Book Review: “The Anglo-Saxons” — An Era of Continual Turmoil and Buried Treasures

By Thomas Filbin

Medievalist Marc Morris has written an engaging account of turbulent times in a suitable and interesting style.

The Anglo-Saxons by Marc Morris. Pegasus Books, 508 pp. $32.

A vast history of England, from the fall of Rome to the Norman Conquest, lay ready to be unearthed, both literally and figuratively. The opening of medievalist Marc Morris’s latest book recounts the discovery of a treasure trove of coin, gold, and artifacts found by accident in Suffolk by someone with a metal detector who was looking for a lost hammer. (Morris notes in a dry aside that the hammer was also found. It is clear from the outset that his tale will be one of the extraordinary superimposed over the ordinary). Revelatory things are all about us if we take the time to look. The early history of England was replete with invasions whose enthusiastic actors were constantly looking to pillage and loot. Burying your valuables to be dug up later was the only secure way to retain them. Morris estimates that thousands of these treasure hordes in Britain are now being discovered with regularity.

A vast history of England, from the fall of Rome to the Norman Conquest, lay ready to be unearthed, both literally and figuratively. The opening of medievalist Marc Morris’s latest book recounts the discovery of a treasure trove of coin, gold, and artifacts found by accident in Suffolk by someone with a metal detector who was looking for a lost hammer. (Morris notes in a dry aside that the hammer was also found. It is clear from the outset that his tale will be one of the extraordinary superimposed over the ordinary). Revelatory things are all about us if we take the time to look. The early history of England was replete with invasions whose enthusiastic actors were constantly looking to pillage and loot. Burying your valuables to be dug up later was the only secure way to retain them. Morris estimates that thousands of these treasure hordes in Britain are now being discovered with regularity.

The medieval world of the Monty Pythons satirized the period’s class, religion, superstition, innocence, and even death. But serious works on medieval history go deeper and force us to consider our perpetuation of past foibles and beliefs, though we imagine we have left them far behind. Power and warfare are as intrinsic to the present as they were 15 centuries ago; looking at “then” will hopefully make us more aware of “now.”

Roman Britain was a civilized place with legions in place to secure its order. Morris estimates that 10 percent of Rome’s armies, about 50,000 men, were garrisoned in England. Towns were prosperous and the Anglo-Roman upper crust enjoyed villas worthy of Rome. By the second and third centuries, however, danger from invaders crimped that comfortable future. Raiders from across the water ventured beyond the Rhine and the Danube. Hadrian’s wall was unable to hold back the Picts, the indigenous people of Scotland, who originated in Scandinavia. When the Roman Empire collapsed and its army was withdrawn, England began a descent into fractured kingdoms and wars intended to repel attacks. Foreign invasions were a periodic nuisance until a turning point arrived in 793 when “the heathen men” attacked the monastery at Lindisfarne. From then on it was total war. Strategies varied, from fighting the invaders, paying tribute, or outright bribing them to keep their distance. By the late ninth century the Danelaw was created, formalizing Scandinavian rule in parts of England.

Angles, Saxons, and Jutes were the three major strains of people in England and the land was divided into seven kingdoms: Kent, Sussex, Wessex, Essex, East Anglia, Mercia, and Northumbria. It is interesting that the first three names exist today as titles for the Windsor family (or Battenbergs, if you prefer). England respects nothing more than links with tradition — they firmly establish authority.

Morris takes us through various epochs of English history, much of it determined by whether kings were strong or weak, wise or foolish. Three rulers who presided over the unification of the island into a central kingdom were Alfred the Great (d. 899), Aethelstan (d. 939) and Aethelred the Unready (d. 1016), tarred forever by a bad translation of the old English word “unraed,” which properly means “poorly advised.” Creating unified laws and currency and beating back the Danes occupied much of that era.

An interesting theological/political sidebar to the invasions is what Morris calls the Anglo-Saxons’ adoption of a “victim-blaming position ever since the Vikings had made their first appearance.” Christian writers of the time believed that “If God was in charge of human destiny, and events were unfolding according to His preordained plan, it logically followed that He had sent the heathens, and they were merely His chosen instrument to chastise the English for their sins.”

By the late ninth century the Vikings had destroyed all the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms save Wessex. Alfred restored London in 886 but, as Morris notes, “The devastation brought by the Vikings had taken a particularly heavy toll on the Church. Monasteries had been targeted by raiders from the very first because they were easy prey, undefended and often extremely rich.”

Gold and silver were taken and monks and nuns sold into slavery or held for ransom. A beautiful and treasured gospel book, Codex Aureas, was bought back from the Vikings. They weren’t able to read it, but intuited that it was valuable enough for someone to want to redeem it for cash. It was the Tony Soprano principle — anything someone else valued was worth stealing.

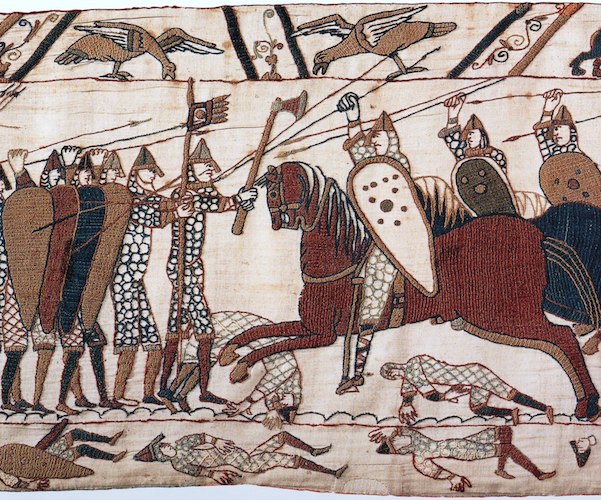

Part of scene 52 of the Bayeux Tapestry. This depicts mounted Normans attacking the Anglo-Saxon infantry. Photo: Wiki Common.

Morris has written an engaging account of turbulent times in a suitable and interesting style. If the book has a shortcoming, it is that the author tends to focus on warfare, siege craft, kingly coups, and the precariousness of daily life. More could have been said, for example, on the evolution of language into the Old English we are familiar with, the manners and customs of both nobility and commoners, and how a concept of “English” came to be communally accepted. This is not to say that the book is scanty or superficial; the nearly one hundred pages of notes, bibliography, and index attest to the scholarly diligence involved in the book’s creation.

Morris notes in his conclusion that two later medieval histories, penned during the 1120-1130 period — William of Malmsbury’s Deeds of the Kings of the English and Henry of Huntington’s History of the English — looked at English history and saw that “the coming of the Normans was simply a new chapter. It was not the end of the story.”

Americans will particularly enjoy this chronicle of the early English Middle Ages because it removes the stereotypical shroud of barbarism that we all too easily use to distance ourselves from the past. Morris’s view of medieval history will be of contemporary service, if only to make us wonder how our country and culture will be viewed 1,500 years hence.

Thomas Filbin is a freelance critic whose work has appeared in the New York Times Book Review, Boston Globe, and Hudson Review.