Book Review: Man Ray — He Could Have Been a Contender

By Timothy Francis Barry

The biography raises the subject of Man Ray’s Jewish roots, but the matter is dropped pretty quickly.

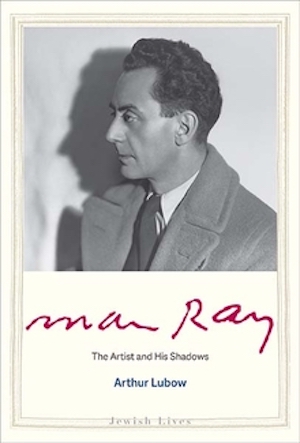

Man Ray: The Artist and His Shadows by Arthur Lubow. Yale University Press, Jewish Lives Series, 216 pages, $26.

Perhaps you’ve idly wondered just what it is that vaults one artist to the status of icon, while artists in a similar vein elicit little more than a shrug if their name is mentioned at all. Sales figures aside, it’s not an easy question. Compare and contrast Marcel Duchamp with Man Ray; Duchamp’s a figure of continuing and even growing importance, while Man Ray … well, if his reputation is not down for the count, it is receding into the dustbin of history. Will a new biography do anything to change this? Let’s leave it at “it can’t hurt.”

Certainly some provocative questions are raised, if not always answered.

In Arthur Lubow’s Man Ray: The Artist and His Shadows, we get a short (161 pages) yet vivid recounting of the life and times, though the times turn out to be more interesting than the life. For those of us who devoured all of the Paris-in-the-’20s material back in their school days, this will be familiar ground. Very nice to revisit it, of course: Man Ray photographing Kiki of Montparnasse as a cello — Le Violon d’Ingres, 1924; Man Ray affixing nails to an iron and calling it Cadeau (Gift), 1921; his splendid and still cutting-edge photographs and “solarized” photos — the rayographs.

And Lubow does have some worthwhile insights: that Ray is indeed a founding member of Dada; that his interchange of ideas with his close friend Duchamp “went both ways.” If Duchamp is the supreme innovator of modern art, one whose influence is still paramount today — then maybe we have to think about giving Man Ray a leg up in the pantheon.

The narrative Lubow unfolds is one of very diminishing returns for its subject. Ray (born Emmanuel Radnitsky in Philadelphia, 1890) began his art career very much on the come-up. He was on the ground running at the infancy of photography’s being accorded fine art status; he had work shown at the 291 Gallery, where Alfred Stieglitz (the man almost solely responsible for getting photos looked at as “art”) saw something fresh and new in the young scrapper’s images. And he taught the younger Ray “how to catch fish”; that is, how to go after the market.

Soon enough young Manny hies it over to Paris, where the fresh and new was breaking out. And, quite unlike the art world of today, wherein the young artist works toward an MFA degree, seeks fellowships, and hopes to garner a slot in a group show at a Lower East Side gallery, possibilities were rife in the Paris of the ’20s. Eric Satie is doing an atonal opera; he needs a set designer. A Polish count blows into town and opens a gallery — you got pictures to show? And we get quite a refresher course on the other players and their works: Meret Oppenheim, Tristan Tzara (“a Romanian Jew born Samy Rosenstock,” Lubow points out), Cocteau, Andre Breton, et al.

And he drops in the nugget that German artist Christian Schad had been making photograms, or camera-less photographs, before Man Ray jumped on the idea and made a career of it. So if one has always thought of Man Ray as a consolidator of others’ ideas — if a very energetic and often successful one — then this account doesn’t radically change that notion.

It wasn’t called The Roaring Twenties for nothing. Ray surfed this wave of everything-goes creative freedom, deftly cottoning on to the Dada movement, becoming part of the inner circle at the naissance of Surrealism. When Museum of Modern Art curator Alfred Barr Jr. mounted the first big show of this new movement in New York, Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism in 1936, Man Ray’s “enormous painting of Lee Miller’s floating lips dominated the entrance, and a rayograph appeared on the cover of the catalogue.” So, yes, Mr. Ray had his moments.

Ray’s later career trajectory could be termed Right Place, Wrong Time. He moved to Los Angeles in the ’40s, decades before the vogue for avant-garde artists arrived. Lubow’s account of this time makes for fascinating reading, however. Ray’s rich friend and supporter William Copley opens a contemporary art gallery largely on his enthusiasm for the artist’s work. The parties are epic; the sales almost nil. It goes on for two years and ends.

At the age when most artists are sifting through their yellowing press clippings, Ray moves back to Paris but, sadly, the parade has passed him by. The new flavors of Abstract Expressionism in America, and Art Informel in Europe are now the rage. He lives in a converted garage so poorly heated that he is reduced on frosty Paris winter mornings to making his sketches in bed, under a pile of duvets.

Man Ray, Cadeau (Gift), 1921.

There’s something undeniably sad and poignant about the artist slouching toward old age, still bent on making his paintings (which almost all critics would grade a B- at best, while his photographs rate a straight A.) He didn’t want to be a photographer; he shunned the offers to continue his fashion work, which had paid handsomely throughout the ’20 and ’30s. (The fashion work, ironically, is now being shown in museums, while his paintings gather dust in basement storage.).

His career enjoyed a revival of sorts — certainly he got some much-needed money out of it — around 1964, when Arturo Schwarz embarked on the enterprise of editioning the famous readymades of Duchamp (the bottle-rack, for instance) and also Man Ray’s early work. But, as Lubow points out, “many of the early objects exist only as photographic renderings; after taking the picture, Man Ray would discard what he had assembled.” Thus, “the editioned replicas of the blanketed sewing machine and the bound plaster torso turned these mysterious objects into souvenir trinkets.”

Ray found success, early on, certainly in spite of coming from a lowly ghetto background. But, while Lubow raises the subject of Ray’s Jewish roots, he also drops it pretty quickly. Did Ray suffer from anti-Semitic bias in his career? Seems not, but the question isn’t raised. He does touch on the phenomenon of 20th-century Jews Americanizing their names as they embark on entertainment careers — think Jerry Lewis, Lenny Bruce, Joey Bishop — ”shedding their telltale ethnic markings … as they strove to assimilate … cleansing of its east European and Semitic indicators.” But that’s on page seven, never to be mentioned again.

The Yale Jewish Lives Series is “interpretive biography … to explore the range and depth of the Jewish experience … and to illuminate the imprint of Jewish figures upon literature … the arts … sciences etc.” An admirable and interesting idea for a gamut of concise books whose subjects include Bugsy Siegel, Stan Lee, and Harvey Milk (not just the names you’d expect to see, like Martin Buber, Primo Lev,i and Elie Wiesel). But if this book’s central précis is, as it claims, to “use Man Ray’s Jewish background as one filter to understand his life and art,” that notion is little to be found in this book.

Tim Francis Barry studied English literature at Framingham State College and art history at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth. He has written for Take-It Magazine, New Musical Express, the Noise, and the Boston Globe. He owns Tim’s Used Books and TB Projects, a contemporary art space, both in Provincetown.

Tagged: Arthur Lubow, Jewish Lives Series, Man Ray, Timothy Francis Barry

You have no substantive knowledge of Man Ray and his superb and groundbreaking work. Look at the bounty of major museum exhibits, including the just about to close “Man Ray, The Paris Years” at the Virginia Museum Of Fine Arts. Not to mention high yield major auction sales of Man Ray’s work. Lubow, while knowledgeable, is a lightweight regarding Man Ray scholarship. Try the Neil Baldwin biography and the numerous well researched books on Man Ray.

Publishing an article as an opinion would be not great, but acceptable. Your tone as one with expertise doesn’t cut it.