Visual Arts: My Main Man Mani — A Persian Preacher Who Made Art and Founded a Religion

I have a weakness for cosmic audacity. The history of religions, which I studied before art history, is full of examples that give me a deep inner thrill.

By Gary Schwartz.

Kabbalists who use their mystic powers to force the coming of the Messiah—to strong arm God himself—can count on my all-out support, despite the potentially unpleasant consequences for myself if they succeed. The Maharal, Yehudah ben Betzalel Löw (ca. 1525–1609), who lived in the Prague of my fellow fan of over-the-top chutzpah Emperor Rudolf II, is said on good authority to have vied with the creator by instilling life into a clay figure, a golem. Wow! Israel is chalked and plastered with graffiti and posters beginning Na Nach Nachma, an invocation of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov (1772–1810), who coquettishly suggested to his followers that he might be the Messiah.

One of my heroes is the Persian preacher Mani (ca. 210–276), the founder of a religion that came to be called, after him, Manichaeism. Mani claimed to be the Holy Ghost incarnate, come into the world to knit the teachings of Jesus, Zarathustra, Buddha, and other worthy predecessors into a single all-encompassing belief. He succeeded in creating a faith that was practiced for a thousand years from North Africa to China and that wherever it went influenced the mainstream religions that repudiated it violently. Mani took the existence of evil more seriously than most of us and refused to burden the good Lord with responsibility for it. He split creation into dual halves, with the forces of light engaged in eternal struggle with those of darkness.

The history of art has some rash characters, like Caravaggio or Marcel Duchamp, and some even rasher ideas about what art is about. Giorgio Vasari, one of the fathers of art history itself, calls God the first artist and claims semi-divine status for the creative artist. But this is no-risk rhetoric, not like storming the doors of heaven, which got Mani into the Persian prison where he was martyred.

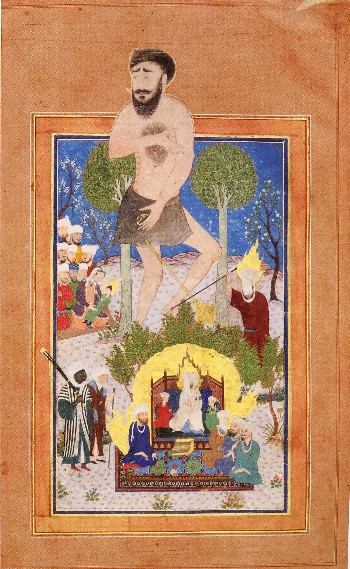

The giant 'Uj and the prophets Moses, Jesus and Muhammad, Tabriz, early 15th century. Khalili Collection

Imagine my delighted astonishment, then, when I found out, an embarrassingly short time ago, that according to Persian tradition, Mani was a painter, a serious professional artist. Moreover, he combined his preaching with his art by spreading his message in the form of wall paintings and illuminated scrolls. When Mani received divine revelation, it came to him not in the form of carved tablets or of the Word but in a book of pictures that he always had with him, the Ārzhang. What style did this master of light and dark call his own? What is the look of Manichaean chiaroscuro?

Until recently, the literature said that none of Mani’s paintings has survived. However, the Japanese Indologist Yutaka Yoshida now claims to have discovered in a Japanese private collection later versions of Mani’s dizzying images of the cosmos and the soul (With kind thanks to Shaul Shaked for leading me to this treasure.) Be this exciting possibility as it may, in the Safavid Persia of the 17th century, painters could still be praised as The New Mani, while in keeping with his controversial character he is referred to by other Persian writers on art as a model to be avoided—but a model.

Mani plays a role in the introduction to the magnificent book on the collection of Islamic art assembled over the past 40 years by Nasser David Khalili. His significance in a discussion of art in Islam lay in his reputation for lifelike illusionism. Antipathy to realistic images of humans may have been a recurrent strain in Muslim theology, but it was not always honored in the observance, and Mani was a legendary master of the mode. In the 13th century, the Persian poet Nizami told with approval this story about him. Entering China to preach and paint, he was awaited by the Chinese with murderous intent. When he left the desert he came upon what looked like a pool, but when he tried to scoop water out of it with his crock, it broke on the surface of what turned out to be a sheet of crystal formed to resemble a body of water. Mani responded, to protect other travelers, by painting on the crystal a powerfully illusionistic image of a dead dog, his stomach open and crawling with worms. The Chinese were impressed and were sporting enough to open up their country to him and his mystic dualism.

Highlights from the Khalili collection of Islamic art (he has a number of other important collections as well) are on view until mid-April in the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam. The collection is astonishing, all the more so since it was built up only over the past 40 years. Khalili, an Iranian Jew who lives in London and the U.S., is not only an accumulator. He partakes in extreme measure of another characteristic of many collectors, the urge to share his treasures with the world. Parts of his Islamic collection of Qu’rans, metalwork, pottery, glass, sculpture, manuscripts, carpets, textiles, arms and armor, enamels, lacquerwork, jewelry, and whatever else comes his way has been exhibited more than 10 times in museums around the world. He is also publishing his collection in a series of fundamental catalogues.

Manichee ecumenism is contagious. Khalili himself is an admirable prophet of interfaith activism, which he propagates through the Maimonides Foundation. He also shares Mani’s faith in the universality of art. At a public interview in the Nieuwe Kerk on March 3rd, he proudly projected what he called the only known Islamic miniature depicting the founders of the three religions of the book: Moses, Jesus and Muhammad, beneath the giant ‘Uj. Waving his arm into the nave of the medieval Dutch church where the exhibition is being held, he claimed for art the power to bind believers of all faiths. “Here is Islamic art collected by a Jew being displayed in a Christian church.”

Sadly, you don’t have to be an xenophobe from the dark side to harbor doubts. Why is Khalili’s miniature the only one in Islamic art to pay equal respect to the three Abrahamic religions? Where are the respectful Christian and Jewish depictions of Muhammad? Let’s look at the question again when an Islamic collector shows his Jewish and Christian art in a mosque. If this never happens, it won’t be because Khalili didn’t give it his best try.

Khalili paid the Nieuwe Kerk, its director Ernst Veen, and the designer of the current exhibition, Siebe Tettero, a great compliment by saying that it is the most beautiful of all the showings of his collection. I can believe it. The use of glass and mirrors is magical without being willful. Many displays are contained in compartments bounded by mirrors, creating a seemingly vast space for them alone. The visitor sees himself in touch with the art. Vaut le voyage.

For an accessible one-volume presentation of highlights from the Islamic collection, see J. M. Rogers, The Arts of Islam: Masterpieces From the Khalili Collection, London (Thames & Hudson) 2010. ISBN 978-0-500-51534-9

The square before the Western Wall, with an Ethiopian chassid among thousands of worshipers and partygoers, mainly young Israelis in and out of uniform. Another forbidden cell-phone snapshot by the author.

Two weeks ago, on Friday evening the 18th of February, I found myself at the ultimate tri-faith location, the Old City of Jerusalem. On Sabbath Eve, at the foot of the platform on which stand the Dome of the Rock and the Al Aqsa mosque, one of the faiths, Judaism, monopolizes the scene. Atop the wall is the Muslim Haram al-Sharif, which during prayers is reserved to Muslims. A few hundred yards into the Old City is the Via Dolorosa, the Holy Sepulchre, and other Christian locations, open to all. Each of the religions is divided into subdenominations on uneasy terms with each other. It is to be hoped that Nasser David Khalili’s dream of peace between them all will some day come true. In the meanwhile, art is a great consolation.

© Gary Schwartz 2011. Published on the Schwartzlist on March 7 2011.

Gary Schwartz was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1940. In 1965 he came to the Netherlands with a graduate fellowship in art history and stayed. He has been active as a translator, editor, and publisher; teacher, lecturer, and writer; and as the founder of CODART, an international network organization for curators of Dutch and Flemish art.

As an art historian, he is best known for his books on Rembrandt: Rembrandt: all the etchings in true size (1977), Rembrandt, his life, his paintings: a new biography (1984) and The Rembrandt Book (2006). His Internet column, now called the Schwartzlist, appeared every other week from September 1996 to April 2007 and has been appearing since then irregularly. His most recent book on Rembrandt is one of the six titles nominated for the Banister Fletcher Award for the most deserving book on art or architecture of that year.

In November 2009 Schwartz was awarded the coveted tri-annual Prize for the Humanities by the Prince Bernhard Cultural Foundation of Amsterdam.

Please address reactions to Gary.Schwartz@xs4all.nl

Why is Khalili’s miniature the only one in Islamic art to pay equal respect to the three Abrahamic religions? Where are the respectful Christian and Jewish depictions of Muhammad?

It’s my understanding that part of the reason is that Moses and Jesus are not necessarily seen as prophets of Judaism and Christianity, but as prophets of Islam who were misinterpreted by the Jews and Christians respectively.

As far as Jewish representational art: up until the 19th century or so, the prohibition of pictorial representation of the human form was perhaps even more pronounced in Judaism than it ever was in Islam.