Film Review: “Amsterdam” — Fast Friends, Broken Bodies, Strong Spirits

By Ezra Haber Glenn

As its plot unfolds, Amsterdam treats us to a strangely magical form of visual and verbal storytelling, both humorous and hard-edged, by turns sweet and shocking, with richly curated frames and bright spirited dialogue.

Amsterdam, directed by David O. Russell. Screening at Kendall Square Cinema and AMC Assembly Row starting October 6.

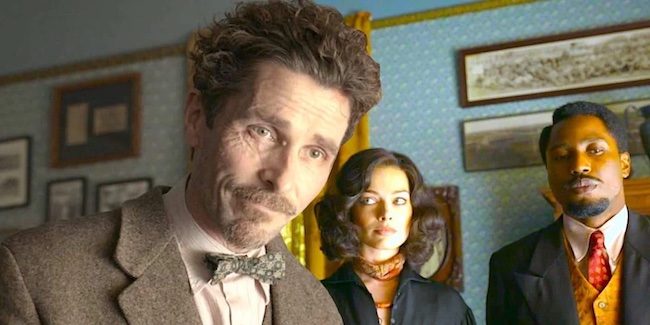

Christian Bale, Margot Robbie, and John David Washington in a scene from Amsterdam.

Amsterdam, the new dark comedy period piece thriller from David O. Russell, is a fun and fulfilling romp through some deep and difficult — at times uncomfortable — corners of our nation’s history. His first offering since 2015’s lukewarm Joy, the film represents a solid, if not unqualified, return to form, a reminder of the witty and freewheeling scripts and well-tuned ensemble work that charmed critics and earned Russell back-to-back Best Screenplay nominations nearly a decade ago for The Silver Linings Playbook (2013) and American Hustle (2014).

Over a swift two-and-a-quarter hours, the film spans two continents and 15 years, striking just the right affective tone to balance the terrible and the absurd, the pointless and the poignant. Similar to much of Russell’s previous work, the script draws on real world events of the “truth is stranger than fiction variety.” The opening title declares — with something of a sly wink — “a lot of this actually happened.” Yet, just as with American Hustle, which mined the 1970s-era FBI Abscam operation for sexy intrigue and farcical comedy gold, here viewers would be wise to leave their fact checkers at home; there is plenty more fiction than fact in Amsterdam. The truth only serves as a convenient point of departure for a modern-day Scheherazade: the fun is not in splitting historical hairs, but in surrendering to the tale as the master spins it out.

(Note for literalists: be warned that Amsterdam is not really about Amsterdam, and only momentarily set there; the story has about as much to do with the title city as Chinatown does with Chinatown, or Fargo with Fargo.)

The setup is surprisingly simple, given how complex and convoluted the path will become by the closing chapters. Following a zippy in medias res kickoff, an extended flashback recounts the formative backstory: two soldiers meet in Europe during the Great War. Burt Berendsen is a chatty but self-effacing half-Jewish, half-Catholic doctor with a medical license and a practice on Park Avenue, all underwritten by his overbearing WASPish in-laws, who have sent him to war to get rid of him (Russell vet Christian Bale, who displays an amazing range and physicality as this lovable, unflappable, broken protagonist, even if he does lean a bit too heavily on a corny accent). Harold Woodsman is a confident and plainspoken Black soldier determined to see his men receive the same respect as their white counterparts, despite the pervasive racism of the Army (John David Washington, stepping further out of his father’s long shadow with impressively understated, nonverbal acting — the quiet sidelong glances, the clipped smile — and some great banter as well). Berendsen — showing a natural affinity to outcasts and troublemakers — agrees to treat Woodsman’s troops with the honor they deserve, and the two form a fast friendship, swearing to stand by each other whatever comes.

Of course, what comes is a load of hell and shit and pain — that is, the War to End All Wars (Part I — although the sequel is ironically teased) — and before the spit is dry on their pact the two are tumbled ass-end up into mud and blood and an army hospital, where the pair becomes a triad: enter Valerie Voze (Margot Robbie), a rich adventuress with a Dada spirit, posing as a French-speaking nurse, who lovingly extracts bushels of shrapnel from both men, which she transforms into shockingly graphic objets d’art. Woodsman and Voze fall quickly in love, with Berendsen as a merry tag-a-long third wheel. The friends spend a magical postwar honeymoon frolicking in Amsterdam. At times it gets a little cloying (including an uninspired “nonsense” song that is more hoke than wit), but it’s hard not to be charmed by the spirit of freedom and gaiety after the horrors of the war.

But eventually the real world intervenes. They’ll always have Amsterdam, but all things must pass, and our flashback fades….

Back in the film’s “present” of Depression-Era New York, Berendsen now runs a makeshift clinic for wounded and disabled veterans, playing fast-and-loose with novel treatments and experimental painkillers, which he often tests on himself. He’s a quack with a heart of gold (and for comic relief: a glass eye that pops out whenever he falls down, which is surprisingly often). Woodsman, now a successful lawyer well-connected to the rich and famous, calls on his old war buddy for a special favor: a rushed autopsy to investigate the suspicious death of their old commanding officer, now Senator Bill Meekins (Ed Begley Jr., hilariously emoting about the same level of energy as both officer and corpse). One bad decision leads to another, and our heroes are soon investigating one murder while under suspicion for another, on the run from a maniacal hit-man, on the trail of a secret society, and entangled in a dangerous conspiracy that runs deep into the dark soul of American fascism.

As the plot unfolds we are treated to a strangely magical form of visual and verbal storytelling, both humorous and hard-edged, by turns sweet and shocking, with richly curated frames and bright spirited dialogue: it’s as if Wes Anderson were called in to direct a mashup sequel to Knives Out and Motherless Brooklyn, co-written by Robert Altman, Umberto Eco, and Guillermo del Toro. Casual (or distracted) viewers may become lost and then frustrated by the sheer number of names, locations, and revelations; there is no good time to sneak out for a bathroom break without missing some important twist. Likewise, more conventional mystery fans expecting a tight coherent narrative may be disappointed by the many holes, ellipses, contrivances, and MacGuffins employed to drive the characters from one impressive set piece to the next. But these are the trees — or maybe just the leaf-debris — not the forest: ignore these deficiencies and there’s a punchiness to the pacing and a soulfulness to the story, driven ever-forward by a sense of fun urgency and nervous verve.

John David Washington, Margot Robbie, and Chris Rock in a scene from Amsterdam.

And bringing it all to life, in the swirl of spirited chaos, are Russell’s characters, and the actors who animate them so well. Each persona is distinct — no small parts or small actors here — and the plotting brings these players together in deliciously sparky combinations. In particular, Chris Rock plays one of the funniest straight men on film, Washington’s right-hand man (no Hamilton reference intended). Hopefully this will invite meatier roles for his deep talents. (With slightly more screen time he would have been an excellent candidate for Best Supporting Actor — it’s his best role since CB4.) Michael Shannon and Mike Myers add comic relief as a Mutt-and-Jeff pair of “wink-wink” spies. And Robert de Niro delivers as well, as always, playing General Gil Dillenbeck, a decorated war hero and perfect Man of Integrity facing a world in moral free-fall. (The character is based on the largest shred of truth behind the film, a Major General with the unlikely name of “Smedley Butler” who helped uncover a conspiracy to overthrow FDR and install a fascist dictatorship.)

Unfortunately, despite having some amazing talent on the female side of the playbill, Russell gives them much less to work with. Beyond Robbie’s Vose, who flirts and dances through both hospital ward and flapper gala with enough energy to counterbalance both male leads, the performances by Anya Taylor-Joy, Zoe Saldaña, and Taylor Swift are uniformly more restrained, almost forced. And, while it’s always risky to speculate, it could be that, in addition to a script pitched more in the bass range, Russell’s directing style itself — which has been called out as abusive in the past, particularly toward women — may have a stifling effect on these excellent actresses, preventing the exploration necessary to fully deliver looser, more freewheeling characters.

Importantly, while the ensemble seems to have lots of fun developing these roles, the characters’ eccentricities and inside gags are amusing but never self-indulgent. The humor bubbles across the screen and pulls us in, creating a shared tableau for the audience to enjoy. Yet it never breaks the frame just to be silly or absurd. In addition, Russell holds this lighthearted tone in check with punctuated moments of crushing and graphic violence: it’s a serious story with a sprinkling of sugar to keep us turning the pages.

Over time, though, the film’s deeper themes percolate and seep through, timely and thought-provoking stuff touching on race and equality; the brutality of war and the evils of eugenics; the true meaning of honor, duty, service, patriotism, loyalty, and friendship; the value of persistence in the face of insanity and indifference; and the heartening ways that wounded bodies continue to house strong spirits that, when called on, oppose seemingly strong bodies with craven souls.

Ezra Haber Glenn is a Lecturer in MIT’s Department of Urban Studies & Planning, where he teaches a special subject on “The City in Film.” His essays, criticism, and reviews have been published in the Arts Fuse, CityLab, the Journal of the American Planning Association, Bright Lights Film Journal, WBUR’s ARTery, Experience Magazine, the New York Observer, and Next City. He is the regular film reviewer for Planning magazine, and member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. Follow him on https://www.urbanfilm.org and https://twitter.com/UrbanFilmOrg.

Tagged: Amsterdam, Christian Bale, David O Russell, Ezra Haber Glenn, John David Washington