Film Interview: “Searching for Mr. Rugoff” — A Passion for Independent Cinema

By Glenn Rifkin

A documentary about a “crazy genius,” theater owner and film distributor Donald Rugoff, a difficult but insatiable P.T. Barnum-like impresario whose storied rise and tragic fall in the movie business has been overlooked.

Searching for Mr. Rugoff, directed by Ira Deutchman. (opening at the Coolidge Corner Theater on Aug. 20)

Arts Fuse review

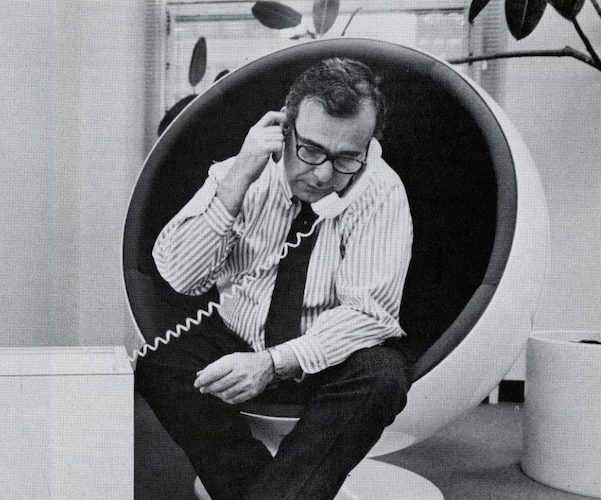

A scene featuring the subject of Searching for Mr. Rugoff.

If, like me, you were lucky enough to be a movie buff in the late ’60s and ’70s, the emergence of a vibrant art cinema landscape shaped the core of our lifelong passion for movies.

The offerings included a stunning variety of foreign and domestic independent classics: dramas and documentaries, such as Z; Putney Swope; Endless Summer; The Garden of the Finzi-Continis; Swept Away (By an Unusual Destiny in the Blue Seas of August); Harlan County, USA; The Man Who Loved Women; Pumping Iron; Monty Python and the Holy Grail; and Gimme Shelter. We were introduced to directors Costa-Gavras, François Truffaut, Werner Herzog, Milos Forman, Lina Wertmüller, and a host of other cinematic icons whose influence reached all the way to Hollywood and ushered in a renaissance of innovative, award-winning independent filmmaking.

The “crazy genius” who brought all these films into the mainstream was a theater owner and film distributor named Donald Rugoff, a difficult but insatiable P.T. Barnum-like impresario whose storied rise and tragic fall in the movie business was seemingly forgotten. Long before Miramax and the Weinsteins, the studio classics divisions, and the vibrant indie film community, Rugoff, with his Cinema 5 film distribution and exhibition company, pioneered the concept and midwifed the birth of that community. He not only bought and distributed all the above-named films, among hundreds of others, but he owned several of the Upper East Side art house theaters in Manhattan — the Beekman, Sutton, Plaza, Paris, Cinema I and II, among others — that became meccas for long lines of enthusiastic film buffs eager to devour such esoteric fare.

Rugoff created his own wild and unconventional advertising for every film, garnering widespread attention that generated plenty of buzz. From 1965 to 1978, Cinema Five films received 25 Oscar nominations and six wins.

Given his impact, Rugoff should have become a legend alongside the Mayers, Warners, and Redstones. Instead, his story was lost … until now. Ira Deutchman, an indie film industry heavyweight himself and a former Cinema 5 employee, has released a fascinating documentary called Searching for Mr. Rugoff. In it, Deutchman sets off on a worldwide quest to find out what happened to Rugoff as his career descended into irrelevance and he died in obscurity on Martha’s Vineyard at age 62.

Deutchman only worked for Rugoff for three years, but credits the gruff, disheveled, and quirky boss as the source of nearly all of the important lessons he learned about the independent film business. Deutchman, a film professor at Columbia University, has spent more than four decades making, marketing and distributing films such as Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho, Robert Altman’s The Player and Short Cuts, and the award-winning documentary Hoop Dreams. His companies, Cinecom, and later Fine Line Features, helped define the independent film industry. Deutchman spoke to the Arts Fuse about his film, which marks his directorial debut.

Arts Fuse: Where do you put Rugoff in the pantheon of the greats on the business side of the film industry?

Ira Deutchman: He was an extraordinarily important figure, a transitional figure. I would definitely put him in that pantheon. There was a moment in the film business where things were literally transforming from the major studio era to what became the independent film era. The ways Rugoff did business made him incredibly important. Along with his bluster, he looked in the oddest places both for films he would distribute and for the ways he would distribute them and market them. He looked at the world askew and somehow saw things that other people didn’t see. And, as a result, he stumbled upon a way of reengaging audiences at a time when audiences were being lost to television. It ended up affecting the business in subtle as well as in pretty massive ways.

AF: To what do you attribute Rugoff’s obscurity? He was a major figure in the film industry at the time. How is it that film buffs never heard of him?

Director Ira Deutchman

Deutchman: Back in those days, it was not quite the parlor game among the mainstream — that it became later — to keep track of the film business. People in the business would know who these characters were, but the general public didn’t hear about people who were more behind the scenes. Years later, when mainstream publications like the New York Times started printing the weekly grosses in the way they offered sports scores, it actually changed the nature of how consumers tracked the film business. That’s one reason. The other was that Rugoff was never a publicity seeker. I don’t know, maybe it was because he was not fond of the way he looked and sounded, but there is virtually no footage of him available. He seemed to avoid things like that. The final reason, perhaps the most important, is the fact that he was such a nasty guy. He burned every bridge that you could imagine.

Once he was kicked out of his company and didn’t have its powerful platform any longer, nobody wanted to hear from him. He just drifted off into the background.

AF: Any examples of that bad behavior, aside from insisting that everyone call him Mister Rugoff, that you observed when you worked there?

Deutchman: He had very high standards for everything and he was always right. Employees would be dressed down constantly for the slightest little things that they didn’t do exactly to his specifications. He had to hire secretaries almost daily because he would berate them so much they would quit. His was the behavior of a very unstable person.

AF: And yet he was able to woo some of the most iconic filmmakers of all time. Was he able to switch on the charm when he was with them?

Deutchman: Yes. In fact, most of the filmmakers were only peripherally aware of how abusive Rugoff could be to his employees and people who worked for him. The one taste they would get: it was fairly common that even famous filmmakers were made to wait for hours for Rugoff in the reception area.

AF: Did you have trouble convincing people like Costa-Gavras and Lina Wertmüller, to talk to you about this guy?

Deutchman: In both cases, when the interview began, they were somewhat skeptical of my motives. I was able to put their minds at ease by telling them I worked for Rugoff. I didn’t have any agenda regarding how I was going to portray him. I got them to relax and open up. In other cases, with some former employees, I did have trouble convincing them. When I finally reached them, and tried to convince them they should go on camera, a lot of them were shy about being filmed. Some were worried they wouldn’t remember enough — although it often came flooding back when they started talking. Some refused to talk to me. There were people who worked with him and knew him and really didn’t want to go down that road.

AF: Whose work did you emulate as you made this film?

Deutchman: I don’t know that there’s a particular documentarian I can point to as the stylistic inspiration. I was more influenced by recent podcasts. In terms of tone, I had in the back of my mind the podcast Serial, and the way they tell their stories. It’s not 100 percent linear, and yet the narrative is structured in a very compelling way. It’s one of the reasons I ended up erring on the side of including more talking heads. The style of documentary that’s come into vogue these days is to avoid talking heads at all costs. It’s not visually interesting enough. You should do recreations and all that kind of stuff. I just felt, viewing the footage, that it was way more compelling when I watched people telling their stories. They were all such good storytellers.

The subject of Searching for Mr. Rugoff.

AF: What do you hope people take away from the film?

Deutchman: It comes down to thinking outside the box about the dilemmas we face about reaching audiences. There is a tendency, and I’ve felt this way for a while now, even before the pandemic, that distributors and exhibitors are admitting defeat: “Oh well, I guess theatrical moviegoing is over.” I’m hoping that the example of Rugoff and his history will show people that we’ve been through cycles like this before. The way forward means discarding what is not working now and thinking ahead to what is different. What is it that can capture people’s attentions and imaginations that’s different from anything that’s out there at the moment? What can entice people to come back to movie theaters again? It’s almost exactly the same circumstance now as in the late ’50s and early ’60s, when people were talking about the demise of theatrical moviegoing because everybody had a TV. Rugoff realized that the way to get people back into the movie theaters was to provide provocative, interesting, and out-there kinds of movies that could not be seen on TV. Today’s malaise is not necessarily the same thing — but it’s related. What can movie theaters give people that they can’t get at home?

AF: You are adamant that seeing a movie in a theater remains a singular experience.

Deutchman: Seeing a movie in a theater demands your undivided attention. You don’t have a remote control in your hand and you have turned your phone off. That changes the experience: you are forced to to focus on what’s on the screen when you give up the kind of multitasking you do at home. That opens things up, presents a different kind of cinema experience. You are invited to look more deeply into what you are watching and experience things in a very different way.

Glenn Rifkin is a veteran journalist and author who has covered business for many publications including the New York Times for nearly 30 years. He has written about music, film, theater, food and books for the Arts Fuse. His new book Future Forward: Leadership Lessons from Patrick McGovern, the Visionary Who Circled the Globe and Built a Technology Media Empire was recently published by McGraw-Hill.