidian and modest yet also special), or from the arc of a thought, the step in a dance. No two visitors will find that it unfolds for them in quite the same way.

A similar freedom can be found in Twombly’s work, facilitated by the successful arrangement of the MFA show, which is akin to a mind map, as artist and educator Dan Serig recently observed in a lecture on the form, and made up of inspired scrawls, haptic lines, and layered connections. The associations are philosophical and concrete, but also open-ended. Even as the installation establishes Twombly’s art in relation to a Greco-Roman inheritance, particularly as a ballast or anchor for his poetic sensibility, the artist still revels in the indefinite. Twombly reaches for spontaneity in every mark, even in names.

Léonie Guyer: Nothing kept happening at P. Bibeau Gallery. Photograph: Michael Popp, courtesy of P. Bibeau Gallery.

Guyer’s work, which does not rely so explicitly on a store of historic references, searches too. But it does not reach. To access the underlying continuity of existence, what some spiritual traditions refer to as consciousness, the artist would appear to become still and listen, achieving a focus that we all share. Each standalone manifestation, realization, or resolution of this beginning-and-endlessness — each unique, idiosyncratic shape — speaks the influence of Tantric art and Buddhism on Guyer’s practice. Meditative visualization explored by Tantric groups in 12th century Nepal and current day Rajasthan is one source of Guyer’s interest in timeless forms of formlessness.

Seen in the context of Guyer’s recent exhibitions and publications, the Bibeau show is something else, something new. Her 2018 exhibition at the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art in San Francisco included a Shaker gift drawing, a small wooden Shaker box, 2,000 year old glass vessels from the Roman Empire, and Children’s Tapes (1974) by Terry Fox, a video of actions in which everyday household items such as forks are magically transformed for the artist’s son — displayed and screened alongside a range of Guyer’s work. LEONIE GUYER-ARCHIVE, published by LAND AND SEA in 2021, contains the artist’s seemingly infinite, illuminating studies, iterations, and variations of recurring shapes on precious scraps and tracing paper. Just as the continuity between Twombly’s iterative art and that of famous poets and anonymous craftspeople complement and co-create at the MFA, the four walls of P. Bibeau provide the perfect shape in which to reexamine and more deeply appreciate Guyer’s vision.

These details of installation are not immaterial, as the experience of both exhibitions, if we can summarize it in a word, is transportation. It’s no wonder poets have been drawn to write about Guyer and Twombly’s work. They come to us in the spirit of the present, though just as quickly as we enter the galleries do we leave this time and place, carried away by an art that is always immediate, hic et nunc, but elsewhere too.

Helen Miller is an artist. She teaches at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and Harvard Summer School. Michael Strand is a professor in Sociology at Brandeis University.