Book Review: “The Wrong End of the Telescope” — A Stunning Achievement

By Roberta Silman

This is a wonderful novel about a pressing humanitarian subject, Syrian refugees and the people who helped them, as well as an exploration of identity and loss and triumph.

The Wrong End of the Telescope by Rabih Alameddine. Grove Press, 354 pages, $27

Really good prose is rare, and good prose combined with a compelling story is mesmerizing. I concluded that Rabih Alameddine was one of the finest contemporary writers in English when I reviewed An Unnecessary Woman, which I admired, and also when I reviewed The Angel of History, which I found disappointing. But now, in his seventh novel, The Wrong End of the Telescope, Alameddine has fulfilled his promise and hit his stride.

Really good prose is rare, and good prose combined with a compelling story is mesmerizing. I concluded that Rabih Alameddine was one of the finest contemporary writers in English when I reviewed An Unnecessary Woman, which I admired, and also when I reviewed The Angel of History, which I found disappointing. But now, in his seventh novel, The Wrong End of the Telescope, Alameddine has fulfilled his promise and hit his stride.

This is a wonderful book about a pressing humanitarian subject — Syrian refugees and the people who helped them in the camp called Moria on the island of Lesbos. And this is also a novel about identity and loss and triumph, whose protagonist is a transgender Arab American doctor named Mina Simpson, one of the most engaging characters in recent American fiction. So this becomes a book that is also about what it means to grow up in a society that will never accept you if you do not conform to their strict sexual mores, and about how you can escape. And thrive. And live to write about it.

How has Alameddine managed to write such an accessible book about such profound subjects? The clue may, possibly, be that he identifies as a visual artist, as well as a writer. Which makes sense, because this latest novel is written in much the same way Cézanne described painting a picture: one stroke after another, until you have an intimate and memorable portrait of what it is like to be thrust into the chaos of a refugee island, and also how you became who you are.

The strokes are short chapters with beguiling headings –“Round and Round We Go,” “You Made Me Do It,” “How I Learned to Drive,” for starters — in which we learn about Mina, who has lived with her partner Francine for 30 years in the United States. She has a week’s vacation and has come to the Middle East alone at the request of a friend working for an NGO that needs help. Mina is also taking this opportunity to reunite with her beloved brother Mazen, the only member of her original family in Lebanon with whom she is in touch. However, interspersed with those chapters is a running conversation, really a series of letters, from Mina to someone that sounds like Alameddine, himself. It is this conceit that I found so fascinating: we have not only a novel about Mina Simpson, but also — possibly — an autobiographical novel about Alameddine. Who was born in Amman, Jordan, 62 years ago of Lebanese Druze parents. Who emigrated first to England, then came to the United States for university and has degrees in both engineering and business. Who is gay and wrote his first novel about the AIDS crisis.

So here is a series of parallel stories and memories tied to each other by the affection and exasperation these two friends have for each other. The fact that one may be real and one a figment of the author’s imagination is an intriguing way for this enormously talented writer to tell his story, or the story of someone who sounds a lot like him. Here are excerpts from the first “letter” that give us the flavor of Mina’s voice in this book — the daring, the leaps, and the humor:

I should write this thing, you told me. You called it a thing, flicking your hand with a dismissive Levantine gesture. Every idiot thinks they’re a writer; they’re not…. You insisted I write the refugee story, as well as your story and mine. This thing … Memory is a wound, you said. And some things are released only by the act of writing. Unless I go in with my scalpel and suction to excavate, to clean, to bring into light, that wound festers, and the gangrene of decay will eat me alive.

And whatever you do, you said, don’t fucking call it A Lebanese Lesbian in Lesbos, just don’t.

I’m writing now. I’ll tell your story and mine.

I’ll write your story for you.

I plunge.

There are lots of characters who hover around Mina and the “you” she is addressing. At times, this novel feels like a trip to the theater — scenes of people coming and going, stepping up in emergencies, trying to meet and sometimes succeeding and sometimes failing, then relaxing into their memories and their pasts. There is also a wealth of detail about Lesbos and Moria and the airport and the roads and hotels and restaurants and clinics and tents and beggars and the homeless. The reader is spared nothing. The trajectory of the book is Mina’s friendship with a Syrian refugee named Sumaiya, who is dying of terminal liver cancer, and the efforts of Mina and her friend Emma to get Sumaiya and her family to a place where they feel safe and Sumaiya can say a civilized and meaningful goodbye to her husband and children. No small task, given the obstacles, and here is where we get a visceral picture of what these refugees, whom the world was so concerned about a few years ago and whom we hardly hear about anymore, went through. But this is also a novel in which people do and say unpredictable things, as when Sumaiya’s daughter asks Mina, “Are you a man?”

What ensues is a hilarious exchange between the embarrassed parents and Mina and Emma, with Emma saying,

“What are you going to tell her? This should be amusing.” I could see her eyes light up, an impish grin on her face. “I keep telling you to use lipstick, but you don’t listen to me. No, you never do. And those pants are horrific. The things I could do for you if you let me.”

But after Mina confesses, “I was born male, but that wasn’t who I was,” the Syrian family tells a story about a doctor in their little village who was the first to diagnose Sumaiya and who went from being a man to a woman in order to treat the people who needed care. “No one in the community betrayed him, of course. He was one of them. And so was she.”

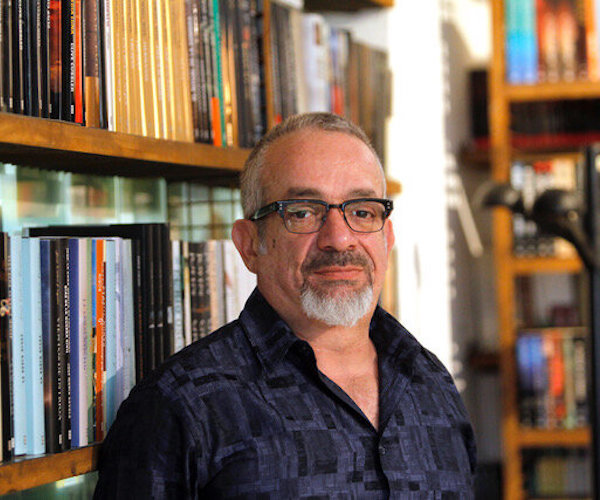

Author Rabih Alameddine — one of the finest contemporary writers in English. Photo: Grove Atlantic

At that point — about midway through the novel — everything opens up. We learn more about Mina’s enigmatic friend and how he realized he was gay and came out. Then, through a bizarre but believable story of an encounter in the jungle with a female orangutan, how Mina found the courage to recognize her true sexual identity. How she and her partner of three years, a woman named Jennifer, knew they were over. “In that eternity, under a gunmetal sky, as we looked at each other, a reversal. Ayman seeped down to the ground and Mina sprang to life.” This longest chapter of the book — entitled “The Women: Mrs Peel and Jennifer” — is its lynchpin. After we are taken into Mina’s confidence the book grows stronger, just as a friendship does when it deepens into a place where there are no holds barred, no more secrets. And toward the end we learn even more about Mina’s friend, his fears and panic and inability to cope among those he had come to help.

This novel is a stunning achievement. It is filled with amazing characters and insights and political opinions and history about the Middle East, as well as family stories, some of them brutal. Like all really good fiction, it has a sense of urgency, as well as intimacy. This story must be told, it is “necessary,” in Rilke’s terms, and if “you,” the writer, are not able to tell it, I will, declares Mina. But of course “you” has told it; he is the one who has not only written this beautiful work, he has also created Mina. So, The Wrong End of the Telescope is also about the very act of writing, what one can or can’t do, and how hard it is to tell a complicated story like this. But whether or not “you” is Alameddine or another fictional character, he has succeeded, brilliantly. By bringing to bear all he knows about the Middle East, he has broken new ground, infusing a narrative that details the savagery of contemporary life with grace and humor and compassion. For all its sadness, it is a story that leaves us with an indelible feeling of hope.

Roberta Silman is the author of four novels, a short story collection and two children’s books. Her latest novel, Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review), is in its second printing and is available on Amazon and at Campden Hill Books. It was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus and it is now available as an audio book from Alison Larkin Presents. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for the New York Times and Boston Globe, and writes regularly for the Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Roberta, you are amazing. I don’t envy you. I applaud you.

Xxx