Film Review: “Terra Femme” — Only Connect…

By Ezra Haber Glenn

Collectively, Terra Femme’s footage provides a window — or really, a suite of windows — that allows us to view a bygone world through the eyes of silent female gazers.

Terra Femme, directed by Courtney Stephens, will be available to watch via the Brattle Theatre’s “Brattlite” virtual screening room from November 5 through 11. Be sure to check out the Arts Fuse review of a film Stephens co-directed, The American Sector, “an amusing, quirky, and meditative road-trip/scavenger hunt.”

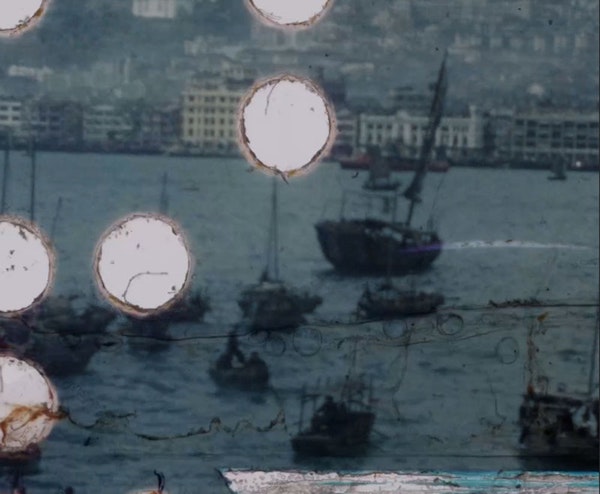

A visual from Terra Femme

Director Courtney Stephens’s latest work, Terra Femme, is more a journey than a film. It’s an evolving research project: assembling, viewing, cataloging, critiquing, and connecting with thousands of hours of archival footage from home-movies and amateur travelogues shot by women in the first half of the previous century. Stephens has stitched the silent footage into a one-hour tour, which she presents, often — as at the Brattle on Monday night — with live voice-over narration. (Or perhaps the pieces have been woven together — but by all means let’s not say “assembled,” with its mechanistic overtones. The appropriate metaphor would involve the more shifting, flexible fabric arts. What we have here is somewhere between a complex and beautiful tapestry and a fascinating and diverse patchwork crazy-quilt.)

The component films — their locations, subjects, circumstances, and technical qualities — are as varied as their authors, including home movies of family vacations, holidays, and even just trips down the block, never intended for public viewing; amateur works shown in once-common local film clubs; and a few examples of more “notable” women filmmakers and travelers, including the wives of British diplomats in the colonies, and the exploits of Aloha Wanderwell, an intrepid and charismatic young traveler sponsored by the Ford Motor Company to race around the world.

Whether live or recorded, the performance is surprisingly honest and human, powerfully effective without unnecessary affectation. The images and narration combine — at once both thoughtful and deeply-personal — as Stephens explores the intersections of gender, individuality, history, race, colonialism, the relationship between humans and nature, and the various meanings we discover and create as we move through, view, shape, and document different places and cultures.

A visual from Terra Femme.

In terms of film stock, Stephens was understandably limited by what has been preserved, archived, and made available. (This process of evaluation and loss emerges as a minor theme.) Still, she approaches this work with the eye of a magpie and the nose of a private detective. At each turn, she seem eager to lean in to extract whatever meaning she can from these sources, while being mindful of the limitations of the method. Her reflections and questions suggest an awareness of the danger of the disconnected Benjamin-style “Collector,” for whom “what is decisive in collecting is that the object is detached from all its original functions.”

It’s becoming commonplace these days to speak of each new nonfiction film pushing the edges of what the documentary can do — so much so that one might wonder whether this old form has any shape at all any more. To its credit, Terra Femme demonstrates the exciting potential of this emerging movement without any of the pretension of more experimental works, and without losing the intent of nonfiction, and archival/historical, film. Nothing is fabricated, the filmmaker’s interest is present but not so dominant as to crowd out the actual subject. As viewers we are invited in, not ignored, confused, or preached to.

Collectively, the footage provides a window — or really, a suite of windows, a multifaceted fenestration — allowing us to view the bygone world through the eyes of these silent female gazers. In passing, the film ponders to what extent this perspective is unique and gendered — “a lens of our own,” so to speak. But, for the most part, Stephens sets this meta-concern aside; she is more interested in just understanding these filmmakers as individuals in time and place. Rather than putting them on a new kind of pedestal — as representatives of a heretofore unrepresented group of auteurs waiting patiently to be lifted up and celebrated — she invites us, with her, to think about them, simply, as people who lived and traveled and saw and thought about things. Connection — with the past, with these people, with oneself — is the goal, even if that means not finding what one hopes or expects, and being willing to recognize and be satisfied with a sense of shared humanity. Isn’t that enough?

Ezra Haber Glenn is a Lecturer in MIT’s Department of Urban Studies & Planning, where he teaches a special subject on “The City in Film.” His essays, criticism, and reviews have been published in The Arts Fuse, CityLab, the Journal of the American Planning Association, Bright Lights Film Journal, WBUR’s The ARTery, Experience Magazine, the New York Observer, and Next City. He is the regular film reviewer for Planning magazine, and member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. Follow him on https://www.urbanfilm.org and https://twitter.com/UrbanFilmOrg.