December Short Fuses – Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Jazz

This is an Xmas album that isn’t just minimally bearable, it’s flat-out great.

Norah Jones released a Christmas album!

Norah Jones released a Christmas album!

OK, I just lost 75 percent of my readers. Half aren’t interested in Christmas music, and half of those remaining have an irrational allergy to Norah Jones. But those who are still with me are in for a real treat. I Dream of Christmas (Blue Note) is a Christmas album that isn’t just minimally bearable, it’s flat-out great.

Jones has a warm and honest voice, well suited for a Christmas album. She slinks and purrs her way through the Christmas romance songs like “Blue Christmas,” “What Are You Doing New Year’s Eve?,” and “A Holiday With You.” As if answering someone’s dare, she turns the Chipmunks’ “Christmas Don’t Be Late” into a slow-grinding bordello striptease. Somehow, the longer she stays in New York, the better and sexier her Texas accent gets.

To her credit, Jones writes or co-writes six of the 13 songs, so the album isn’t the same old set of tired holiday standards. The originals are all clever and melodic in the spirit of the genre, and it would be welcome to hear them covered by others (especially country bands). “It’s Only Christmas Once a Year” alludes to the miserable COVID Christmas many had last year, and it reminds us to enjoy the times we have because we never know what may come.

Finally, Norah, if you’re reading this, bless you for following Peggy Lee’s lead and getting rid of the all-time stupidest lyrics ever in “Winter Wonderland.” You know the ones I mean. She replaces them with the slightly sardonic “In the meadow we can build a snowman/And pretend that he’s a Santa clown/We’ll have lots of fun with Mr. Snowman/Until the other kiddies knock him down.”

Let the Bostonians have their snow and sleigh bells, but this one is for those enjoying the holidays on the front porch with mint juleps.

— Allen Michie

This release is a winner: a concert by two of America’s greatest singers at a splendid moment in their respective careers.

What did prominent musical organizations do during the first year and a half of the pandemic, when health considerations largely ruled out public performances and recording sessions? Well, some of the savvier ones dug into their vault of previous recorded performances and made them available, whether through streaming or on physical CDs or both. The Boston Modern Orchestra Project (and its affiliated Odyssey Opera), for example, as I have discussed on this site.

What did prominent musical organizations do during the first year and a half of the pandemic, when health considerations largely ruled out public performances and recording sessions? Well, some of the savvier ones dug into their vault of previous recorded performances and made them available, whether through streaming or on physical CDs or both. The Boston Modern Orchestra Project (and its affiliated Odyssey Opera), for example, as I have discussed on this site.

The New York Festival of Song is another such. NYFOS, led by its co-founder, pianist Steven Blier, took the opportunity to create a record company, NYFOS Records, and its first release is an amazing one: From Rags to Riches: 100 Years of American Song. Not that NYFOS haven’t been available before, but always on other labels (such as Bridge, Koch, and New World).

But this release is a winner and promises all kinds of exciting follow-ups. It consists of an entire concert (or perhaps most of one) that was given on March 23, 2000, at the Kaye Playhouse at Hunter College by two of America’s greatest singers at a splendid moment in their respective careers: mezzo-soprano Stephanie Blythe and tenor William Burden. They provide an overview of American songs — the CD moves chronologically — of quite varied kinds: a comic vaudeville number (“My Lady Frog” by Will Marion Cook); Broadway numbers (“Wrong Note Rag,” from Leonard Bernstein’s Wonderful Town; “The Ballad of [John Wilkes] Booth,” from Stephen Sondheim’s Assassins; and “Nickel Under the Foot,” from Marc Blitzstein’s The Cradle Will Rock); jazz and jazz-flavored tunes (“’Round Midnight,” by Thelonious Monk and “Hit the Road,” by Eubie Blake); and art songs (by, among others, Charles Tomlinson Griffes, Samuel Barber, and William Bolcom). My favorite cut: Jonathan Larson’s song “Hosing the Furniture,” which Blier (in his brief but pointed jacket-essay) calls “a hilarious feminist tract.”

Blythe and Burden negotiate with aplomb the challenges of singing with beautiful, rounded tone while also putting across a text, whether gently evocative or sassy. Blythe sings six numbers, Burden eight, and they do three numbers together. Throughout they are accompanied, cushioned, supported, and brilliantly partnered by pianist (and Festival co-founder) Blier, who also adapts in imaginative and flexible ways the piano parts for many of the popular-music and Broadway numbers. The Monk tune is atmospherically arranged by noted song and opera composer Ricky Ian Gordon.

The track listings are a little laconic: they could have mentioned which show each Broadway number comes from. For example, “Thousands of Miles” (Kurt Weill, words by Maxwell Anderson) is from the achingly affecting Lost in the Stars. But such info can be easily located online. Meanwhile, we can all be grateful for this amazing, belated release of what was clearly an alternatingly fun and touching night in a happily crowded theater.

— Ralph P. Locke

Classical Music

One gets a better sense here than on most discs of how ingenious Berlioz’s ear for sonic invention was.

Hector Berlioz’s Requiem is one of the idiosyncratic French composer’s most original works. It calls for immense forces and a huge performance area — spatial effects are written into numerous parts of the score, most notably during the “Dies irae” sequence. As such, it’s one of Berlioz’s most challenging pieces to present and successfully record.

Antonio Pappano’s new account of the piece (RCO Live) with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and the Chorus of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia is a remarkable achievement, then, just on a technical level.

Indeed, one gets a better sense here than on most discs of how ingenious Berlioz’s ear for sonic invention was. In the big moments, like the “Tuba mirum,” there’s a strong sense of directionality in the placement of the four brass choirs. Yet the chorus is always central to the action and never out of balance; neither is the orchestra swamped by the antiphonal groups (or vice versa). Bottom line: there’s some fine engineering on display.

Also, the quiet spots — like the instrumental detailing on the reprise of the “Sanctus,” with its soft cymbal crashes and string aureoles — shine.

The cumulative listening experience, then, exceeds the Requiem’s reputation as being merely a parade of spectacular effects. Rather, Pappano draws out the music’s beating heart and finds — despite Berlioz’s atheism — a genuine sense of devotion in these pages.

He does this primarily through a careful attention to the Requiem’s dynamic indications and textural balances. Accordingly, its bold contrasts — from the fury of the “Tuba mirum” to the spare desolation of the “Quid sum miser” or the “Hostias”‘ resonant exchanges between voices and flute/trombone quintet — speak characterfully and humanely.

True, there are a few episodes of scrappy choral intonation, but nothing outside the norm: this is a Berlioz Requiem that’s both gripping and touching.

For about half of this disc, the Russian singer, firmly in her prime at age 50, is magnificent.

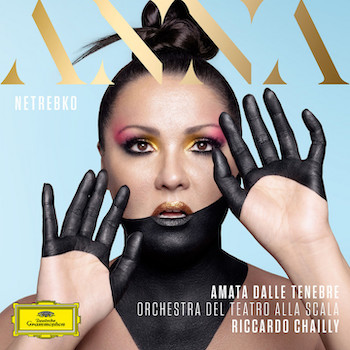

Amata dalle tenebre, soprano Anna Netrebko’s latest release (Deutsche Grammophon), straddles, if you will, the shadows and the sunlight.

Amata dalle tenebre, soprano Anna Netrebko’s latest release (Deutsche Grammophon), straddles, if you will, the shadows and the sunlight.

For about half of it, the Russian singer, firmly in her prime at age 50, is magnificent. Italian and Russian fare is clearly her calling card. “Poveri fiori,” from Adriana Lecouvreur, soars here, as does Aida’s “Ritorna vincitor.” Netrebko’s no less impressive in Elisabeth’s aria “Tu che le vanità” from Verdi’s Don Carlo.

A pair of Puccini arias — “Un bel di vedremo” (from Madama Butterfly) and “Sola, perduta, abbandonata” (from Manon Lescaut) — further showcase the astonishing gradations of intensity in Netrebko’s instrument, while Lisa’s Act 3 aria from Tchaikovsky’s Pique dame offers all the requisite sweep, pathos, and color one might desire.

Then there’s the rest of the disc, which consists of German and English-language arias.

Some of it, admittedly, simply doesn’t match in fervency. Netrebko’s “Einsam in trüben Tagen” (from Lohengrin), for instance, is nicely shaded and pitch-perfect yet doesn’t register emotionally. Nor does Ariadne auf Naxos’s “Es gibt ein Reich.”

At other times, the singing occasionally borders on the strident (“Dich teure Halle” from Tannhäuser) and the stiff (“Thy hand, Belinda” and “When I am laid” from Dido and Aeneas).

Perhaps most frustrating is Netrebko’s soulless take on the “Liebestod” from Tristan und Isolde. Again: the notes are all there, diction is excellent, and the line unfolds naturally. But none of this compensates for an interpretation that’s passionless, especially when the competition includes Margaret Price and Jessye Norman.

Taken together, it makes for a strikingly divergent release. Through it all, Riccardo Chailly and the Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala provide firm accompaniments, even though the ensemble is sometimes a bit too recessed in the mix.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Rock

This album makes me wonder what I am missing out on by not following contemporary indie rock more closely.

Had the eponymous debut by San Francisco’s The Umbrellas (Slumberland Records) been released when I was a kid or a teenager, the album would likely have long since become a personal favorite, perhaps even attaining classic status. Now, however, the agile mix of sweet and sour on this album has become somewhat familiar, but it still stands as one of my favorites of 2021. The self-described “4 piece janglers” triumph by flawlessly implementing said mix and having the chops to back up their adulation of those who perfected it

Had the eponymous debut by San Francisco’s The Umbrellas (Slumberland Records) been released when I was a kid or a teenager, the album would likely have long since become a personal favorite, perhaps even attaining classic status. Now, however, the agile mix of sweet and sour on this album has become somewhat familiar, but it still stands as one of my favorites of 2021. The self-described “4 piece janglers” triumph by flawlessly implementing said mix and having the chops to back up their adulation of those who perfected it

This delectable concoction comprises downbeat lyrics set to upbeat tempos, shared and swapped male/female vocals, ringing and chiming arpeggios, forceful strumming, full-relief bass lines, and assertive drumming. The result is an ideal ratio of delicacy and vigor.

The three singles that have been pulled so far should go a ways in convincing the curious and the skeptical. The perfectly twee pop titled “She Buys Herself Flowers,” “Near You,” and “Pictures” individually accentuate and collectively reinforce The Umbrellas’ many musical and lyrical virtues.

And the downpour of great songs doesn’t stop there. “Lonely,” “Happy,” “Galine,” “Never Available,” and “City Song” all could have been highlights on K or Sarah Records releases in the ’80s and ’90s. The slower-tempo numbers might not be quite as good, but they are essential to the album’s dynamic and the band’s aesthetic.

As for influences, “Lonely” ends with 25 seconds that sound cut and pasted from the 1986 Feelies album The Good Earth; the male vocals recall those of Beat Happening’s Calvin Johnson; and their fondness for Scottish groups like The Pastels and English ones such as The Field Mice is plain as day to the savvy listener and acknowledged by The Umbrellas.

This album — and the most recent one by Slumberland label mates and fellow San Franciscans The Reds, Pinks & Purples — makes me wonder what I am missing out on by not following contemporary indie rock more closely.

The Umbrellas will kick off a triple bill that includes Destroy Boys and Jigsaw Youth at Brighton Music Hall on Monday, December 6. (Doors at 6:30, show at 7:30; $15)

— Blake Maddux

Books

The Nature of Tomorrow correctly sees the climate crisis as a crisis of culture: we are far from being “woke” from our deep-seated belief that nature is inexhaustible.

In what ways can we imagine the environmental future, given that it will inevitably be shaped by the climate crisis? Michael Rawson’s usefully provocative survey The Nature of Tomorrow (Yale University Press, 233 pages) argues that our vision of the future should be informed by critiques of the popular stories and fantasies that have been told over the centuries about our stewardship of nature. “To reimagine the future one first needs to reimagine the past,” argues the historian, author of Eden on the Charles: The Making of Boston, a finalist for the 2011 Pulitzer Prize. This is a refreshing, if ironic, perspective, given that the climate emergency has so many peering forward for a solution rather than seeing the value of looking back — with skepticism.

In what ways can we imagine the environmental future, given that it will inevitably be shaped by the climate crisis? Michael Rawson’s usefully provocative survey The Nature of Tomorrow (Yale University Press, 233 pages) argues that our vision of the future should be informed by critiques of the popular stories and fantasies that have been told over the centuries about our stewardship of nature. “To reimagine the future one first needs to reimagine the past,” argues the historian, author of Eden on the Charles: The Making of Boston, a finalist for the 2011 Pulitzer Prize. This is a refreshing, if ironic, perspective, given that the climate emergency has so many peering forward for a solution rather than seeing the value of looking back — with skepticism.

There has been lots of scientific speculation about the steps (many extreme) that should be taken to mitigate looming disaster. There has been considerably less talk about the enormous political changes sure to come, for instance, when major cities around the globe find themselves (and their millions of inhabitants) under water. But there has been even less discussion about exploring the ways the West has dreamed over the centuries about what could (or can) be done to nature. It turns out that an assumption of perpetual abundance drove most of these Promethean visions, from Frances Bacon’s New Atlantis and the science fiction of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells to the futuristic ruminations of NASA, Disney, and the RAND Corporation. Whether utopian or dystopian, these visions shared the same elemental supposition — of limitless growth. Rawson believes that flipping this script will be a daunting task: we need to “change the dream of the modern world, at the heart of which is the paradoxical expectation of unlimited expansion on a finite planet.” Or, as Ursula Le Guin memorably summed up our tragic predicament: “The utopian imagination is trapped, like capitalism and industrialism and the human population, in a one-way future consisting only of growth.”

The Nature of Tomorrow excavates the past as a form of prescriptive education. The lesson is clear: our sense of infinite possibility has been yoked to an absurd faith that nature — by addled hook or agile crook — would surely provide whatever was necessary to make our delusions come true. The various schemes proposed throughout history to maintain our illusions of plenty are alarming, although there is some head-scratching amusement: in the 19th century, Joseph Fourier presciently foresaw the coming of “a warming world climate, melting polar region, and acidifying oceans,” but he and others saw the transformation as an opportunity for increasing nature’s productivity; H.G. Wells speculated that we would stop eating food and take baths in nutrients, and a pair of postwar American scientists popularized the notion that “sea water … resembles that wonderful table in Grimms’s fairy tale which is always covered with food at its master’s command. We only have to find out how to take the food from the table.” The myth of unflagging fertility underlines these past futuristic visions: the notion is that nature will always give us what we want, if we bring enough gung-ho ingenuity to the asking.

On the debit side, The Nature of Tomorrow‘s bullying maps of the future flash by at a quicksilver clip, which means that many entries just get a paragraph or two of context and analysis. Sometimes you wish Rawson would stop and focus, particularly with the arrival of 1972’s momentarily brake-applying Limits to Growth report, as well as the eco-utopias of that period and beyond. (I read Aldous Huxley’s Island in the late ’60s, when it was fodder for the counterculture. I must give his final novel another look when it turns 60 next year.) The historian is understandably concerned with how dangerously our fantasies of entitlement have recovered from that relative period of sanity. He correctly sees that we are experiencing a crisis of culture: the world is far from being “woke” from its deep-seated belief that nature is inexhaustible. “By the first decades of the twenty-first century, it was no easier to imagine a future without endless growth than it had been in the ’70s. In fact, it had become a lot harder.” Rawson makes his case that imaginatively revising the past will be essential in the difficult task of coming up with healthy new dreams of the future, “radical” visions of collective restraint and balance.

— Bill Marx

Tagged: Allen Michie, Anna Netrebko, Antonio Pappano, Bill-Marx, Blake Maddux, Chorus of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, From Rags to Riches: 100 Years of American Song, I Dream of Christmas, Jonathan Blumhofer, Michael Rawson, NYFOS Records, Norah Jones, Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala, Riccardo Chailly, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Slumberland Records, Steven Blier, The Nature of Tomorrow, The New York Festival of Song, The Umbrellas