Television Review: Ken Burns’s “Benjamin Franklin” — Gauzy Soft-Core Patriotism

By Daniel Lazare

Corporate antiracism — Bank of America is a major sponsor for the documentary — causes Ken Burns to pull his punches.

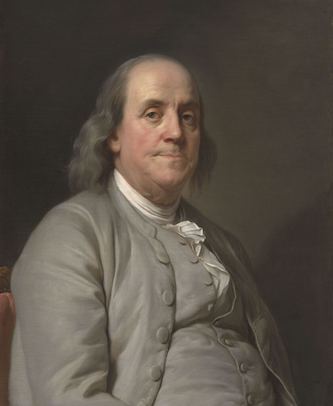

Benjamin Franklin, by Joseph Siffred Duplessis, c. 1785. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Benjamin Franklin, a four-hour documentary that premiered this Monday on PBS, is standard Ken Burns fare. This is no more a put-down than referring to a painting as standard Corot. All the usual Burnsian elements are there: the folksy Peter Coyote narration, the old-fashioned musical score, the interviews with academics, and, above all, the pacing. As surely everyone knows by now, Burns is a master at drawing the viewer in as the tale slowly unfolds. Of course, it doesn’t hurt when you have someone like Franklin as your subject, the archetypal self-made man whose life was one of the most interesting and dramatic of the 18th century.

Two other Ken Burns elements are also present: gauzy soft-core patriotism and a focus on race. Not that zeroing in on race is a bad thing. But what’s interesting is the way Burns sees the problem — as a blot on a country that’s otherwise stainless. The New Yorker once described Burns’s “default conversational setting” as “Commencement Address,” and when it comes to racism, it’s easy to imagine him exhorting fresh-faced graduates to go forth and conquer America’s sole remaining flaw so it can be even “more perfect” than it already is.

The documentary presents Franklin as “the embodiment of the American dream” due to his drive and ambition, and there’s no doubt that the man was a dynamo of self-improvement. After running away from a tyrannical older brother in Boston and arriving penniless at age 17 in Philadelphia, he found work as a printer, opened his own shop, and then built a publishing empire extending across the colonies. Reinventing himself as a world-class scientist in his mid-40s, he proved that lightning was no different than the sparks generated by rubbing a glass jar with a piece of cloth. Theologians wrung their hands because it meant that lightning was no longer the wrath of God. But Kant called him a modern Prometheus for stealing the fire of heaven.

As if that weren’t enough, Franklin then threw himself into a political career in which he tried to make peace between America and Great Britain, helped Thomas Jefferson draft the Declaration of Independence, lined up French support for the Revolutionary War, feuded with John Adams, took an active role in the 1787 Constitutional Convention, and took over as president of the country’s first major abolitionist organization, the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. Noting that the Constitution calls for “promoting the Welfare & Securing the blessings of liberty to the People,” he submitted a petition in 1790 reminding Congress “that these blessings ought rightfully to be administered without distinction of Colour.” But the House voted the petition down by a margin of 29-25, while the Senate tabled it without debate.

As the historian Bernard Bailyn remarks in one of Burns’s characteristically soft-lit interviews, slavery “was not a major public issue” prior to independence. “After the revolution,” he adds, “there never was a time when it wasn’t.” Franklin was the first person to set the irrepressible conflict in motion.

It’s no wonder that, when Franklin’s daughter Sally assured him on his deathbed in April 1790 that he would live “many more years,” he replied, “I hope not.” He had already crammed enough into his life for a dozen ordinary people and there was no room for more.

But Franklin had his dark side, as Burns also notes. Poor Richard’s Almanack, the publication that made him rich, ran ads for the sale of Black people and the return of runaways. At various points Franklin owned a half-dozen slaves of his own. He opposed the slave trade not on moral grounds, but because he believed that too many enslaved Blacks would make white settlers lazy and “enfeebled.” He argued for a whites-only immigration policy in which Spaniards, Italians, French, Russians, and even Swedes would be barred as overly “swarthy.” Franklin believed in America not only as an economic enterprise but as a racial project as well.

This warts-and-all portrait is unsparing, and for that we can be grateful. But elsewhere, corporate antiracism — Bank of America is a major sponsor — causes Burns to pull his punches. The documentary notes that the new revolutionary army included “free African-Americans and enslaved men hoping to be freed when the war ended.” But it doesn’t mention that such hopes were dashed when Southern slaveholders vetoed a proposal to grant slave soldiers their freedom in 1779. It lauds Franklin’s role in negotiating the Treaty of Paris ending the Revolutionary War in 1783 and especially for standing firm against British demands that America pay reparations for Tory losses. But it doesn’t mention that, at American insistence, the treaty included a plank stipulating that the retreating British were not to carry “away any Negroes or other property” and that Washington personally protested when Sir Guy Carleton, the British commander, refused to return ex-slaves who had run away to join the British side. The Americans would continue to demand reparations for their lost property well into the 1790s.

The historian Erica Dunbar, another of Burns’s academic talking heads, says that Franklin “sidestepped the issue of slavery” at the Constitutional Convention. This suggests that slavery was something he and other delegates tried to avoid when, in fact, they took active measures to shore it up. They did so in a multitude of ways: by approving the notorious three-fifths clause providing slaveholders with extra representation in the House; by granting each state equal representation in the Senate, which helped insure that slave states would have an unbreakable lock on that body until the Civil War; by using the same three-fifths clause to give slave-owners extra clout in the Electoral College; by requiring the new federal government to put down slave rebellions; by stipulating that the slave trade would continue untouched for another 20 years, and, finally, by crafting an amending clause that would be so favorable to the slave states that it would give them an effective veto over any and all constitutional change. Slavery was so impregnable as a result that it would take a second revolutionary war to dislodge it.

After helping to entrench slavery in 1787, Franklin thus called upon Congress to abolish it in 1790. Was this a last-ditch effort to make up for a record that was overwhelmingly negative? Or was it an empty gesture whose sole purpose was to put his reputation in the best possible light? It’s not the sort of problem that Burns is inclined to linger over. After knocking Franklin’s halo askew, he wants to make sure it is back in place in time for his hero to make his exit.

“There’s nothing dreamy or romantic about Franklin,” Stacey Schiff, author of a Franklin biography and a former New York Times columnist, says near the end of the film. “But in that self-improving, marvelously protean way, there’s something about him that so much becomes what we all quest for, what we think of as the sort of American ingenuity, the American feeling that we can accomplish anything.”

What such words mean is anybody’s guess. But after gridlock, a coup d’état, a growing gap between rich and poor, and a culture war that couldn’t be more poisonous, it is clear that, while some Americans are still individually ambitious, collectively they don’t have a clue as to how to put the country into anything resembling proper democratic order. Since Ben Franklin helped set this society in motion, perhaps Burns’s next movie will examine what he did wrong. If so, I doubt very much that Bank of America will want to fund it.

Daniel Lazare is the author of The Frozen Republic and other books about the US Constitution and US policy. He has written for a wide variety of publications including Harper’s and the London Review of Books. He currently writes regularly for the Weekly Worker, a socialist newspaper in London.

Tagged: American racism, Bank of Boston, Benjamin Franklin, Dan Lazare, Ken Burns

Perhaps Ken Burns should look for someone to fund a documentary about how major banks around the world (including Bank of America) are still financing fossil fuel companies to the tune of trillions of dollars. These banks are healthy, ultra-wealthy, and not-so-wisely helping to destroy the planet.

From a March 24th 2021 story on the CNBC online magazine, Make It:

I am trying to watch this but the background music is louder than the speakers. Kind of annoying. Another documentary of BF is dryer, perhaps, but gives a fuller accounting of what, where and when he did what he did. Usually I like Ken Burns work.

Au contraire, sir: https://www.history.com/news/the-ex-slaves-who-fought-with-the-british — thousands of Black Loyalists in fact emigrated to Canada and throughout the Caribbean as a result of Lord Dunmore’s declaration, so it certainly was a successful military strategy. I was raised on Harbour Island, Bahamas … in Dunmore Town, where he lived and worked after he left the USA. Within the continental USA, freed slaves like Biddy Mason and others created the First A.M.E. churches that continue to this day.

Bill,

international Banking is a too controversial topic for Ken Burns. It took him over 40 years to do a series on the very politically, financially and socially nuanced Viet Nam War. He regurgitated WWII ad nauseam before taking own this topic. At a WWII documentary screening, I saw audience members at the Coolidge Corner Theatre castigate him about not dealing with the Viet Nam era and War. Embarrassingly, he agreed that a film series needed to be made. There are too many taboos associated with international banking, perhaps some that may be treacherous and dangerous, for Burns and his PBS sponsored to get involved with.

Hi Mark:

I agree with you — but climate change, and how mega banks here and elsewhere are helping to destroy nature, is not a controversial issue. It is essential, it is about survival. These profit-crazed banks are influencing what Burns, NPR, and PBS cover, but we need these trusted outlets to fight free of their well-heeled supporters. So they must be publicly shamed. The banks are investing record amounts in fossil fuels while at the same time they are air brushing their brands, pumping money into sterilizing arts and culture. Seems to me that whenever we catch Bank of America or any other bank funding the arts, the hypocrisy of the money men who are killing the planet MUST BE CALLED OUT! I believe that arts critics will do that in the future — I am just ahead of the curve ….

Bill,

Amen.

Mark

Despite PBS and NPR being some of the best mainstream TV and radio around, I think that it works as Soma for the college educated. It keeps us becalmed. Burns is a wonderful filmmaker, but his penchant for seeing the rosy hopeful side of the American future is nearly pathological. He’s like a religious fanatic in that regard. According to Burns, racism and the political imperfections of America are on the way out! I saw some of the Franklin doc, but despite my interest in a genius who was able to conquer many fields (and was allowed to, because of his skin color, his ethnic background) I thought it was somewhat boring. The kneejerk patriotic parts were hard to tolerate.