Visual Arts Review: The Iconic Gropius House — An Exquisite Bauhaus Masterwork

By Mark Favermann

Homage to a Modernist architectural gem located in the woods of Lincoln, MA

Exterior of Gropius House, built 1938. Photo courtesy of Historic New England

Considered one of the most influential architects of the 20th century, Walter Gropius (1883-1969) was a highly celebrated German architect and master teacher. He was the visionary founder and first director of the legendary school of design known as the Bauhaus, in Germany (1919), among the leading proponents of what was known as the International Style in 20th-century modernist architecture.

Gropius was also a founding partner of the once flourishing, now defunct architectural firm The Architects Collaborative (TAC) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. After leaving Germany by way of England to teach at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design in 1937, he designed his new family house, which was completed in 1938. This unlikely Lincoln, Massachusetts, modernist architectural gem was Gropius’s home until his death in 1969.

Though considered somewhat modest in scale compared to many other houses in the area, the residence’s visual and aesthetic impact was revolutionary at the time, especially in a rather conservative community. Modernist structures were not very common in the US during the ’30s — and rare as hen’s teeth in staid New England.

The Gropius approach was very innovative for that era: his vision combined what he considered the traditional elements of New England architecture with innovative industrial materials rarely previously used in domestic settings — including glass block, acoustical plaster, steel lighting sconces, and chrome banisters. These were combined with the latest available technology in mass-produced fixtures, especially in the bathrooms and the kitchen. Now maintained by Historic New England, the structure’s exquisite setting, open floor plan, and elevated site make for a spectacular tableau.

Gropius House Interior, built 1938. Photo courtesy of Historic New England

Though visually striking, the house was built with economy in mind. At a time when conventional houses cost $5,000 to $7,000 to build in the late ’30s, total construction costs were around $25,000. In keeping with his Bauhaus philosophy, Gropius carefully planned every aspect of the house and its surrounding landscape for maximum design efficiency and maintenance simplicity. The living space contains an important collection of furniture made for the family in the German Bauhaus workshops during the ’20s and designed by former Bauhaus teacher, the Hungarian-born Marcel Breuer, who was also a noted architect and designer. The design of the house was carefully crafted to accommodate this furniture.

Many family possessions are still in place. Artwork includes personal gifts by Josef Albers, Joan Miró, and Henry Moore. There is even a small sculpture by the Boston-based William Wainwright, a friend and architectural colleague. Interspersed with these are objects from Gropius’s foreign travels, including pieces of Pre-Columbian art.

The house’s entry and hallway illustrate the designer’s interest in drawing on traditional New England forms and construction ideas. The central hall with doors at both front and rear are rather reminiscent of 18th-century homes. This approach ensures cross ventilation. Immediately inside the front door is a mudroom, separated from the hall by an inexpensive curtain rather than a door. This could be closed to keep out the cold and opened to enhance ventilation.

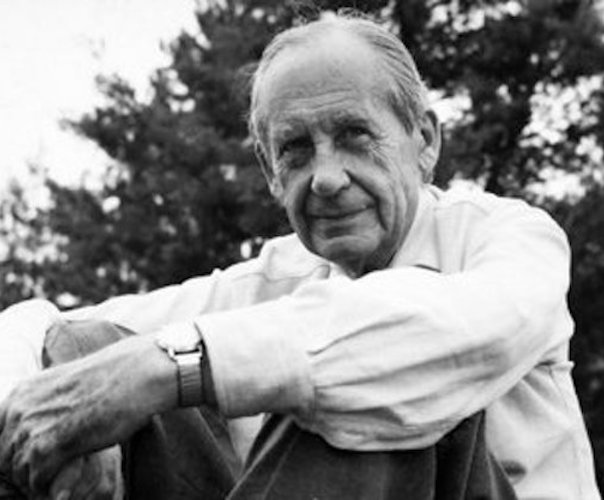

Walter Gropius — a legendary figure in the history of architecture. Photo courtesy of Historic New England

White clapboards, a traditional New England material, are used in a nontraditional way to great effect. The clapboards were brought inside and applied vertically; Gropius’s wife Ise felt that “their narrow vertical shadows relieve the white blandness and make an excellent background for artwork.” The central stairs, again a New England tradition, were also modified by Gropius. The unusually curved staircase faces away from the entry, implying that the upstairs is a private space.

The building materials used in the hallway are quite unusual in a residential setting. The floor is a resilient cork tile, and the ceiling is made of acoustical plaster. Both materials are sound absorbing. They are both durable, functional, and in this setting, quite surprisingly elegant.

The lighting throughout the house is also very distinctive. Gropius used glass blocks and floor to ceiling windows to transmit natural light to this area. He installed commercial steel-plated wall sconces to provide both indirect light and dramatic shadows when lit in the evening.

The master bedroom suite contains many innovative design details, an elegant reflection of Gropius’s economical use of space. A glass wall separates the dressing room from the sleeping area, which creates the illusion that you are in a much larger space. This design also solved a practical problem of day-to-day living: the wall separates two heating zones. The culturally European (very German) Gropius couple slept with the windows open all year round. This design allowed them to sleep in a cold environment but dress in a warmer one. There is also a curtain that could be closed for privacy. The door could be closed to keep out noise. Not afraid to make her own design statement, Gropius’s wife would often leave a bright colored dress hung on the door, usually a red one, to add a color focal point to the room.

There are a few distinctive features on the exterior as well. Wrought iron stairs allowed Gropius’s daughter to enter the house with her friends without going through the downstairs. There is also a roof deck adjacent to her room that offers great views of the surrounding countryside. A wall there is painted a wonderful shade of pink, which adds a subtle touch of color to the rather colorless deck.

Gropius House, built in 1938. Photo: Mark Favermann

At the back of the house is a screened-in porch. The Gropius family took their meals here in moderate temperature months and played table tennis — yes, ping-pong — in the winter. Visitors are shown a photo of Gropius wearing a beret as he plays.

Gropius chose the Lincoln setting because of its proximity to Concord Academy, which his daughter, Ati, attended. Another contribution to his decision to settle there: Gropius’s generous benefactor, Mrs. James J. Storrow (Boston’s Storrow Drive is named after her husband), gave him the site and lent (or perhaps gave) him the money to build the home.

Storrow was so pleased with the result that she allocated house sites and funding to four other Harvard professors as well. One was for Marcel Breuer’s home down the hill from the Gropius House. Alas, this house was rather clumsily modified over the decades and is not open to the public. (I bet the furniture in the home, for at least a while, was amazing.)

Gropius is a legendary figure in the history of architecture but, ironically, he did not complete many buildings. He was much more of a master planner and visionary. Over time, the Bauhaus style has become venerated — a past-perfect image of a utopian future by design. In a very graceful yet practical way, the Gropius House in Lincoln represents the best of the still inspiring and thought-provoking Bauhaus ethos.

Mark Favermann is an urban designer specializing in strategic placemaking, civic branding, streetscapes, and public art. An award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program and, since 2002 has been a design consultant to the Boston Red Sox. Writing about urbanism, architecture, design and fine arts, Mark is contributing editor of the Arts Fuse.

In conversations with a friend, it was correctly pointed out that there were a couple of other “hens’ teeth” built around the same time in greater Boston–The Gibbs House by architect Samuel Glaser in North Brookline, MA (1937) and The Saltonstall House by architect Nathaniel Saltonstall in Medfield, MA ( 1937). Influenced by the Bauhaus aesthetic, they are fine examples of the International Style in the Boston area.

As attractive as a WW2 pillbox.