Visual Arts Review: “Matt Pawleski/Matrix 191” — Flirting With the Functional

By Peter Walsh

Instead of adoring function from an aesthetic distance, Matt Paweski confronts it where it lives. These sculptures play with the self-insistence that function has always had in modern design.

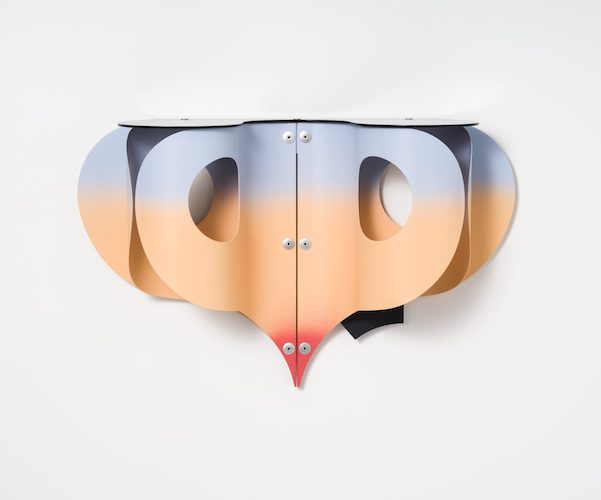

Matt Paweski, Bonnet (Shaker), 2022. Aluminum, fir plywood, aluminum rivets, aluminum hardware, vinyl paint, enamel, plastic. Photo: Ruben Diaz.

The works in the Matt Pawleski/Matrix 191 exhibition, on view at the Wadsworth Atheneum through May 7, flirt with the functional the way a Raymond Loewy locomotive or a Harley Earl concept car flirts with the sculptural. They are subtly subversive. Signs posted at each entrance to the show say: “While the sculpture in this gallery may suggest functionality, please do not touch or sit on the artworks.” So “this is not a chair” is the meta-message of the several examples of works titled Chair and placed throughout the gallery, as if offering visitors a place to sit. But not really.

Paweski, born in Detroit, grew up in Arizona and studied art at Arizona State while simultaneously working as an apprentice painter and assistant for a commercial sign and display fabrication shop. After graduate studies in Pasadena, he settled in Los Angeles. All of the pieces at the Wadsworth, made in 2022 expressly for this show, the artist’s first solo museum exhibition, suggest a kind of idealized Southern California aesthetic: perfectly finished painted surfaces that conceal and unify the materials underneath; playful, warm climate colors; fanciful, dreamlike shapes; and an impressive level of perfection that is made to seem casual, unassuming, and effortless. Paweski has divided the Matrix galley into domestic-scaled spaces that could be rooms in a futuristic apartment inhabited only by robots or a spotless workshop where only thoughts are manufactured.

Matt Paweski, Heart Shelf, 2023. Photo: Ruben Diaz.

Paweski’s primary material is cut and shaped aluminum, supplemented with plywood and plastic, but the beautiful paint— pale yellow, watermelon pink, lawn chair green, tropical beach orange— perfectly applied, unifies and dematerializes it into pure sensation. Each piece in the show has its own color. Aeronautical-grade aluminum rivets, left in their polished natural state, quietly hold things together. Here and there, a flat mirror in polished aluminum peaks out from a curving intersection of shaped planes. The pieces are neither particularly large nor especially small; the colors neither bright nor dull. The shapes are extravagant, mostly symmetrical, thin-edged, curving and folding into sensuous shapes that are vaguely familiar — from mid-20th-century furniture, Danish cookware, perhaps.

One piece, Mirror Lamp, crosses the line into functionality and is actually a working light fixture. It hangs in numbers from the ceiling of a middle space in the show. Others, like Heart Shelf, hang on the walls or stand on custom-fabricated pedestals. Most are symmetrical or partly so.

Two pieces — Bonnet (Shaker) in green and Vessel (Butter) in yellow — are table-like forms with a void down the middle in which a complex shape rests as if it might slide on a hidden track. They suggest table saws in a woodworking workshop or machine tools in a factory. They are among the most intriguing and perplexingly non-functional works in the show.

What would happen to these sculptures in a real domestic space? Would breakfast be served on the non-table tables? Would Hummel figures accumulate on the non-shelf shelves? Certainly the non-chair chairs would get sat on. These scenarios suggest a certain level of perversity, a case where form, or at least the definition of form, defeats function. If the works themselves were not quite so appealing, they might even provoke anger or vandalism.

Matt Paweski at his exhibit at the Wadsworth Atheneum. Photo: Wadsworth Atheneum.

Pawleski warns in a gallery guide against taking for granted the “hyper-technological world” where “so much of what makes our lives possible is invisible and unseen.” “The sculptures are… an anchor or trap to catch someone, give them pause… A service interrupted that leads to something greater. There is a positivity to the uselessness of the sculpture.”

A love of function, almost a yearning, for power, for the vitality of the machine, runs through much of modern art since the turn of the twentieth century: the Italian Futurists, the Russian Constructivists, Charles Sheeler’s factories and industrial landscapes, Bernd and Hilla Becher’s water towers, all lean towards what Pawleski seems to lean away from. Instead of adoring function from an aesthetic distance, he confronts it where it lives. These sculptures play with the self-insistence that function has always had in modern design. The effort may equally lead to something useful or into a blind alley, but in this show it is at least a momentary pleasure.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in scholarly anthologies and has lectured at MIT, in New York, Milan, London, Los Angeles and many other venues. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 100 projects, including theater, national television, and award-winning films. He is completing a novel set in the 1960s.