Book Review: A Well-Written Biography of Stewart Brand — The Man Who Popularized Planetary Consciousness

By Preston Gralla

Stewart Brand’s greatest achievement, by far, was the simple act of putting the photograph of the earth as seen from space on the Whole Earth Catalog’s cover.

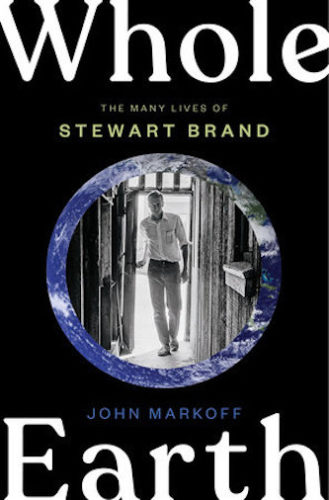

Whole Earth: The Many Lives of Stewart Brand by John Markoff. Penguin Press, 416 pages, $32.

Most people who helped transform life and thought in the mid-20th to early 21st century have been associated with a single movement: Rachel Carson pioneering the environmental movement, Timothy Leary and Ken Kesey cheerleading for psychedelics, Steve Jobs helping launch the personal computer revolution.

Most people who helped transform life and thought in the mid-20th to early 21st century have been associated with a single movement: Rachel Carson pioneering the environmental movement, Timothy Leary and Ken Kesey cheerleading for psychedelics, Steve Jobs helping launch the personal computer revolution.

The lesser-known Stewart Brand was in the forefront of all of that and more. He served as a bridge between the Beats and the hippies, became a fellow traveler of Kesey, and helped organize and promote the Trips festival in 1966 in San Francisco that catalyzed the psychedelic counterculture. He created the Whole Earth Catalog, the bible of the back-to-the-land movement that helped turbocharge environmentalism. Founder of the influential early online community The WELL (Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link), he coined the phrase “Information wants to be free” and became the godfather of the early, idealistic phase of the tech movement.

Now, finally, he is the focus of an overdue biography, Whole Earth: The Many Lives of Stewart Brand by the well-known technology journalist and author John Markoff. It’s well-written, encyclopedic, and readable, far more than a just-the-facts replay (and there’s plenty to replay) of Brand’s life to date. (Brand is 83 as I write this.) Markoff’s analysis of Brand’s influence and motivations, warts and all, is superb. If you’ve never heard of Brand and want to learn more about our current cultural moment, you owe it to yourself to read it. And if you think you already know enough about Brand, you have even more reason to read it, because you don’t know half of what he’s done, and probably will be stunned by his current incarnation.

Markoff covers Brand’s journey, his start as a golden boy (Midwestern WASP version) educated at Exeter and Stanford. Brand had titanic energy and titanic ambition, but for much of his young life struggled to find the right vessel for it. When he graduated from college as a biology major in 1960, he couldn’t decide whether to become a journalist or a biologist. Instead, he joined the Army, but soon came to hate its strictures and suffocating bureaucracy. After his time was up, he settled in San Francisco, and adrift, took photography classes at the San Francisco Art Institute.

In San Francisco he discovered his genius for making connections and riding the wave of what was culturally new. He made his way to the fringes of the Beat movement and from there into Ken Kesey’s circle. Soon he was friendly with a who’s who of the ’60s counterculture, living not far from several members of the Grateful Dead and various Kesey Merry Pranksters. He helped organize and publicized the Trips Festival that helped launch the psychedelic movement and counterculture. He organized other events that highlighted speakers and performers including Allen Ginsberg, Joan Baez’s sister Mimi Fariña, and Wavy Gravy, who later gained fame by using his commune the Hog Farm to feed hundreds of thousands of people at Woodstock.

At the same time, he became deeply involved with the earliest personal computer pioneers at Stanford, including Douglas Englebart, whose work was a forerunner of the World Wide Web, the Apple Macintosh, and other groundbreaking technologies.

Unknown to most people, though, he was an odd fit for the counterculture. Markoff writes that at heart Brand was an apolitical libertarian and a critic of the New Left and antiwar movement, so much so that at one point he was gleeful because Ken Kesey sicced the Hell’s Angels on antiwar protesters.

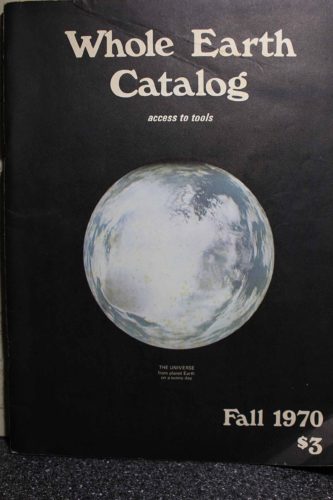

It wasn’t until launching the Whole Earth Catalog in 1968 that he truly found his calling and made his greatest mark. Just its cover — one of the first colored pictures of the entire Earth as seen from outer space — helped launch the environmental movement by showing how interconnected the planet is. It wasn’t a single catalog, but rather a series of them, listings of what Brand called “access to tools and ideas.” Essentially the Sears catalog for the back-to-the-land movement, it listed places to buy gardening and farming tools, metalworking equipment, potters’ wheels, windmills, early personal computers, and more. Steve Jobs, in a 2005 Stanford University commencement speech, likened it to being the Google of its time.

It wasn’t until launching the Whole Earth Catalog in 1968 that he truly found his calling and made his greatest mark. Just its cover — one of the first colored pictures of the entire Earth as seen from outer space — helped launch the environmental movement by showing how interconnected the planet is. It wasn’t a single catalog, but rather a series of them, listings of what Brand called “access to tools and ideas.” Essentially the Sears catalog for the back-to-the-land movement, it listed places to buy gardening and farming tools, metalworking equipment, potters’ wheels, windmills, early personal computers, and more. Steve Jobs, in a 2005 Stanford University commencement speech, likened it to being the Google of its time.

Markoff sums up its influence this way: “The Catalog would shape the worldview of an entire generation of young Americans, key engineers and entrepreneurs in what would soon become Silicon Valley and would presage the ’70s environmental movement.”

The appeal of the back-to-the-land movement eventually faded, and Brand soon rode the Next Big Thing, technology. In 1985, he founded The Well (Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link), an early influential for-pay online community that prided itself on being a salon where people could share and debate Big Ideas. Steve Case was a member before founding AOL, as was Craig Newmark before he went on to found Craig’s List. As influential as it was, however, much of The Well’s funding didn’t come from big thinkers but from avid Deadheads, who flocked to it as a kind of Grateful Dead Information Central.

He also organized the Hacker’s Conference (in those days, the word hacker referred to anyone with hands-on proficiency with technology), which brought together programmers and hardware makers, including Apple’s Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, free software proponent Richard Stallman, and many others. At the first conference, Brand coined what became the call to arms of the early idealistic days of tech, the Internet, and the Web: “Information wants to be free.”

Markoff points out what’s been forgotten now: Brand offered a more nuanced view of the motto than others at the conference, explaining, “On the one hand, information wants to be expensive because it’s so valuable.… On the other hand, information wants to be free because the cost of getting it out is getting lower and lower all the time. So you have these two fighting against one another.”

Brand soon abandoned that nuance, though. He became a cheerleader for tech, a professional optimist who believed only good would come of its increased use. He saw no dark side to it at all.

Just consider what he told a journalist back then about the potential dangers of no-limits, unfettered online communication: “Computers suppress our animal presence. When you communicate through a computer, you communicate like an angel.” He also belittled the idea that dangerous hackers might cause real harm, because “white hat” good-guy hackers would always better them.

As we know now, he couldn’t have gotten it more wrong.

Brand became a visiting scholar in MIT’s Media Lab, aptly described by Markoff as “a research center at the intersection of engineering, social science, and the arts,” then wrote a bestselling book about it, The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT. Garnering that imprimatur as a futurist, he pivoted to become a corporate consultant, notably to the massive oil company Royal Dutch Shell, among others. Fortune magazine profiled him in an article titled “The Electric Kool-Aid Management Consultant.” He’d come a long way from helping hippie homesteaders build windmills.

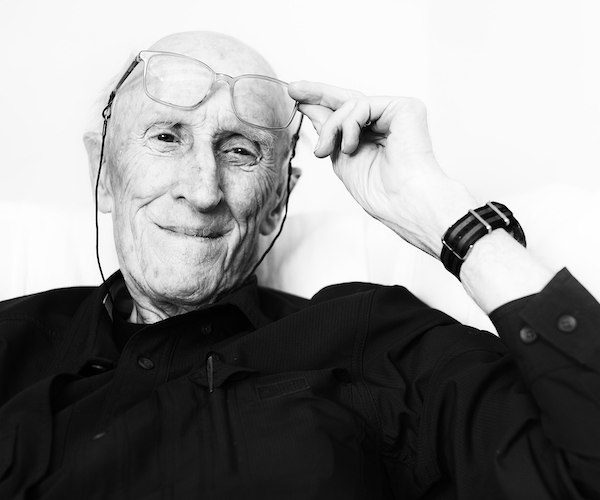

Stewart Brand at his Sausalito office in 2020. Photo: Christopher Michel

So far, in fact, that he wrote in his personal journal that much of what defined the ’60s counterculture that he helped create was flat-out wrong, including “drugs, communes, spiritual practice, New Left politics, solar water heaters, domes, small farms, free schools, free sex, on and on.” He apologized to himself for helping promote them, writing in his journal, “my bad.”

As his cultural influence waned, he put together a proposal for a book titled “How to Be Rich Well.” In the proposal, he highlighted his insider access to friends among the super-wealthy, including, among others, multiple Rockefellers, William Randolph Hearst III, Jeff Bezos, Sergey Brin, Larry Page, Steve Jobs, and “possibly the Duchess of Devonshire,” whoever she might be.

What exactly would be in the book? Here’s some of what he suggested in his outline: “Managing luxury is a huge and tricky issue, worth a couple of chapters, ranging from the burden of multiple houses to the lethality of helicopters.”

Apparently the perils of the rich, such as worrying about being killed by their aerial transportation or finding the right managers for their many homes, was not considered all that appealing. Not a single publisher bit. Eventually Brand wrote the book Whole Earth Discipline, which touts nuclear power as the answer to global warming. He also believes geoengineering on a large scale is required as well.

It’s a tribute to Markoff’s book that what appears to be a radical about-face comes off as almost inevitable, given his portrait of a man who believed, above all, in the ability of tools to solve our problems. Brand’s credo is that we just need to tinker with what exists rather than changing the flawed systems. As for his attitude toward money, it shouldn’t be a surprise. Markoff writes that his way through life was eased by a trust fund that supported him when he needed it. He tapped into it to launch the Whole Earth Catalog.

Given such an eventful and complicated life, what has been Brand’s most important contribution to the world and culture? From my point of view, it’s not the work for which he is best known, the Whole Earth Catalog. The catalog proved to be less a transformative how-to manual aimed at those desiring to head back to the land than it was a virtue-signaling coffee table book for latter-day Marie Antoinettes and Marc Antoines pretending to take on the roles of shepherds and shepherdesses.

As for the WELL and his tech adventures, they were essentially a sideshow. The tech revolution proceeded on its own problematic trajectory. He didn’t change it at all. And he was thoroughly blind to the big issues that need to be confronted if we are going to master tech rather than having it master us.

His greatest achievement, by far, was the simple act of putting the photograph of the earth as seen from space on the Whole Earth Catalog’s cover. That single image, by itself, had a tremendous impact on the way we all see the world. That visual made a lasting impact. Markoff aptly writes, “Briefly in vogue in the ’70s, the notion of ‘planetary consciousness’ is an idea that Brand’s work first provoked in the ’60s. A half-century later, it remains his signature contribution.”

Preston Gralla has won a Massachusetts Arts Council Fiction Fellowship and had his short stories published in a number of literary magazines, including Michigan Quarterly Review and Pangyrus. His journalism has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Dallas Morning News, USA Today, and Boston Globe Sunday Magazine, among others, and he’s published nearly 50 books of nonfiction which have been translated into 20 languages.

Tagged: Preston Gralla, Stewart Brand, Whole Earth Catalog, john markoff

Thanks for such a smart, comprehensive overview of Brand. Thanks, Preston.I do wonder a bit at Markoff’s point of view and whether it veers from your own. I don’t find it surprising that a libertarian found a place in the New Left hippy movement. Kesey to me is a libertarian also, not a left-winger. Nor are, for example, Kerouac and Burroughs. And I would add one adjective to the description you approve of the MIT Media Lab: “a CORPORATE-FINANCED research center at the intersection of engineering, social science, and the arts,”

Good point about adding that adjective to the Media Lab; the lab’s heavy corporate connections are often forgotten or ignored in media coverage. I also agree about Kesey and Kerouac not being left-wingers; Kerouac ended up a right-winger, though I’m not sure if he started that way.

Markoff tried to play it down the middle and was careful not to overtly add his point of view. He didn’t make much of Brand as being what we would call now a trust-fund baby, and he was straightforward in portraying what appears to be Brand’s eventual total about-face. But to do otherwise would be gilding the lily, the facts spoke for themselves and needed no embellishment.

Excellent review Preston.

I am looking forward to my next read thanks to you.

Bruce