Film Review: “Becoming Cousteau” – (To live on the land we must learn from the sea)

By Ed Symkus

Jacques Cousteau’s journey, from wannabe pilot to protector of the seas, is chronicled in a new documentary.

Becoming Cousteau, directed by Liz Garbus. Screening at Boston Common 19, AMC South Bay Center, Assembly Row 12, Framingham 15, and Braintree 10.

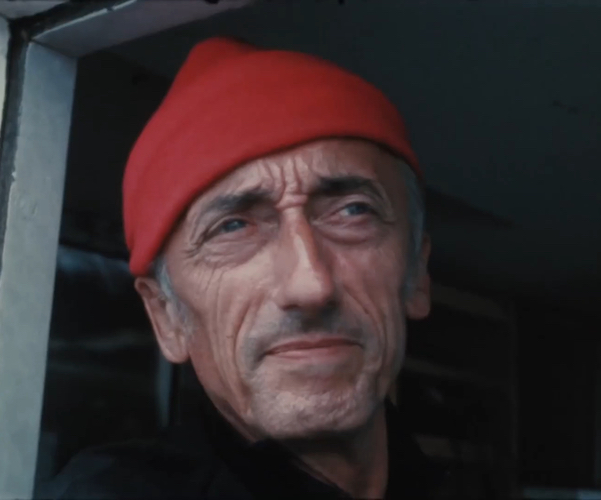

A scene from the documentary Becoming Cousteau.

There were many sides to Commander Jacques-Yves Cousteau (1910-1997). He was a man with a winning personality who achieved pop culture status well before the term existed — an ever-smiling, always inquisitive, extremely knowledgeable sailor and adventurer who made feature films and TV shows through which he shared his passion for life in the oceans. He was also an inventor who, partnering with the engineer Emile Gagnan, developed a regulator that led to the aqualung — a.k.a. self-contained underwater breathing apparatus (SCUBA) — which freed divers from using long air hoses. He won three Oscars (The Silent World, The Golden Fish, World without Sun), the Palme d’Or at Cannes (The Silent World), and a Jules Verne Lifetime Achievement Award. In his later years, he segued from being a restless explorer to becoming a champion of saving the environment. Oh, and he played the accordion.

All of that, and much more — including bouts of self-doubt and tragedy, and the revelation that Cousteau had a secret “second family”– is presented in Becoming Cousteau, the newest documentary from Liz Garbus (What Happened, Miss Simone?).

Garbus liberally sprinkles the film with interviews and voice-overs — some in French, some in English — with different people who knew, worked with, or lived with Cousteau over the years. But most of the words here are from Cousteau, via on-camera interviews or in voice-overs. One of Garbus’s nicest touches is to feature the voice of actor Vincent Cassel reading from Cousteau’s writings. The visuals serve as perfect complements to the biographical narrative: they include early “home” movies of Cousteau and friends, the filmmaker with his wife and ocean adventure partner Simone and their children Philippe and Jean-Michel, and still-astounding clips from Cousteau’s films and TV shows.

Garbus veers away from a strictly chronological format, and on a couple of occasions pops in an event that’s not only out of order in time, but also a bit jarring (like that business of the second family, consisting of his much younger mistress, Francine Triplet, and their two children).

Still, it’s easy to follow the trajectory of Cousteau’s life and career: An interest in movies as a young boy; being knocked out by underwater footage he saw when he was 12 (Garbus hints that it might have been the 1916 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea); joining the Naval Academy at 20, with plans of being a pilot; a terrible car accident that scotched that idea; his body’s recovery through swimming, spear fishing, and diving; an urge to find a way to be able to dive deeper; marriage to Simone; his purchase of an American-built minesweeper, which became his legendary boat the Calypso; a move into filmmaking (with his then-young intern Louis Malle); a shift into television, so he could reach a larger audience (The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau); his research work for oil companies in the early ’50s that gained him funds for his own projects (and thank goodness there’s no cancel culture absurdity here); his progression to the role of ardent environmentalist and protector of the seas.

Sure, the visuals are what’s going to make this film most memorable for most viewers, but there are also real gems among the spoken words.

Asked by a TV interviewer what extra insight he got about the sea by diving that he couldn’t get in museums, Cousteau smiles and says, “Have you ever experienced the difference between reading a book and doing it yourself? If you read a book about lovemaking, it’s not the same.”

In a voice-over, Malle explains, “Commander Cousteau is many things — a sailor, a scientist, an inventor. But it must be said, very clearly, he is a filmmaker.”

Casell, reading from Cousteau’s writings, says, “I dreamed of being the John Ford or John Huston of the ocean. To offer beauty to my fellow human beings.”

In a speech he delivered at the 1971 International Conference on Ocean Pollution in Washington, DC, Cousteau warned that “the sea today is in distress. We are facing the destruction of the ocean by pollution and other causes.” This led directly to the creation of the Cousteau Society, as well as a change in direction of his films from exploring life in the underwater world to dealing with “the fate of mankind.”

Though the world today seems to be precariously balanced on the edge of all sorts of environmental disaster, Becoming Cousteau ends on a high note. Asked, near the end of his life, if he is optimistic about our future, Cousteau responds “I am, because I have great faith in human beings, and I believe that some day people are going to evolve and begin to care.”

Ed Symkus has been reviewing films and writing about the arts since 1975. A Boston native and Emerson College graduate, he co-wrote the book Wrestle Radio, USA: Grapplers Speak, went to Woodstock, collects novels by Harry Crews, Sax Rohmer, and John Wyndham, and has visited the Outer Hebrides, the Lofoten Islands, Anglesey, Mykonos, the Azores, Catalina, Kangaroo Island, and the Isle of Capri with his wife Lisa.

His favorite movie is And Now My Love. His least favorite is Liquid Sky, which he is convinced gave him the flu. He can be seen for five seconds in The Witches of Eastwick, staring right at the camera, just like the assistant director told him not to do.

Thanks for this strong review of a film that matters to all.