Visual Arts Review: The Photographs of Deana Lawson — Portals to Possibilities

By Chloe Pingeon

Viewers are invited to make what they will of the show’s images — to let their imaginations come up with their own expansive and beautiful stories.

Deana Lawson, Hair Advertisement, 2005. Pigment print. Courtesy the artist; Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York; and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles. © Deana Lawson

The galleries of the Deana Lawson exhibition (through February 22, 2022, at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art), are lined with wall-to-wall red carpeting. The space is warm. Hushed. A contrast to the traditional white cubes where visitors are invited to experience art. Here, you are in a new space entirely. A space in which the outside world is muted, pushed aside, at least a bit. Here, it is just Lawson and the public. That’s the way she likes it.

Lawson was born in Rochester, NY. Her mother worked for Kodak and her aunt was one of the first Black female ophthalmologists. It is understandable that her connection to visual art is multilayered; her work exhibited at the ICA intertwines photography, image, and heritage. She often focuses on the family photo, emphasizing images of intimacy — bodies in embrace or people relaxed in their homes. It is not always clear if this closeness should be taken as a personal drama or is about making a general observation about Black experience. Our interest in background information is not the point — perhaps even beside the point. Viewers are invited to make what they will of the show’s images — to let their imaginations come up with their own expansive and beautiful stories.

Five photographs hang in the first room of the exhibition. My eyes were immediately drawn to a pigmented black image of a red explosion. Tucked into the frame — so as to overlay the visual — is a small photograph of a woman. The piece is called Dana and Sirius B. The explosion is brilliant and powerful: almost symmetrical, but there’s enough imperfection so that it appears natural. It’s a star, Sirius B, and it would be invisible to the naked eye, overshadowed by its neighbor, Sirius A. In Lawson’s photograph, Sirius B is radiant. The woman in the overlaying photograph is young and smiling; it is Dana, Lawson’s twin sister. This is one of the only times in the show that Lawson identifies a subject in her photo. The frame of the piece is mirrored so that if you look at it from just the right angle, you see yourself looking back.

Across the room hangs Girls with Oiled Faces, an image of young Black twins in matching dresses sitting on a couch and looking at the camera, their expressions dull. There is no context given for this photograph. Perhaps this piece is a reflection of Lawson’s childhood as a twin. Perhaps not. At the entryway of this same gallery hangs Hair Advertisement. In this photo, a beautiful young woman stares coyly at the camera. It’s a photo of a photo: a picture of an advertisement that Lawson saw outside a hair salon in Rochester. At the ICA, she recycles the image, no doubt to satirize white society’s standards of beauty for Black women.

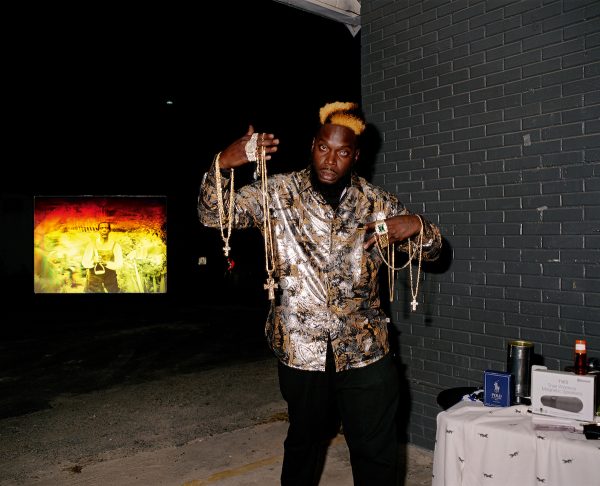

Deana Lawson, Black Gold (“Earth turns to gold, in the hands of the wise,” Rumi), 2021. Pigment print with embedded hologram. Courtesy the artist; Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York; and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles. © Deana Lawson

The exhibition is composed of eight rooms and the photographs are mostly portraiture, organized chronologically to document 20 years of Lawson’s increasing confidence. The pictures grow larger in size and become more self-aware over time. The second room features seven curated images. In the corner sits an assemblage of drugstore photographs. These kinds of arrangements reappear often throughout the exhibition, intentionally placed within the gallery’s more marginalized spaces. Each image tells its own story so that, together, the collage-like network is so complex that it is impossible to make sense of it all. It is an act of reclaiming the complications of Black identity, with an eye on the pervasive (and oppressive?) power of media and photography.

The same challenge is raised when Lawson’s photographs get bigger. They become overwhelming, the obvious attention to detail in their subjects’ postures and expressions juxtaposed with a shallow depth of field. The result is a paradox; viewers are given too much and too little information. When there are windows or doors in Lawson’s photographs, they are concealed with drapes or curtains. The effect is to suggest that, for this moment, the outside world is being excluded. In the corners of some of the galleries there are sometimes crystals, placed to strategically frame the photographs. These stones are art works in their own right, but they also transform the space into a frame that includes viewers.

The heart of the exhibition lies in the fifth room. Here, on one wall, hangs a series of photographs that Lawson did not take. The piece is called Mohawk Correctional Facility: Jazmin & Family. It’s composed of a collection of family portraits that show a man, a woman, and a child in varying poses. They are always standing against a cement wall painted blue and yellow. There is a painted plant on the lower corner of the wall, perhaps to suggest the outside world, albeit through primary colors and elementary strokes that feel far from natural. These are photographs of Lawson’s cousin Jazmin and her partner Erik; they were taken in the visiting center of the prison where Erik was incarcerated. The compilation is dedicated to the real: real years, a real family, and real space inside the prison. Across the gallery hangs the ironic The Garden. Here a naked couple is photographed surrounded by greenery. The presence of nature makes a sardonic comment on the pictures of prison confinement. Here Lawson juxtaposes freedom with captivity, American myth and reality.

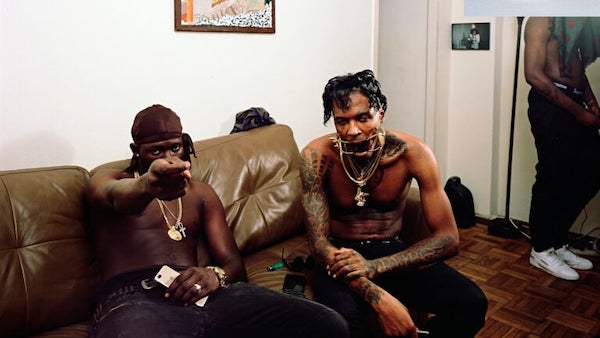

Deana Lawson, Nation, 2018. Pigment print and collaged photograph. Courtesy the artist; Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York; and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles. © Deana Lawson

In the final rooms of the exhibition, the silence of the earlier galleries is replaced by the sound of music. Ghanaian and Togolese women are heard singing an a cappella choral arrangement via audio from a 12-minute video loop in the exhibition’s final room. The singing becomes louder as you move through the galleries and note that the photographs on display are increasing in size. Also, the facial expressions and humanity of Lawson’s subjects become more profoundly moving as you progress. In the sixth room, where the audio is present but remains distant, a particular image demanded my attention. It’s titled Portal, and it’s another photograph without people. It is a close-up of part of a beat-up couch that’s covered in brown leather. There’s a gaping tear in the fabric. The allusion to poverty is clear, but so is Lawson’s demand that, by paying attention, we envision possibilities for transformation in that jaggedly empty space.

Chloe Pingeon is a rising senior at Boston College studying film and journalism. She has written regularly for the features and arts section of Boston College’s Independent Student Newspaper The Heights, and has also written for the culture section of Lithium Magazine. She is currently a creative development intern at Foundation Films.