Arts Remembrance: Pianist-Composer Frederic Rzewski

By Steve Provizer

I consider composer Frederic Rzewski the most profound and persistent explorer of how to address injustice through the use of sophisticated compositional tools.

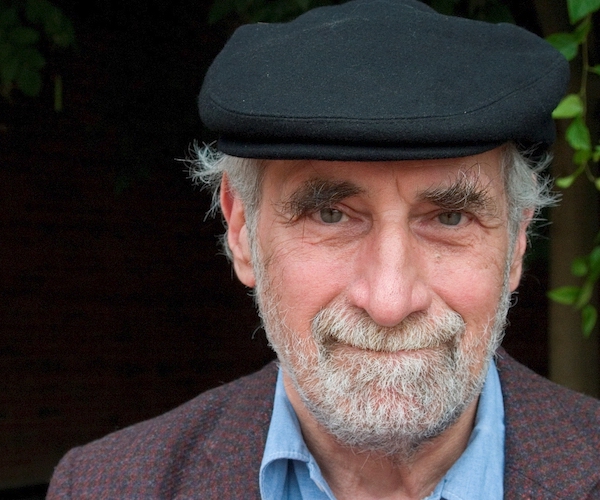

Frederic Rzewski at 80. Photo: Michael Wilson.

The recent death of pianist-composer Frederic Rzewski at the age of 83 on June 26 triggered memories of my time spent with him and other “new music” luminaries at a 1973 event called New Music in New Hampshire (NMNH). I’d like to take this opportunity to look at a singular event and figure in American musical history.

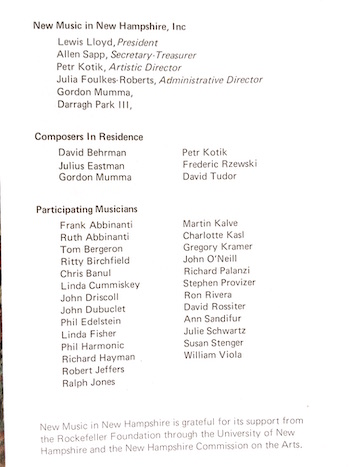

David Tudor, Gordon Mumma, Julius Eastman, Petr Kotik, Alvin Lucier, and Frederic Rzewski were listed as artists-in-residence on the notice for NMNH I saw posted on a bulletin board in the music department at Wesleyan University. Tudor had the biggest reputation because of his long-term collaboration with John Cage, but they were all important contributors to the new classical, electronic, electro-acoustic, and avant-garde music of the era. Rzewski shared the exploratory sensibility of his cohort, but was set apart from the others by his determination to fuse the musical and the political.

NMNH was held on the grounds of Stafford’s in the Field in Tamworth, NH, which contained a large central inn, a few small out-cabins, and an oversized, three-story barn. Nestled on a rise at the edge of a forest near Mt. Chocorua, the setting was bucolic. A walk through the woods to a chilly stream for a quick skinny dip provided daily relief. The event was nonhierarchical, with no obvious difference maintained between the artists-in-residence and the 20 other musicians who attended. And yes, in retrospect, although about a third of the other musicians were female, the omission of women as artists-in-residence is striking. Instruction was minimal, although knowledge of electronics was crucial. I seem to recall a class devoted to soldering circuitry. Time was mostly spent in small, shifting groups, developing music that would be presented in a series of concerts.

From the 1973 program for New Music in New Hampshire (NMNH). Photo: Steve Provizer.

Tellingly, for an event boasting so many heavy-hitters, a recent search on the Internet yielded a total of two references to NMNH. Both of these were to a piece called “Sliding Pitches in the Rain Forest.” Several composers collaborated on this composition, which was initially put together by Tudor for the Merce Cunningham dance troupe in 1968. Various objects were hung and placed throughout the space. Transducers were attached to the objects that induced sound resulting from the resonances of the objects. Listeners interacted with the piece as they wandered through it.

(Other music performed at NMNH included: a piece by Kotk, played continuously for 20 minutes, that was based on the eye movements of drunken rats in a maze and a work that involved dropping objects from the second story of the barn onto electrified, amplified bed springs. I played a solo trumpet piece on the grounds of the inn which involved pointing the horn in several different directions in order to generate the different echo offered by each direction. One piece, carefully plotted by Eastman, involved five of us each controlling five (as I recall) metronomes. The result was 20 metronomes that for some mysterious reason synchronize themselves. An all-day reading was called “Gertrude Stein in Chocorua.” Rzewski played Cage’s “Concerto for Piano and Orchestra” and we also performed Cage’s “Atlas Eclipticalis.” One very elaborate piece entailed a few of us brass players driving to another hill a few miles away and climbing to the top. A person holding semaphore flags came with us. Back at the barn, several amplified flutists were sitting with their own semaphore person. The groups played antiphonally over the two hills, their sounds triggered by the semaphore signals. Interestingly, when we climbed down from our hill the local sheriff was waiting to greet us. He demanded our ID — someone living in between the hill and the barn had complained about the noise(!).

I played in many of these pieces as well as in an improvisational ensemble led by Rzewski. The organizing premise was that anyone could stand up in front of the group and conduct; people would evoke with their bodies what they wanted the group to play. Although the musicians at NMNH were skilled players, few were grounded in improvisation. Not to put too fine a point on it, but there was too much playing and not enough listening and silence. Rzewski didn’t take an active role; he certainly never criticized anything we played. At the time, I didn’t know what credentials he had that qualified him to lead such a project. It was only after the fact that I learned of his deep roots in group improvisation and of the full scope of his accomplishments.

It’s only a snapshot from a time long past, but I remember Rzewski as a slim, wiry man, slightly stooped, as are many pianists. He often had a pipe in his mouth, lit or unlit, and chose his words carefully. While he sported a Mao cap and carried a copy of Mao’s Little Red Book, I experienced no political pedantry or proselytizing. His compositions were the stage on which he explored how to bridge activism, political philosophy, and music.

Rzewski was a virtuoso pianist who wrote mostly piano music, although he also composed for piano and orchestra, voice, and various-sized ensembles. His compositions drew on all the musical resources Western composition offers — from Bach to Webern and the Minimalists. Rzewski brought improvisation back to “classical” formats by creating opportunities for elaborate improvised cadenzas into his compositions.

In Rome in 1966, he was one of the founders of a group called Musica Elettronica Viva, which put myriad musical resources (acoustic and homemade electronic instruments) into play for group improvisation, including chants and drones. The collective was known to invite the active participation of audiences.

In the early ’70s, Rzewski became involved in the Musicians Action Collective, a coalition that organized benefit concerts for United Farm Workers, a defense fund for Attica inmates, and the Chilean solidarity movement. This led him to write “El pueblo unido jamás será vencido” (The People United Will Never Be Defeated). This hour-long composition includes 36 variations and was composed for the pianist Ursula Oppens in 1975. Extra-musical resources are put into play; for example, the pianist whistles, shouts and slams the lid of the instrument. But there is nothing dumbed-down about this composition. It is stirring, provocative, and challenging. He wrote “Coming Together,” a setting of letters from Sam Melville, an inmate at Attica State Prison, at the time of the 1972 riots. Rzewski described the Attica rebellion as an “atrocity that demanded of every responsible person that had any power to cry out, that he cry out.”

His composition “North American Ballads” (1978–79) is based on and develops traditional tunes as well as labor-inspired material: “Dreadful Memories,” “Which Side Are You On?” “Down by the Riverside” and “Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues.” The latter is an astonishing piece, calling for extreme pianistic technique and considerable endurance. There are several versions on YouTube.

Like others in his avant-garde cohort, Rzewski operated almost completely outside the commercial marketplace. He was supported financially by commissions, performances and — although I don’t think he was an academic type by temperament — by teaching in European and US academic institutions. I have read that he could be very harsh with students.

His compositions are sometimes accessible, but often difficult and abstract. Rzewski well understood the paradox of purveying a populist-activist agenda while assuming a high level of musical and political sophistication on the part of the audience. When asked if he thought it was possible to affect politics through music, Rzewski replied: “Probably not, but you have to write as if you could. You can’t be sure. You might.” Speaking of his work in the ’60s, Rzewski observed: “Free improvisation was going to change the world. It was going to create an entirely new language, so that people could come together from different parts of the planet and instantly communicate.…Well, of course, we were wrong.”

“Preparation for Rainforest IV at New Music in New Hampshire, July 1973″ taken in the barn Photo: Gordon Mumma/MOMA

In general terms, Rzewski’s work, like that of his peers, operated in an artistic space carved out by Cage and European modernists like Berio, Stockhausen, and Xenakis. It was an eclectic space that drew on several artistic disciplines and philosophical premises — especially from the East. The sounds were diverse, but the underlying principle was exploration — albeit without overt self-expression. Another essential element, for many, was indeterminacy. Rzewski was at home with this distanced aesthetic, but only up to a point. He wanted to use all the arrows in the modernist quiver, but his music reflected a belief that political awareness and concrete action were as –if not more — fundamental than acts of personal and/or abstract investigation. In addition, rather than taking up the cause of indeterminacy, Rzewski stuck with Western musical notation. He was only interested in indeterminacy when it arose within the bounds of group and individual improvisation.

I consider Rzewski the most profound and persistent explorer of how to address injustice through the use of sophisticated compositional tools. Whether these tools can succeed is, of course, open to debate. “Music doesn’t require a text,” Rzewski explained. “It does, however, require some kind of consciousness of the active relationship between music and the rest of the world.” This may be the quixotic sentiment of someone walking against a wind — if not a strong gale — but very few have walked the walk as he did.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Tagged: Frederic Rzewski, Musica Elettronica Viva, New Music in New Hampshire

Thank you for this – it really opened my eyes, ears, and mind to a composer I had not known enough about. The embedded performance by Gilles Vonsattel is a stunner. I had first heard this pianist’s musicianship at the Rockport Music Festival and was greatly impressed.

So – a really valuable article in several ways. Long live the music of Rzewski!

John W. Ehrlich

John-Thank you and thank you for your fine work with The Spectrum Singers.

Insightful and cogent.I had done a premiere with Cage in Toronto during the US bicentennial and your overview reminds me of the discipline and expanded approach that John Cage & Rzewski to music and social issues.

Thanks – an interesting essay describing what must have been an exciting time musically in New Hampshire in 1973 – Rzewski, Mumma, Tudor, Eastman, Kotik, Behrman, as well as “students” who went on to be well known in music circles. I have a great photo that Mumma took of Susan Stenger and Julius Eastman.

Thank you. Your experience there was something special to that time and moment, and you describe it vividly.

Oh, this is sad news to me.

I met Rzewski just once and he was very warm and gentle.

A giant has passed from a time of tremendous innovation. I fear we will never see its like again.

Thanks for an excellent article.