Visual Arts Review: Otto Piene’s Sketchbooks at the Harvard Art Museums

By Mark Favermann

MIT’s loss is Harvard’s gain.

Processing the Page: Computer Vision and Otto Piene’s Sketchbooks on view from July 5 to 31.

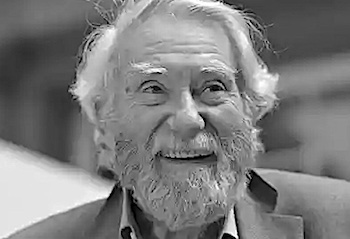

Portrait of Otto Piene in 2012. Photo: Michael Gottschalk/Photothek

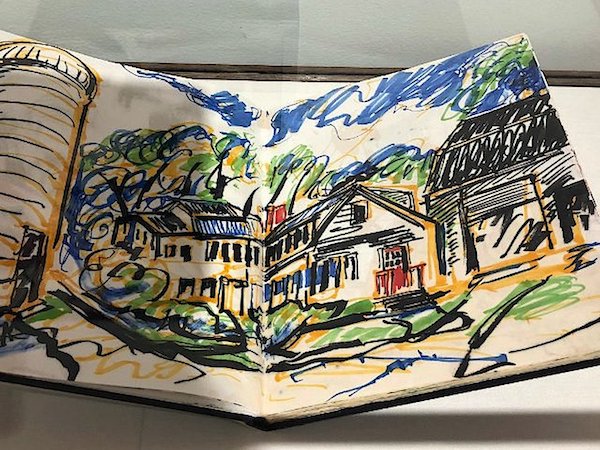

Currently on view is an interactive installation at Harvard Art Museums’ Lightbox Gallery that features artist Otto Piene’s vivid and insightful sketchbooks. Created over seven decades, they illustrate how a world-class artist perceived and visualized his creative process.

This recent gift to the Busch-Reisinger Museum includes more than 70 sketchbooks kept by artist Otto Piene (1928–2014). They were donated by his widow, artist Elizabeth Goldring. Dating from 1935 to 2014, the largely unpublished sketchbooks are examples of the interdisciplinary, cross-media experiments Piene envisioned over the course of his long creative career. The sketchbooks include both realized and unrealized projects and draw on Piene’s passionate interest in optical perception, artistic lighting, and kinetic forces.

The diverse themes and approaches in Piene’s sketchbooks reflect his interest in the intersection of art, technology, and the natural environment. Each of the volumes is itself an art object — a portable studio, a record of visual thinking, an imaginative platform space for material experimentation. Piene could, when asked, elegantly articulate (in German and English) his artistic goals, but he felt strongly that art came out of the practice of art. His sketchbooks gave agency to his creative process.

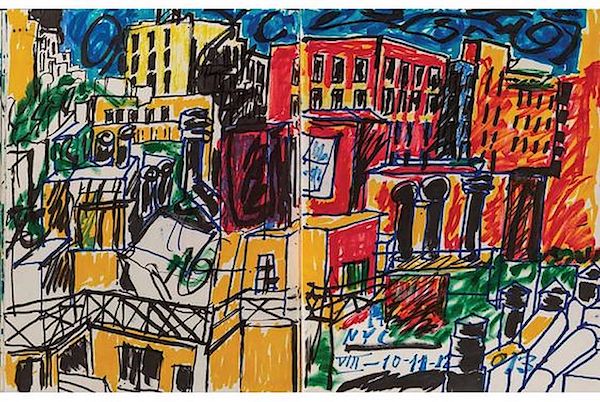

Filled with bold expressionistic drawings, the sketchbooks are both pictorially appealing and instructive. Piene’s early pictures (from childhood) show a fascination with as well as a fear of technology. He continued drawing throughout his life and, according to Goldring, he brought sketchbooks everywhere they went — including on vacations, on trips, and even to and from MIT, where he taught. Whenever he had a few minutes he would sketch, and his visions are layered in interesting ways — personal, yet impersonal, not anecdotal but universal.

Piene spoke about the value of collaboration, but his environmental work depended on finding other artists to assist in making them a reality. Technical work on his projects was inevitably carried out by long-involved, highly skilled experts. He was always the Maestro, the Distinguished Conductor. His work was always at the center of his efforts. In no way does this egotism diminish his art or his work’s cultural significance.

Examining over 9,000 sketchbook pages, Jeff Steward, the museum’s director of digital infrastructure and emerging technology, and Lauren Hanson, the Stefan Engelhorn Curatorial Fellow in the Busch-Reisinger Museum, have uncovered various hidden narratives, which add to our understanding of Piene’s creative consciousness. Adroit experimentation with human and AI-generated data gives gallery visitors an opportunity to browse Piene’s digitized sketchbooks by using either an iPad stationed in the gallery or their own smartphone. A digital resource that will provide open access to the museums’ full collection of Otto Piene’s sketchbooks will be launched in late August.

Two page spread from Otto Piene’s Sketchbooks. Photo by Astrid Hiemer, 2019

Aside from his artistic pursuits, much of Piene’s time was taken up as a professor at MIT and the director of its Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS; 1974-1994). The center was founded in 1967 and its mission was to bring art into contact with contemporary scientific as well as technical research and practice. The founding director of the Center was the courtly Hungarian/American artist György Kepes (1906-2001). CAVS had been inspired by the example set by earlier Bauhaus and Black Mountain College artistic educational experiments. But there were substantial differences. CAVS saw itself as an academic research center for art, science, and technology. Kepes envisioned CAVS as an institutional creative forum that would underscore how art and science complemented each other via trans-disciplinary collaborations.

In 1968, Piene was the first international Fellow at CAVS, and in 1974 he went on to succeed Kepes as director until his retirement in 1994. Previously, Piene was one of the founders of the international artist group ZERO. In the ’60s and ’70s, Piene became a pioneering figure in multimedia and technology-based art, celebrated for his smoke and fire paintings and environmental “sky art” installation pieces.

Describing the interaction of art and technology in a creative collaborative project, Piene saw the scientist as adding a “brain,” the engineer adding an “arm,” and the artist adding an “eye.” Most but not all CAVS artist projects were conceived and installed in urban open spaces. Their temporary and/or site-specific art works were generally installed in building lobby interiors, plazas, parks, stadiums, and riverbanks. Piene inhabited CAVS with artists that worked with a wide variety of media and methods, including video, lasers, holograms, music & tone, steam, sundials, light, kinetics, projections, robotics, and inflatables.

NYC sketch by Otto Piene. Image courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

Unfortunately, during Piene’s tenure a restrictive rule at MIT’s List Visual Art Center prohibited the exhibition of CAVS artists’ works — no doubt yet another outrageous example of academic institutional pettiness. That wrong was finally righted in 2011, when Piene’s art was finally displayed there. And even though over the decades Boston became an international center for art and technology work — thanks in a major way to CAVS — the venerable Boston Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) and the (often) opportunistic Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) showed little or no interest in Piene’s work or in emerging work that interlaced art and technology. This neglect became all the more embarrassing because his projects have been included in nearly 200 museums and public collections around the world. Here is a sampling: the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Nationalgalerie Berlin; the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Piene lived and had studios in Groton, Massachusetts, and Düsseldorf, Germany.

In 2009, CAVS and the Visual Arts Program were integrated into the MIT Program in Art, Culture, and Technology (ACT). The upshot of this institutional move is that, sadly, CAVS disappeared. In 2018, an indifferently curated and disappointing exhibit at the MIT Museum — Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the MIT Center for Advanced Visual Studies at the MIT Museum — lacked thoughtful historical context as the selected works competed against each other for attention. To some extent, the history of CAVS can now be surveyed via the C.A.V.S. Special Collection at MIT. Unfortunately, this is a limited, narrowly selected group of works and papers that leaves out important creative contributions by a number of other CAVS artists. Oddly, Piene’s wonderful sketchbooks are not part of the CAVS Special Collection. MIT’s loss is Harvard’s gain.

Mark Favermann is an urban designer specializing in strategic placemaking, civic branding, streetscapes, and public art. An award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program and, since 2002 has been a design consultant to the Boston Red Sox. Writing about urbanism, architecture, design and fine arts, Mark is contributing editor of the Arts Fuse.

Tagged: Busch-Reisinger Museum, CAVS, Center for Advanced Visual Studies, György Kepes, Harvard-Art-Museums, Mark Favermann, Otto Piene, Processing the Page: Computer Vision and Otto Piene’s Sketchbooks, art

Otto Piene and a number of CAVS fellows were included in the MFA’s singular, and never repeated Elements (Elements of Art: Earth, Air, Fire, Water, 1971,) an exhibition curated by Virginia Gunter. Soon after Ken Moffett was appointed as contemporary curator and lost interest in issues of Art Science and Technology. The ICA, then and now, has shown little interest in this local activity through MIT’s CAVS that was embraced globally. Centerbeam for Documenta is but one stunning example. My wife Astrid HIemer, in many capacities., assisted Otto for two decades. Our colleague and friend Mark Faverann makes a compelling case for this major archive being made available at Harvard. Otto worked until the end. Poetically he died in a cab in Berlin on the way to what proved to be his final exhibition. Other than his role in Elements I curated his only Boston exhibition, a selection of large drawings, for the New England School of Art and Design.