Film Commentary: Three Amazing Movies Turn 50

Compiled by Bill Marx

Critic Ed Symkus opened the door when he praised films from “three bona fide innovators, three singular directorial voices” released in 1972: Ken Russell’s Savage Messiah, Bob Rafelson’s The King of Marvin Gardens, and Brian De Palma’s Get to Know Your Rabbit. Other Fuse critics contacted me, wanting to sound off on their favorites from that year. They clamored to have their say, so what is an intimidated editor to do? Here are more celebrations of significant films that are turning 50 this year. And it is a terrifically eccentric trio: Marjoe, Pink Flamingos, and Silent Running. The unruly Tim Jackson also slips in a few other titles.

— Bill Marx

Marjoe Gortner undertaking some spiritual healing in 1972’s Marjoe.

Marjoe

1972 was a year of transitions and extremes. Weary from a long and waning war, boomers desired movies that not only reflected their values but were aware of the new cinematic visions in Europe. The bottom line: they wanted movies that challenged free expression, for better or worse. Pink Flamingos secured John Waters’s reputation as the Pope of Trash and pushed bad taste to new heights — or lows. Edith Massey as the Egg Lady mother to Divine’s Babs Johnson cries from her playpen, “I’m starving to death. Please Babs, come and bring me some eggs.” That screech of “Eggs, Eggs, Eggs” continues to haunt my dreams, along with the coup de grâce featuring Divine, a dog, and a small turd. (See Nicole Veneto on Pink Flamingos below)

The title of Roman Polanski’s film, What? begs its own question. The movie was a kind of Alice in Acid-land sex-romp that popped up after Rosemary’s Baby and Macbeth and before the masterpieces Chinatown and The Tenant. Among What?‘s many jaw-dropping moments: Marcello Mastroianni donning a tiger costume in order to be flogged by the often-naked starlet, Sydne Rome.

25 years before James Cameron re-sank the Titanic, Irwin Allen, a master of disaster schlock, produced The Poseidon Adventure. A few steps down the bottom rungs, football great Rosey Grier and 72-year-old Academy Award winner Ray Milland were stuffed into a capacious body suit to play The Thing with Two Heads. At the bottom of the exploitation ladder (or top, depending on how you judge these things), there was Blood Freak. It took two directors, Brad F. Grinter (Flesh Feast) and Steve Hawkes, to give birth to this incomprehensible combination of anti-drug message and gore. One character eats tainted meat, grows a turkey head, and becomes addicted to blood. It was also Veronica Lake’s last film appearance. (It can be seen on the Internet Archive)

On the top of the cinematic ladder there were controversial achievements, such as Last Tango in Paris. Beautiful as the film is, today its once edgy eroticism feels forced. The notorious “butter scene” was a last-minute improvisation suggested by director Bernardo Bertolucci. That episode remains infamous decades later; co-star Maria Schneider never spoke to Bertolucci again. The Italian director did, however, push Brando into contributing some hauntingly personal monologues. Meanwhile, Werner Herzog pushed Klaus Kinski, another actor of overwrought intensity, to the brink of insanity in Aguirre, Wrath of God. In A Guide for the Perplexed, a collection of conversations with the filmmaker, Herzog comments “I knew his reputation, that he was probably the most difficult actor in the world to deal with: working with Marlon Brando must have been like kindergarten in comparison.”

One actor who who should not be overlooked is Marjoe Gortner. He performed brilliantly, as himself, in the documentary Marjoe, the story of an evangelical showman who was made to embrace the calling at the age of three-and-a-half.

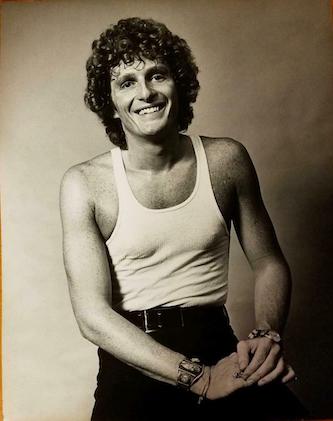

A 1972 publicity photo for Marjoe.

This film, from Village Voice writers Howard Smith and Sarah Kernochan, won the 1972 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. Gortner’s first name was a combo of Mary and Joseph. It was he who contacted the filmmakers with a request to follow him throughout 1971. The goal was to shed light on how evangelical preaching was a lucrative swindle. There was predictable resistance to an exposé of bible-thumping. According to Kernochan, “the distributor refused to open it in any city south of Des Moines.”

The original print was somehow damaged and disappeared until a pristine negative was rediscovered and released on DVD in 2005. The presence of the film crew is part of the doc’s dissection of the showbiz dynamic. Marjoe tells them what to expect and how to behave while shooting: “They’ll trust you because I brought you and they believe in me.” In one scene we watch Marjoe as he sits, cross-legged and bare-chested, counting piles of money: it is the night’s take from a sermon that had left worshipers falling, laughing, shaking, and crying. To the camera, he casually discusses his training and costuming as child: “My mother would sew extra pockets in my suit so I could stuff money. They’d announce, ‘Everyone tonight who gives $20, little Marjoe will come down and give you a kiss. And all these lovely old ladies wanted to put their fingers in my little curly locks — I’d come back and my father would alleviate me of the money.” His parents had exploited him for years — Marjoe didn’t believe a word of what he was preaching. In an archival clip at the start of the film, Marjoe’s mother declares, “All across the nation for the last four years, the little creature has been going up and down winning lost humanity with the message of the master.”

Most of the crowds are white. There is a single service with a Black audience and you can see a distinct difference. The dancing feels more celebratory, less possessed; the music and the singing of the chorus is positively joyful. There are more smiles and fewer tears.

With his tan good looks and halo of curly blond hair, Marjoe was Billy Graham in the guise of Mick Jagger. Like Jagger, Marjoe was a charismatic performer, deft at his craft. He also had some respect for his followers, despite believing that “they’re a little weird.” He speaks without bitterness or anger in the documentary. “It’s not necessary to look for some person to get you off and to put your belief in. Religion is like a drug,” he explains at one point. Marjoe ends up being more of a confessional than a critique: time spent at revival meetings is interspersed with Gortner neatly describing the tricks and illusions of the God trade. I love the immersion. In 1972, for a white kid from Connecticut, this world was both mesmerizing and comical. 50 years later, in a more culturally divided America, the cult-like atmospherics feel much more threatening. The film makes no judgments. You decide.

— Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story, and the short film The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.

Pink Flamingos

The cast of Pink Flamingos. Front row, left to right: Divine/Babs Johnson (Divine), Connie Marble (Mink Stole), and Mama Edie (Edith Massey). Back row, left to right: Cotton (Mary Vivian Pearce), Crackers (Danny Mills), writer/director John Waters, and Raymond Marble (David Lochary). Photo: Lawrence Irvine/Fine Line Features

A couple months back when I reviewed the newest Jackass movie, I noted the queer cultural throughline tying Johnny Knoxville and co.’s juvenile hijinks to the cinematic depravity of John Waters and the Dreamlanders. I ended up going on a Jackass and John Waters bender for the next couple of weeks, revisiting the other Jackass movies (as well as the television series) and finally watching Waters’s last feature, 2005’s A Dirty Shame, starring Knoxville, to assuage any lingering seasonal depression. Though Waters has no plans to return to filmmaking any time soon, 2022 marks a monumental year for the Pope of Trash; to celebrate Pink Flamingos’ 50th anniversary, Criterion is releasing a brand new 4K restoration of the film in June that I’ll probably replace my second-hand DVD copy with. Long familiar with Flamingos’ reputation as one of the grossest movies ever made, I bought said copy from a comic book store in 2019, immediately went home to watch it, and according to my Letterboxd entry, I gave it four out of five stars for being “just fucking disgusting.”

None of that disgust wore off upon recent rewatch, but the shock value has given way to just being flat out funny to me, like I’m in on an inside joke. Even the nastiest bits are punctuated with comical line deliveries (especially Cracker’s “Hold these goddamn chickens!” and “Do my balls mama!”) and a sense of absurdism so pure it veers into childlike innocence (crib-bound Edith Massey’s love of eggs is strangely wholesome in a movie where a man’s asshole whistles along to “Surfin’ Bird”). Pink Flamingos still plays as a fucked up and unapologetically queer satire on the nuclear family, an exercise in bad taste dedicated to assaulting moral puritanism and polite society by violating as many social taboos as possible in 90 minutes. Significantly grosser things have been made since 1972 — watching shock videos like “2 Girls 1 Cup” in the late aughts was arguably a more scarring rite of passage than Flamingos was for my parents’ generation — yet Waters’s trashterpiece remains notable partly because of what it spawned: Waters’s career trajectory from no-budget filmmaker into a legendary queer elder; Divine’s rise to stardom and influence on drag; the cult of midnight movies; as well as Jackass and other joyous celebrations in bad taste involving the misuse of excrement.

No doubt queer culture had softened around the edges in the intervening 50 years to make way for mainstream cultural assimilation and various personal sensitivities (though I’d argue John Waters is un-cancellable), which is why Flamingos retains the power to shock, offend, and turn stomachs in 2022. I’d even go as far as to bet that the same right-wing zealots rallying behind “Don’t Say Gay” bills and the criminalization of youth gender transition would take Flamingos at face value as a cinéma vérité exposé about degeneracy in the LGBTQ community. But upon latest rewatch, what’s far more provocative to me is the sheer audacity with which the film flouts its unapologetically filthy queerness. Divine power-walks through Baltimore’s scuzzy city streets as if she owns the place, head held high against gawking looks and hastily turned heads, proud to be “the filthiest person alive.” It’s a beautiful little moment in a movie that looks like it was unearthed at a crime scene. Pink Flamingos is more than a dirty movie where a drag queen eats actual dog shit — it’s pride in its most salient form.

Nicole Veneto graduated from Brandeis University with an MA in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, concentrating on feminist media studies. Her writing has been featured in MAI Feminism & Visual Culture, Film Matters Magazine, and Boston University’s Hoochie Reader. She’s the co-host of the new podcast Marvelous! Or, the Death of Cinema. You can follow her on Letterboxd and Twitter @kuntsuragi for weird and niche movie recommendations.

Silent Running

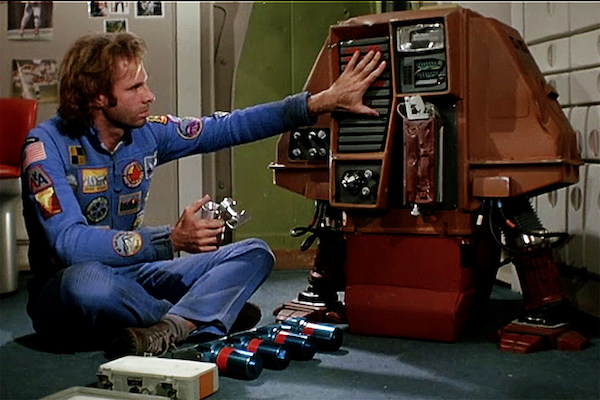

Bruce Dern and a robotic drone in 1972’s ecological dystopian film, Silent Running.

When Silent Running was released in the spring of 1972, we were still sending Americans to the Moon, Earth Day was 23 months old, and the US Army had ‘fessed up that 700 fraggings had been committed in Vietnam over the past two years. Director Douglas Trumbull, who died this past February, braided these three cultural forces into what endures as an iconic ecological dystopia. The premise: the very last American forests, along with other ecosystems, have been sealed in pressurized domes to be preserved in outer space. That is, until orders come to jettison and nuke the habitats and return the spacecraft to commercial use. Silent Running isn’t a science-fictional warning, but a manifestation of the “Future Shock” Alvin Toffler wrote about in his best-selling 1970 book of the same name. Silent Running is a response to, and a manifestation of, what stood in opposition to the optimism embodied by three Apollo missions. This included the rise of conservationism inspired by the Apollo Missions (and the report about climate change in 1972’s “The Limits of Growth”) and the moral rot of the Vietnam War.

Freeman Lowell, the long-haired protagonist of Silent Running, is brilliantly played by Bruce Dern. He has the same thousand-yard stare we used to see in front of VFW Clubs as they closed and methadone clinics as they opened. He incarnates these cultural forces: he’s an astronaut, a conservationist, and, by murdering his crewmates in order to save the domed forest on the spacecraft, he’s fragged guys in his “unit” rather than follow an immoral order to detonate the wilderness. There would be no Earth Day if not for the Apollo Missions: on December 24, 1968, 11 months after Tet, the famous “Earthrise” photo was snapped by astronaut Bill Anders. “‘[E]arthrise’ raised the level of ecoconsciousness that had been stirring even before Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring,” wrote Kathleen Rogers, president of the Earth Day Network. It was a picture that reflected American ingenuity and promise as well as the preciousness of life on Earth in the void of outer space. We actually see that picture in Silent Running — as an image that Lowell sights through a telescope set up in the forest dome.

Silent Running forces viewers to confront the moral choice Lowell faces: “Is it morally acceptable to kill three humans to preserve the last plant and animal life in the Solar System?”

After making the choice to save that last scrap of wildlife, Lowell hijacks the spacecraft and goes AWOL into that (albeit artificial) wilderness. His quasi-Walden escape mirrors the path taken by traumatized veterans since the end of WWII, when Farley Mowat helped found the “Back to the Land” movement (the darker aspects of which are explored in the 1977 Canadian survival film, Rituals). Scarred by Vietnam, many vets became hermits in the woods: see the documentary America Undercover: Soldiers in Hiding. Trumbull told Dern to think of Lowell as “a guy lost in the Sierras with his three dogs.” He’s atoning for his guilt, at times wearing a robe like St. Francis’s as he takes care of animals living in the dome. Maybe this is a riff on the zeitgeist that led Franco Zefferelli to make his St. Francis biopic Brother Sun, Sister Moon that same year, and that launched the “Mountain Men” films of the era, like Jeremiah Johnson and Man in the Wilderness.

Lowell’s companions on the spacecraft, the “three dogs,” are robotic drones he renames Huey, Dewey, and Louie. (Joel Hodgeson has acknowledged that Silent Running, a movie about a guy stranded in space with three robots, was the inspiration behind Mystery Science Theater 3000.) To create the drones’ distinctive waddle, Trumbull hired bilateral amputees who could walk on their hands for the roles. The director auditioned, among others, disabled Vietnam vets, some of whom worked in the film’s effects shop, building spaceship miniatures. But even in that artificial wilderness, with his robot “dogs” — the film implies the drones are newly sentient beings capable of suffering, so we are responsible for them, the way we are for wildlife — Lowell can’t outrun his shell shock. Wracked by guilt, he has flashbacks in the spacecraft’s cargo bay, where (tellingly) containers bearing the logos of major US corporations are stacked, most notably those of Dow Chemical. The suits at Dow believed that helping with the production of Silent Running would counter the negative PR it suffered from for manufacturing napalm. Yet by staging Lowell’s implosion with corporate logos in the background, Trumbull suggests that Vietnam threw our psychological ecosystems out of whack in the same way corporate monsters were, and are,

Lowell cannot live with what he has done and, at the end of the film, as a rescue mission approaches, commits suicide. Crying, he confesses to Dewey, “Things just haven’t worked out for me.” He has been trying to heal a wilderness, but he has failed to heal himself. That uniquely American, Transcendentalist ideal of finding salvation in Nature is beyond him. His inability to cope is ours — it is America’s tragedy. There is no balm for it, just as there wasn’t for Robert De Niro’s character, too wounded to find solace in Nature upon his return from Vietnam, in The Deer Hunter — written by Deric Washburn and Michael Cimino, who also wrote the first draft of Silent Running.

Lowell entrusts the forest to Dewey, a newly sentient, and above all else, innocent, being. Silent Running reflects the debilitation of emotional trauma, but the innocence of Dewey remains. Through that solitary little being some of our innocence is restored, though it is heartrendingly tenuous. In a final image — seared into the memories of those who respond deeply to this film — Dewey, adrift and alone in space, tends a sapling with a dented children’s watering can.

Novelist, essayist, and cultural critic Michael Marano has been writing professionally about film since 1990. When he was a little kid in 1974 and saw Silent Running for the first time on TV, he bawled his eyes out. Rewatching it for this article, he did so again.

Tagged: Bruce Dern, Douglas Trumbull, John Waters, Marjoe, Marjoe Gortner, Pink Flamingos