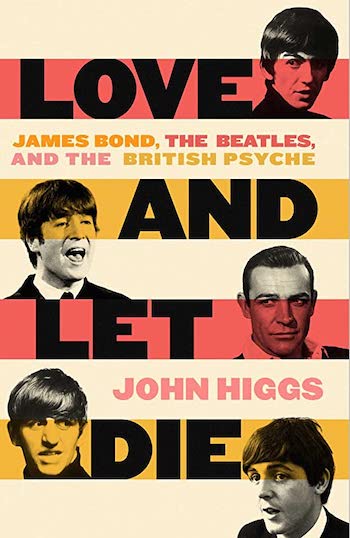

Book Review: Love, Death, the Beatles, and James Bond — Britain, for Better or Worse

By Adam Ellsworth

There’s no question the Beatles come out of John Higgs’s superb book Love and Let Die looking far better than James Bond. Love tends to play better than death and it’s easier to root for working class underdogs than Establishment snobs.

Love and Let Die: James Bond, the Beatles, and the British Psyche by John Higgs. Pegasus Books, 516 pages, Pegasus, $29.95.

“Love” is the first word sung on a Beatles record. It’s also the second word, which really shouldn’t work, but “Love, love me do” rings right every time you hear it. Nothing could be more simple. Even by the standards of a debut single, “Love Me Do” is a simple song. Lyrically, the tune includes a mere 107 words, 24 of which of course are “love.” Musically, it’s strictly G and C, before D arrives in the middle eight. If rock and roll has taught us anything, though, it’s that you only need three chords, especially when they’re carrying a truth as true as our human need to be loved.

“Love” is the first word sung on a Beatles record. It’s also the second word, which really shouldn’t work, but “Love, love me do” rings right every time you hear it. Nothing could be more simple. Even by the standards of a debut single, “Love Me Do” is a simple song. Lyrically, the tune includes a mere 107 words, 24 of which of course are “love.” Musically, it’s strictly G and C, before D arrives in the middle eight. If rock and roll has taught us anything, though, it’s that you only need three chords, especially when they’re carrying a truth as true as our human need to be loved.

The Beatles loved love. It was the primary theme of their work, from “Love Me Do” to “The End.” In their songs, love could be joyous (“She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah!”) or perplexing (“It’s only love, and that is all. Why should I feel the way I do?”), but either way it’s all you need. And since you can’t buy it, everyone gets to experience it. Love is, in the best sense of the term, common.

James Bond never had time for love. Sex, sure, though all the women he bedded eventually ended up dead, so love was probably never in the cards. 007 wasn’t interested in what was common either. He was a solid member of the Establishment (just like his creator, the author Ian Fleming), with no real concern for the greater good. Okay, so he saved the world from time to time, but that was just his job. The thing he had to do to justify having a license to kill.

Of the 25 official Bond films, six have “die” or “kill” in their title. “Live” surprisingly shows up in three titles, though they’re “Live and Let Die” (no question where the emphasis there is), “You Only Live Twice” (which does imply at least one death is needed to get to the second life), and “The Living Daylights” (a thing that is typically knocked out of you), so we needn’t read too much into that. The first of the franchise, Dr. No, features neither “die” nor “kill,” although there’s plenty of killing and death in the movie, and besides, “no” is its own kind of negation.

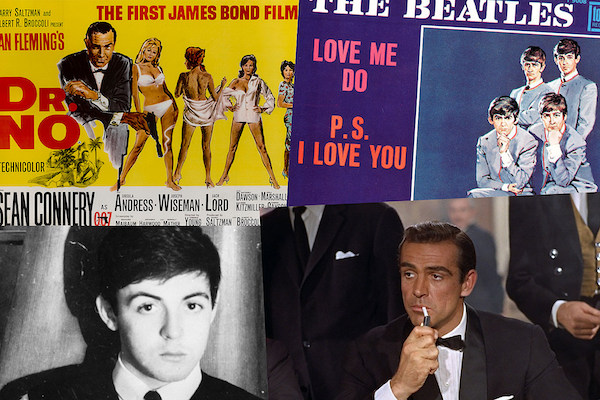

Dr. No and “Love Me Do” were both released in the UK on October 5, 1962. Life is full of coincidences, and coincidence is probably all this is. It can certainly feel like more than that, though, especially if you consider, as John Higgs does in his superb new book Love and Let Die: James Bond, the Beatles, and the British Psyche, that Bond and the Beatles were not just twins unleashed on the world on the same day. They were opposite but intertwined phenomena that reflected and shaped the country that gave birth to them. They were, and perhaps are, Britain, for better or worse

“According to Freudian psychologists,” Higgs writes in Love and Let Die’s introduction, “love and death are the two central opposing drives in the human psyche.”

To put that in ancient Greek, humans are torn between Eros, the desire to love, be loved, and be part of the collective, and Thanatos, the compulsion to hurt (or worse) ourselves and others. The former is about being a member of the group. The latter is a solo trip.

Bond obviously worked alone, and he made it clear early on that whatever trip John, Paul, George, and Ringo were on, it was beneath him. In 1964’s Goldfinger, at the very height of Beatlemania, it’s suggested to 007 (played by Sean Connery) that he needn’t go through the trouble of chilling a bottle of champagne after the ice in its ice bucket has melted. “My dear girl,” he replies, “there are some things that just aren’t done, such as drinking Dom Perignon ’53 above the temperature of 38 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s just as bad as listening to the Beatles without earmuffs.”

This about summed up the Establishment view of those scrubby Scousers. Higgs reports that Bond producer Cubby Broccoli was offered the opportunity to produce the Beatles’ first film, A Hard Day’s Night, but he turned it down to make a Bob Hope movie instead. Playwright Noël Coward, a close friend of Ian Fleming, hated the Beatles and wrote in 1965 that the decision to give the Fabs MBEs was “a tactless and major blunder” and continued that “some other decoration should have been selected to reward them for their talentless but considerable contributions to the Exchequer.”

England’s upper crust could keep telling themselves the Beatles were talentless for the first few years of the band’s career, but by the time of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in 1967, the music had become too sophisticated for even them to ignore. At that point, a new strategy was warranted, so like all well-adjusted people, at least some of them turned to conspiracy theories. A Mr. Hogg, the music teacher at writer Hanif Kureishi’s comprehensive school, for example, explained to a 13-year-old Kureishi that the Beatles did not write or perform their music. This was instead done by their manager Brian Epstein and producer George Martin. They had better accents after all, and far more respectable hair.

As absurd as these conspiracies and general denials of the Beatles’ talent were, they are almost understandable when you consider how badly the band shook the belief system of an entire class of people. “The arrival of the Beatles was a profound challenge to the British status quo,” Higgs argues. “The Beatles hadn’t gone to the right schools, and they were certainly not from the right families. They were northern, and they were not deferential. How was it possible that they were more talented songwriters than their social betters?” For the Bondians of the world, it was best to put on their earmuffs and not consider the answers to such questions.

Despite the hate from Her Majesty’s Secret Servant and his ilk, the Beatles were quite keen to enter Bond’s world. Hence their second film, Help!

The band didn’t actually play secret agents in Help!, but the movie could never have existed without James Bond. It’s filled with gizmos and gadgets and baddies and comically absurd situations (a bomb in a curling stone? Why not!). As far as mid-’60s comedies go, it’s an enjoyable viewing experience. But Help! is also the least vital of the Beatle films. It lacks the wit of A Hard Day’s Night, the imagination of Magical Mystery Tour, and the wonder of Yellow Submarine. Help! is just kind of zany, and deep down the group knew it wasn’t for them.

“The Beatles had wanted to be in a Bond film,” Higgs writes, “because that was the ultimate male fantasy [British] culture offered up, but when they did this it proved to be limiting and less thrilling than they had hoped. Britain’s pinnacle of wish-fulfillment was okay, but surely they should be coming up with something better?”

“Something better” ended up being the recording of Rubber Soul, Revolver, Sgt. Pepper, the White Album, and Abbey Road, not to mention all the A-sides and B-sides in between. These are records filled with love. Like the music that came earlier in their career, much of this love is between individuals, but the band also branched out into songs about a higher kind of love. Exhibit A would be 1967’s “All You Need is Love,” which Higgs describes as an expression of agape, a “universal, unconditional love for all, such as that felt by God for man and by man for God.” Certainly not Bond’s cup of tea.

It’s no surprise then that the next time a Beatle would enter the world of 007, it would be after the band had broken up. 1973’s Live and Let Die featured a score by George Martin, and a theme song by Paul McCartney himself. Macca desperately needed a solo hit, and with “Live and Let Die,” he got one. The tune is a stone cold classic, though it features a very un-Beatle-like sentiment: “You used to say, ‘live and let live.’ But if this ever changing world in which we’re living, makes you give in and cry, say, ‘live and let die!’”

Not exactly “All You Need is Love,” but then again, Paul was no longer a Beatle. Had he turned his back on love? Of course not, but even he couldn’t be all Eros all the time. The death drive is present in all of us.

There’s no question the Beatles come out of Love and Let Die looking far better than James Bond. Love tends to play better than death and it’s easier to root for working class underdogs than Establishment snobs. Even Bond though gets a shot at redemption.

Higgs ends his book in the 21st century, with the 25th 007 film, No Time to Die. Sean Connery is no longer playing the super spy, and he hasn’t since 1971. Connery’s original Bond was succeeded by George Lazenby, Roger Moore, Timothy Dalton, Pierce Brosnan, and now, Daniel Craig, who in No Time to Die does the most un-Bond thing imaginable. He chooses love.

Not easy love either. Final, pure, true love. The basic plot is this: while trying to save the world (again), James is infected with DNA-carrying technology that will activate if he touches his wife and daughter, and once activated will kill not him, but them. Armed with this knowledge, there’s only one thing for him to do. Die.

On the surface, this is typical Bond. Death, death, and more death. It’s obviously more than just that though. Only someone who has completely surrendered to love is willing to take on that kind of death. No Time to Die then offers Eros and Thanatos in perfect balance, which is to say, they’re both present, but ultimately, love wins. Someone should really write a song about that.

Adam Ellsworth is a writer, journalist, and amateur professional rock and roll historian. His writing on rock music has appeared on the websites YNE Magazine, KevChino.com, Online Music Reviews, and Metronome Review. His non-rock writing has appeared in the Worcester Telegram and Gazette, on Wakefield Patch, and elsewhere. Adam has an MS in journalism from Boston University and a BA in literature from American University. He grew up in Western Massachusetts, and currently lives with his wife in a suburb of Boston. You can follow Adam on Twitter @adamlz24.

Tagged: Beatles, British Psyche, James-Bond, John Higgs, Love and Let Die: James Bond

And maybe the most quoted of all Bond-film lines? “Confess? No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die!” Thanks for this fun review.