Film Review: “Karen Dalton: In My Own Time” – (One-of-a-kind musical find)

By Ed Symkus

Singular folksinger Karen Dalton never made it to the big time. A new documentary suggests why.

Karen Dalton: In My Own Time, is available on VOD beginning Nov. 19.

I never met or caught a concert by folksinger Karen Dalton (1937-1993) — the 12-string guitarist with the raspy, intoxicating voice who put her own stamp on songs by other composers. But I vividly remember my first brush with her. In late 1971, I was working at the record store New England Music City. Someone put a promo copy of the new Karen Dalton album In My Own Time on the turntable, starting, for some reason, with the last track, “Are You Leaving for the Country.” That strange but alluring voice caressed me, embraced me, came close to making me swoon.

There’s a moment in the documentary Karen Dalton: In My Own Time when Australian singer-songwriter-balladeer-rocker Nick Cave talks about his first time hearing that album’s forlorn opener, a cover of Dino Valenti’s “Something on Your Mind.” He says that it made him cry, “not because it was sad, but because it was perfect.” He was referring to Dalton’s interpretation of it.

Odds are that you’ve never heard of Karen Dalton. She only made two albums, she preferred playing in friends’ living rooms over concert halls, and she was a troubled soul who was constantly dealing with personal demons, drug abuse, and emotional fragility, and just didn’t have much luck on her side.

This film, by first-time feature documentarians Richard Peete and Robert Yapkowitz, opens with that distinctive voice, a close-up of her seemingly forlorn face, and a performance of the sad, dreamy “Blues Jumped the Rabbit.”

Though there isn’t much live footage of Dalton extant, Peete and Yapkowitz sensibly pepper the film with audio segments of her singing pieces of Woody Guthrie’s “Pastures of Plenty,” Tim Hardin’s “Reason to Believe,” the traditional “Green Rocky Road,” and “Are You Leaving for the Country,” by her third husband, the singer-songwriter Richard Tucker. I was once again knocked for a loop when part way through that song the film cuts to a live, on-camera version of her singing it with a band.

The music is nicely complemented by selections from Dalton’s soul-baring journals and poetry, read off-camera by singer-songwriter Angel Olsen, as the words scrawl across the screen. Among the words: “My heart is a jackhammer, drilling, tearing up the pavement, the pavement of people’s lives.”

Of course, there’s also the obligatory biographical sketch: Grew up in Oklahoma during WWII, learned to play multiple instruments, left home and got married at 15. Had a child, but the marriage went south. Married again at 17. Another child, and an end to that marriage when, after falling in with a musical crowd, she split — alone — for New York, hoping to join the burgeoning folk music scene. As one of the film’s talking heads points out, “She gave up her role as a parent to be an artist.”

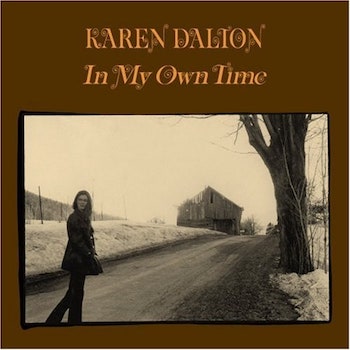

Vocalist Karen Dalton — “A strange but alluring voice caressed me, embraced me, came close to making me swoon.”

She did, however, return to Oklahoma to “kidnap” her daughter Abbie, and bring her back to New York with her. That, and many other stories, are told by Abbie and by various musicians, including friend Peter Stampfel, former boyfriend Hunt Middleton, and husband number three, Richard Tucker. One says she was sullen, another that she wasn’t very comfortable performing, another that she had anger issues with hecklers and with sound system problems.

One of the film’s strengths is that in many of the scenes in which people remember her, they do it with smiles, though some of the smiles are sad, and there are times when the storytellers get a little teary. An even more revealing component is the repeated sentences, “That was the last time I ever saw her” and “I never spoke with her again.”

Difficult as it is to choose a favorite highlight, I will settle for two: Dalton sitting on a stoop outside of her Colorado cabin, singing Fred Neil’s “Little Bit of Rain,” and any of the bits of her being interviewed on a 1976 broadcast of Bob Fass’s Radio Unnameable.

There’s a devastatingly heartbreaking postscript to the film. You won’t come out of it smiling. But hopefully you’ll have developed an interest in checking out her music.

Ed Symkus has been reviewing films and writing about the arts since 1975. A Boston native and Emerson College graduate, he co-wrote the book Wrestle Radio, USA: Grapplers Speak, went to Woodstock, collects novels by Harry Crews, Sax Rohmer, and John Wyndham, and has visited the Outer Hebrides, the Lofoten Islands, Anglesey, Mykonos, the Azores, Catalina, Kangaroo Island, and the Isle of Capri with his wife Lisa.

His favorite movie is And Now My Love. His least favorite is Liquid Sky, which he is convinced gave him the flu. He can be seen for five seconds in The Witches of Eastwick, staring right at the camera, just like the assistant director told him not to do.

Tagged: Ed Symkus, Karen Dalton, Karen Dalton: In My Own Time, Richard Peete

The night before graduation from Brandeis University in 1963 I spent the night in a cottage at Crane’s Beach with Karen Dalton and Richard Tucker. We were on acid and just the three of us. They played until dawn. It is an experience I vividly remember as they were remarkable musicians and singers. I was still tripping when I paused on stage, halted the ceremony, and slowly took giant steps to accept a diploma from a stunned Abe Sachar.

Ed,

Karen did not split alone to come to New York. She left with me, her sister Joy and a friend of mine named Art Benjamin. Art and her sister went to Philadelphia, and she and I went to my New York apartment on West 106th Street. Your story is a better story, but it isn’t true. We were all squeezed into my Renault 4CV.

Hi, Dick — Thanks for the correction. I re-watched part of the documentary to find out exactly what was said about that incident. At around the 43-minute mark, her daughter says, “She decided she was gonna go back to New York, try the other side. So I got in the car, she dropped me off in Oklahoma, and went on to New York.” No mention was made of anyone else in the car. She made it sound like Karen went on alone, so I assumed she did. Sorry about that — Ed