Author Interview: “Of Thee I Sing” — Ben Railton on the Cycles of American Patriotism

By Blake Maddux

“If you are more critical or try to highlight some of the worst things that happen in America, then you are un-American or anti-American.”

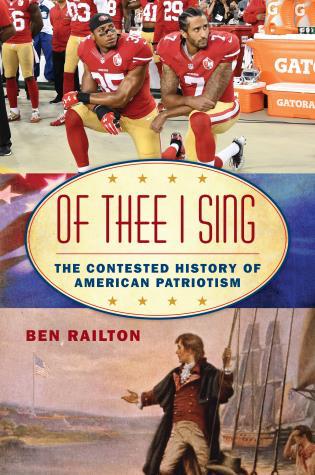

Of Thee I Sing: The Contested History of American Patriotism (The American Ways Series) by Ben Railton. Roman & Littlefield, 214 pp., $36.

As a scholar and author, Ben Railton has written books about American patriotism and identity in general and the Chinese Exclusion Act and Gilded Age culture more specifically. As an educator, he has been “very happily” employed since 2005 by Fitchburg State University, where he is a professor of English Studies and the coordinator of the American Studies program.

When he is not writing books or teaching classes, Railton is maintaining his 10-1/2-year-old daily blog or composing his monthly Saturday Evening Post column.

Finally — and presumably foremost — he is the father of two teenagers, Aidan and Kyle, who were (fortuitously for me) away at summer camp when I spoke to him by phone about his most recent book.

The Arts Fuse: You wrote another book for The American Ways Series called We The People: The 500-year Battle Over Who Is American. How do that book and Of Thee I Sing complement one another? Are they two halves of a whole?

Ben Railton: [We The People] was about how we define America. The competing definitions and visions of what “America” is, what “American” is, what it means to be a part of this place. A lot of that is connected to and implicated in something like patriotism. What it means to love a place, to feel loyalty to it, or to care about it is so caught up in what we mean by that place and how we think about it. So it was kind of a natural complement in that way, thinking not just about the place but our connection to it, our perspective on it, and our idea of it for ourselves and collectively.

Of Thee I Sing focuses a little bit more on how those debates over how we define America and who we are are so fraught and so tense in part because if you are more critical or try to highlight some of the worst things that happen in America, then you are un-American or anti-American. That got me thinking about the ideas of mythic and critical patriotism a little bit more.

AF: Your PhD is in American literature and you teach several classes related to that subject. How did you end up writing books coverning centuries of American history?

BR: The full arc of my own thinking, identity, and scholarship has been fundamentally about American Studies and combining disciplines. Growing up in Virginia, I was obsessed with history, but I also read and wrote all the time. Early on I was trying to combine history, literature, and writing. My undergraduate major [at Harvard] was something called History & Literature and my graduate advisor in the English department was the American Studies chair and founder at Temple University. I try to bring that interdisciplinary perspective to everything that I teach and do. The other thing that I am interested in is the idea of narratives, the stories that we tell, and the way we create those stories. A lot of history, patriotism, and education are at least as much about the shapes of the stories and narratives we’re creating as they are about the content itself.

AF: Are specific demographics more likely to align with a specific form of patriotism? And is that a problem?

BR: I would say that what I came to define as mythic patriotism, the one that I am most critical of and find the most divisive and often disruptive, has been most closely tied to the white supremacist visions of America. The set of myths about a fundamentally white America is integral to how I define mythic patriotism because the power structure has been white and male for so long. So I do think that a lot of the thinkers and voices in that mythic patriotic lens have been part of that white supremacist power structure in America.

That means that the other categories, particularly active and critical — which are opposed or alternatives to mythic patriotism –have very frequently been modeled by Americans who were disenfranchised, including Americans of color, women, and communities such as LGBTQ.

Scholar and author Ben Railton

AF: Along similar lines, do the forms of patriotism have direct counterparts on the political spectrum? Is one more likely to be on the left or right (or in the center) of the political spectrum depending on the kind of patriotism one subscribes to?

BR: I grew up in the South, and the Democratic Party was the party of white supremacy there for a century. So there’s no clear alignment across history. I absolutely think it’s true in 2021 that the current GOP has attached itself almost entirely to what I call mythic patriotism. As such, anyone who is practicing critical patriotism — such Gwen Berry or Colin Kaepernick or Alexander Vindman — in this current moment is perceived to be a leftist or a Democrat. My ultimate goal would be a way to see these types as not about partisan politics, but about ways that we can all participate in our civic and national community in meaningful, productive ways. I do think that if it gets too limited to partisan politics, which is currently happening, it becomes that much harder to get toward a place that can be inclusive and allow for active and critical patriotism. I don’t think it has to be that limited.

AF: Have some patriotic ways been more prevalent in certain eras of history than in others?

BR: The early 20th century, the period around World War I, has this incredible range of mythic patriotism in terms of expressions, texts, and histories. It inspired a kind of a cycle, moments when these narratives of mythic patriotism — “you’re with us or you’re against us,” when any critic is an enemy of the United States — really take hold again. War and other national trends can contribute to it. Those moments also generate challenges that set active and critical patriotic resistance against that deepening, hardening mythic patriotic divisiveness.

AF: In what ways can patriotism be both a dividing and uniting force?

AF: In what ways can patriotism be both a dividing and uniting force?

BR: That’s a question I’ve thought a lot about in recent years. I really love the bumper sticker “God Bless the Whole World. No Exceptions!” Phrases like “God Bless America” miss out on the ways that we’re all connected and part of the human race. One thing I try to do in my own thinking is to separate patriotism from nationalism. By nationalism, I mean American exceptionalism, perspectives like “we’re the best country in the world,” “my country right or wrong,” us versus them, God Bless America. Those phrases chauvinistically privilege this nation and that’s really dangerous. After separating them, what I then try to think about are the benefits of shared pride in a community. Patriotism doesn’t have to be any different — except for in scale — from shared pride in a hometown or in an institution that we attended as students or work at or belong to. That would make patriotism a more positive source of shared meaning in our lives or collective experience rather than a matter of labeling other places as being worse or as our enemies. Instead, we can recognize that a place is ours and that there are things that we share that we can build on. There is value in embracing the best of a shared space and moving that best forward.

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who regularly contributes to the Arts Fuse, the Somerville Times, and the Beverly Citizen. He has also written for DigBoston, the ARTery, Lynn Happens, the Providence Journal, The Onion’s A.V. Club, and the Columbus Dispatch. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife and one-year-old twins—Elliot Samuel and Xander Jackson—in Salem, MA.

Thanks so much for your work, Blake! Just a note to everyone that I’d love to chat more about the book and the contested histories of American patriotism; feel free to send me an email (brailton@fitchburgstate.edu) with any ideas for such conversations!

Thanks,

Ben

My pleasure, Ben. Thanks so much for talking to me about the book!