Arts Feature: The Lockdown Underground — Discoveries in Isolation

By Milo Miles

Stuck in a world where regular shopping was rare and live performances extinct, the right path seemed to be the curls and swirls of mentions and references that led to surprising new or little-known artists and fascinating new levels of famous ones.

Take the almost giddy interview with John Swartzwelder that appeared in The New Yorker.

I’m a formerly passionate “Simpsons” fan, but this guy had never made a blip on my radar. Then, sniffing around, I discovered that before he ever touched a TV script, Swartzwelder wrote a humor book with of delightful off-beat concept:

Hell, it’s at least as recommended as any “Simpsons” episode, since it has a pure distillation of the wise-guy absurdity (and satire of oh-so-serious science publications) with droll, precise illustrations to match, every time out. The final weird note is that, far as I can determine, David Schutten has not illustrated anything else. Can that be possible?

What also seemed unlikely but amazing was the note on the very last page: “Made in the USA, Middletown, DE, May 02 2021.” This was a book printed up and bound on demand!

I also delighted in another quickie-print book around the same time, A Compendium of Margaret St. Clair.

I was less happy with another quickie-print book. I had long sought after the novella “The Princess and the Goblin” (1872) by George MacDonald and out of nowhere found out it was just out in The George MacDonald Fantasy Collection. I never finished reading my lost gem. The print was so tiny and the layout so plain and dense that it was as depressing as reading off a screen and more of a chore.

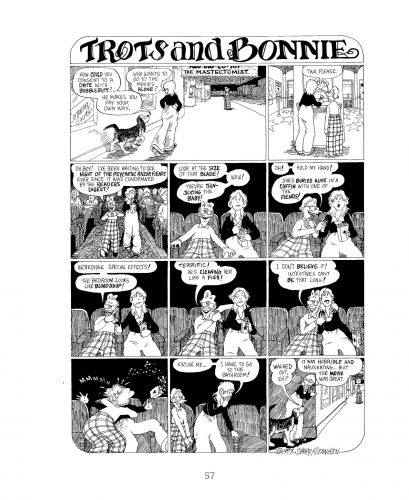

The complete opposite graphic delight from the same period was the first American appearance of a Trots and Bonnie anthology. Can’t emphasize enough how much Shary Flenniken’s commentary on the comics and their times add to the delight and enlightenment of the book. (Plus — good for her leaving out the works that have not aged well. Satire can indeed turn sour.)

Then Flenniken delivered an underground jolt I did not see coming at all. She cited newspaper cartoonist H. T. Webster as a major influence and I’m like “Who??”. Rooting around in the back aisles of used books for sale online, I found The Best of H. T. Webster (Simon and Schuster, 1953). Obviously, Webster was quite well known around the time I was born but has turned invisible in the years since. And once you look at the strips he’s an undeniable mentor to Flenniken, down to the sardonic attitudes and some dogs that are plainly ancestors of Trots.

Must honor the soul of a creator with the last lines from Flenniken’s “Author’s Notes” about working in the ‘70s and ‘80s:

“During much of that time though, a magazine or comic was not a collector’s item. I never expected my work to be relevant or even around decades later. I thought we would all be better by now.”

To finish the graphics section of the Lockdown Underground, I mention a “fine art” strangeness I’ve known for a long time and a terrifying new discovery. Worthy pondering just how rarely “serious” artists depicted the most dire topic of the Fallout Shelter age.

Another inspiration also came from Death — when the long-celebrated writer Larry McMurtry passed away early this year, I ran across more than one suggestion that the collection of essays In a Narrow Grave (first published in 1968, but tweaked several times until 2018) was his finest nonfiction work. I absolutely agree. Subtitled “Essays on Texas,” the barely 200-page book shows how wide a territory that can cover. It’s ultimately about the final decline of the cowboy, but McMurtry rides across the range, all the way to Hollywood even with the amazing “Here’s HUD in Your Eye.” Among many outstanding points, McMurtry underscores why Hud is an erroneous title for the flick (even if Paul Newman is nowadays the only remembered actor). Hud is a real bad guy in the story, indirectly responsible for the death of the incarnation of old-time American West values, his father. (I must add that another McMurtry-authored movie, The Last Picture Show, is by far the most vivid and precise presentation of growing up in small-town Western US during the ‘50s and ‘60s. Gets every tone and passion right.)

Other mind expanders are essays on the history of Texas literature, how a thoroughly non-cowboy grew up amidst cowboys and plain eccentric relatives and why cowboys get along better with horses than women. One dedication in the book is to James McMurtry, Larry’s son, who happens to be a tremendous songwriter, musician, and bandleader. I recommend Live In Europe, and if you like that well enough you’ll want everything. James has a new album coming out at the end of August.

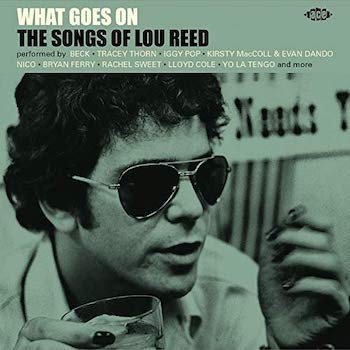

Which leads to the subject of music and slipping into my very comfortable grumble and gripe mode for a moment, I note that I utterly despise the current mad fashion for 10- 20- 30- 50th Anniversary reissues of famous records with overly fancy packaging or just in colored vinyl for the first time or gaudy limited editions of any kind. I got into popular music and jazz to hear the sound of tomorrow, not munch on the past. (Though there are a number of critics who excel at that and I insist it is necessary to understand as much of music history as you can in order to apprehend the sound of tomorrow.) Even so, one of my favorite discoveries of in the Lockdown Underground was a brilliantly selected and sequenced collection of oldies, and cover versions at that.

What Goes On: The Songs of Lou Reed (Ace) Includes a host of surprising performers — Beck, Lloyd Cole, Rachael Sweet, Tracey Thorn — but every track clicks and showers hosannas on the songwriter as well as the performers. Two final pluses: The set includes “Rock ‘n’ Roll” done by Detroit featuring Mitch Ryder, which I think beats the original, one of Reed’s most unleashed works. Forget rock ‘n’ roll — this version will save your life. And in the CD booklet, you get to see the cover of the pornographic paperback, The Velvet Underground, which inspired the band name. (The only copy of it I ever saw was going for a bazillion dollars in a used book store because the owner understood its significance.)

What Goes On: The Songs of Lou Reed (Ace) Includes a host of surprising performers — Beck, Lloyd Cole, Rachael Sweet, Tracey Thorn — but every track clicks and showers hosannas on the songwriter as well as the performers. Two final pluses: The set includes “Rock ‘n’ Roll” done by Detroit featuring Mitch Ryder, which I think beats the original, one of Reed’s most unleashed works. Forget rock ‘n’ roll — this version will save your life. And in the CD booklet, you get to see the cover of the pornographic paperback, The Velvet Underground, which inspired the band name. (The only copy of it I ever saw was going for a bazillion dollars in a used book store because the owner understood its significance.)

Another way to be timeless is to be unique, and that certainly applies to Peter Stampfel’s 20th Century in 100 Songs (Louisiana Red Hot). One advantage of writing today is that I don’t have to take up line after line explaining who Stampfel is — look him up on the interwebs. (You should know him on general principle, since he’s been an ideal outsider for ages.) The concept here is one song from each year of that 20th century in chronological order. Has to be a freaked-out mess, right? How can you go from “Take Me Out To the Ball Game” to “Charleston” to “Night Train” to “Dancing With Myself” with stops for unknowns like “Love on a Greyhound Bus?” The closest I can come to an explanation is that Stampfel and his perfectly compatible fellow players approach every work as a kind of folk song but infuse them with a brio that can be sad or sexy or party-hardy or just timeless weird. Get this and you will forever have a “hey, wanna hear a strange but cool record?”

Carrying a two-ton past can make it tough for a style of music to thrive in the present. Every year I hear blues records with sometimes ace playing but tired topics. Big exception in lockdown was veteran Guy Davis’s Be Ready When I Call You (M.C.). Starts with an arresting absurdity, “Badonkadonk Train,” but jolts you with contemporary political meditations like “God’s Gonna Make Things Over” (Tulsa massacre) and “Palestine, Oh Palestine” (calm and thoughtful). Throw in a sassy and arch remake of the classic “Spoonful” and you have the blues album of at least this year.

I get an email every time some performers burp, but I somehow got through the first half of the Lockdown without hearing anything about Rina Sawayama’s Sawayama (Dirty Hit). Then I saw a remarkable article about her and Elton John. They even perform a lovely duet version of one of her songs.

More than the obvious “if you like Elton John you’ll like Rina Sawayama,” she has a relentless flair for lust and romance, a fondness for the f-word and gnarly guitar breaks. My choice for the all-time Lockdown Rock ‘n’ Roller.

Milo Miles has reviewed world-music and American-roots music for “Fresh Air with Terry Gross” since 1989. He is a former music editor of The Boston Phoenix. Milo is a contributing writer for Rolling Stone magazine, and he also written about music for The Village Voice and The New York Times. His blog about pop culture and more is Miles To Go.

Tagged: "Sawayama", A Compendium of Margaret St. Clair, Be Ready When I Call You, Guy Davis, In a Narrow Grave, James-McMurtry, John Swartzwelder, Larry McMurtry, Live In Europe, Lou Reed, Milo Miles, NYRBooks, Peter Stampfel’s 20th Century in 100 Songs, Rina Sawayama, Shary Flenniken, The Best of H. T. Webster, Trots and Bonnie anthology: