Book Review: “Call Me Cassandra” — The Beauty of Fait Accompli

By Marina Manoukian

You know how the story is going to end, but it can only unfold if you take Cassandra’s hand and follow where she knows to go. Believe that she knows the way.

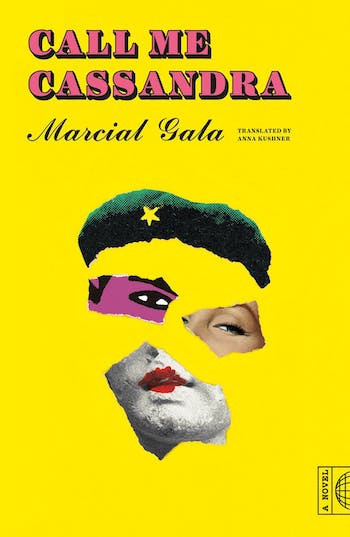

Call Me Cassandra by Marcial Gala. Translated by Anna Kushner. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 224 pages, $26.

The ability to predict the future may be described as experiencing time in a non-linear, non-three-dimensional way. To a two-dimensional being, experiencing the world in three-dimensions would be an absurdity. To three-dimensional beings, the idea of experiencing time though some sort of fourth-dimension would be just as ridiculous. So, at its core, clairvoyance means participating in time in an impossible way. And predictions of the future often sound ludicrous to three-dimensional ears.

A reader cannot help but read through a novel in a linear fashion, though there are many fictions that play with nonlinear narrative, such as Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch and Lyudmila Ulitskaya’s The Big Green Tent. But the distinctive beauty of Call Me Cassandra is that its nonlinear narrative echoes the narrator’s own fractured experience of time.

The protagonist of Marcial Gala’s novel is Rauli Iriarte, a Cuban from Cienfuegos who is the reincarnation of the Trojan princess Cassandra. From the beginning of the story, both Rauli and the reader know the fate that awaits, a fate not unlike the Greek prophetess’s own: “I will clench my teeth, I’ve learned that in successive lives, to clench my teeth and take it.” Cassandra’s curse is that she can predict the future, but no one will believe her. Frankly, that seems to be more of a curse on those around Cassandra than on the woman herself. No one is exempt from the future, so the question becomes— is it more tragic to know and not to be believed? Or to disbelieve until it’s too late?

Rauli’s fate is set from his first revelation as Cassandra, “to be here in Angola and die in the Old World where everything began, my Zeus, where I was first Cassandra such a long time ago.” To return to the Old World means to “resume my place in Hecuba’s womb and become again that woman most abhorred by the gods, I will again be Cassandra the mad, believed by no one, I will go back, yes, but now I’m in the schoolyard clutching my stomach because they’ve hit me again.” This may not even be Cassandra’s first return. At one point, Apollo tells Rauli/Cassandra that their fate is to “return to the Old World to die again, and that is your sentence, to repeat the cycle for eternity.” But the gods aren’t always known for their honesty.

The story opens beautifully with a description of a morning caught in its endless recurrence, and, although Rauli doesn’t hide his impending fate from the reader, his desire to find eternity in that morning can be felt throughout the novel.

“It’s very early, so everyone in the house is still sleeping, but I got up, opened the door, and came out to the balcony. I brought over a chair from the living room to get comfortable. I’m ten years old and it’s Sunday, so there’s no school, I can spend the morning watching the sea and the morning stretch out to infinity, but then I hear my mother’s voice behind me…I want to spend a long time watching the sea, until the sea runs out before my eyes and becomes nothing more than a white line that makes my eyes tear up.”

Sent off to fight in the battlefields of Angola as part of Operation Carlota, the Cuban involvement in the Angolan Civil War, the story is gradually revealed as time folds back onto itself. There’s no doubt about what’s to come, but the exact details are known only to Cassandra/Rauli and, via gentle bursts, and they’re slowly revealed to the reader. Scenes bleed back and forth into one another, collaging together pieces until the entirety of Gala’s stained glass window becomes clear.

This novel explores multiplicity and combinations, so it should not be surprising that there are few singularities in the text. Even the gods exist as multiples, Greek gods, Yoruba Orishas, and Egyptian deities walk in to guide Cassandra/Rauli back to the Old World. Rauli doubles with his Aunt Nancy, mirrors the young Katerina, drifts alongside his brother, and even plays Wendy to Captain Hook. There are no sharp divides, even between the book’s contrasting figures; lines of identity are so murky here that the best way to describe them would be amorphous. But, despite the liquidity of the selves in the novel, the solitude of the characters bleeds through.

While reading Call Me Cassandra in Anna Kushner’s superb translation, another significant aspect of the story demands attention. Just as Cassandra and Rauli inhabit one character, so the translator and the author inhabit the same text. And while it’s easy to try and draw lines between where one ends and the other begins, sensibilities aren’t so easily partitioned. Perhaps this desire to disconnect is where the trouble begins, just as we try to neatly disconnect past, present, and future. An,d although this multiplicity may not seem to apply when reading the text in the original Spanish, who’s to say that Cassandra’s reincarnation doesn’t also arise through language? With every translation comes another return.

Ultimately, the question remains: should the reader believe Cassandra? Disbelief inevitably limits your interpretation of the world. Gala, who also wrote the highly praised The Black Cathedral, which was also translated into English by Kushner, invites the reader in Call Me Cassandra to step into Cassandra/Rauli’s shoes, even if only for a moment. Because of this demand for empathy, the book takes on the cathartic power of traditional tragedies — the destruction Rauli experiences, witnessed by the reader, lingers in the mind and heart. You know how the story is going to end, but it can only unfold if you take Cassandra’s hand and follow where she knows to go. Believe that she knows the way.

Note: this novel contains occasional descriptions of sexual assault.

Marina Manoukian is a writer of the Armenian diaspora. A reader, writer, and collage artist, she currently resides in Berlin, Germany. Her writing has been published with Yes Poetry, Grunge, and Full Stop Review, among others. Find more of her work at marinamanoukian.com or on Twitter/Instagram at @crimeiscommon