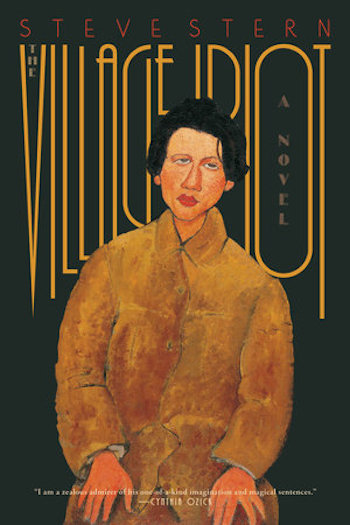

Book Review: Steve Stern’s “Village Idiot” — Painted into a Corner

By Robert Israel

Steve Stern’s novel about the Jewish expressionist painter Chaim Soutine is more informative than it is engaging.

Village Idiot, a novel by Steve Stern. Melville House, NY, 368 pages, $27.99.

As a writer of fiction, Steve Stern’s métier has been to weave Yiddish, the mother tongue of the Jewish people, throughout his stories. He embraces Yiddish and Jewish folklore, drawing, with zest, on his experience of having grown up in The Pinch, a working-class Jewish neighborhood in Memphis, Tennessee. Similar to my hometown of South Providence, Rhode Island, these neighborhoods recreated life in the shtetl (Jewish enclaves) once found bountifully throughout Russia and Europe. Here Jews clustered for safety, communal prayer, and commerce. Yiddish was spoken in the shops, in the synagogues, and in homes. The Holocaust ended that way of life in Russia and Europe. In post-war America, the appeal of assimilation and the strong arm of redlining discouraged long term duplication. In the ’60s, Jews in the Boston area vacated Dorchester and Mattapan for the tonier suburbs of Newton and Sharon. Over time, inner-city Jewish neighborhoods, like The Pinch, vanished, as did the numbers who spoke fluent Yiddish.

As a writer of fiction, Steve Stern’s métier has been to weave Yiddish, the mother tongue of the Jewish people, throughout his stories. He embraces Yiddish and Jewish folklore, drawing, with zest, on his experience of having grown up in The Pinch, a working-class Jewish neighborhood in Memphis, Tennessee. Similar to my hometown of South Providence, Rhode Island, these neighborhoods recreated life in the shtetl (Jewish enclaves) once found bountifully throughout Russia and Europe. Here Jews clustered for safety, communal prayer, and commerce. Yiddish was spoken in the shops, in the synagogues, and in homes. The Holocaust ended that way of life in Russia and Europe. In post-war America, the appeal of assimilation and the strong arm of redlining discouraged long term duplication. In the ’60s, Jews in the Boston area vacated Dorchester and Mattapan for the tonier suburbs of Newton and Sharon. Over time, inner-city Jewish neighborhoods, like The Pinch, vanished, as did the numbers who spoke fluent Yiddish.

Despite that reality, Stern, now a septuagenarian and longtime professor at Skidmore College, is determined to keep the memory of those Jewish-American communities alive. It’s a noble, if perhaps nostalgic, calling. At their best, his narratives echo the tragicomic vision of Yiddish life found in the work of Nobel laureate Isaac Bashevis Singer. And Stern often supplies elements of farce that resonate with the humor in Shalom Aleichem’s short stories. But he is not always successful at tapping gracefully into tradition. His latest novel, Village Idiot, revolves around the life and travails of Russian-born expat expressionist painter Chaim Soutine (1893-1943). The story is set in Paris, and it disappoints.

The encyclopedic weight of the novel’s ambitions flattens the effort. At times, Stern unnecessarily veers away from a fictional recounting of Soutine’s often wretched life; instead, he insists on showing off his considerable research by relating biographical fact. He not only wants to document Soutine’s place among the other artists in Paris, but to also position him, as a Jew and painter, in the era between World War I and World War II. The proceedings become heavy handed because the magic of storytelling is too often banished. What’s called for is a balance between realism and the imagination. Because Stern sticks to the former, Village Idiot becomes more informative than it is engaging.

At the heart of the problem, perhaps, is Stern’s selection of Soutine as his protagonist. Raised in an Orthodox Jewish family in Russia, Soutine endured beatings and starvation until he finally escaped to France. These dire deprivations affected his health and shaped his artistic vision. The late art critic Robert Hughes aptly described Soutine as “an unrelentingly oral painter. In canvas after canvas he seemed to be trying to appropriate his subjects physically, to steal protein from them like an aphid sucking at a leaf.” Stern spends far too much time detailing Soutine’s “aphid” -like appetites. There are endless passages focusing on Soutine’s horrific stomach ulcers and worse, his woebegone misadventures in the bedroom. There are tiresome scenes in brothels with Soutine’s pal, the Italian Jewish expat painter Modigliani. Sentences like the following appear throughout Village Idiot: “His scrotum and spine are elevated as if by an electrical charge. Astonished at this development, Chaim cries out, ‘We’re shtupping (copulating)!’ and, transported by her heat, further qualifies, ‘It’s good!’” As erotic play-by-play this is, to be kind, maladroit.

Besides, hanging out in the lower rungs of Paris has been done before by others, and done better. British author George Orwell brought his journalist’s skill to his 1933 novel Down and Out in Paris and London. The book unflinchingly observes the depths of depravity, disease, and drunkenness wallowed in by the hoi polloi. American author Henry Miller followed a year later with his novel (banned for obscenity) Tropic of Cancer: it is also set in Paris and broke new ground by dramatizing the sensual (and ethical) freedom experienced by men running amok with prostitutes.

So Stern breaks no new ground here. In truth, he fails to convince the reader why Chaim Soutine deserves our attention, whether he is in a house of ill repute or elsewhere. I’m also at a loss to understand — or appreciate — Stern’s strong suggestion that the artist should be seen as an exemplary Jew. Perhaps, in his next novel, Stern should stick to familiar American turf, such as The Pinch.

Robert Israel can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.