Book Review: A Valuable Reminder of Lorraine Hansberry’s “Radical Vision”

By Robert Israel

In the process of exploring the ideas that shaped Lorraine Hansberry’s understanding of her art and the world, the volume confirms the writer’s relevance during these troubled but potentially transformative times.

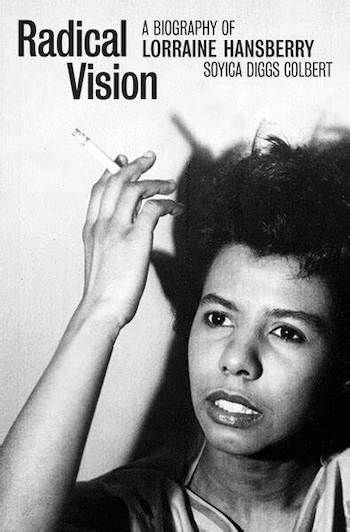

Radical Vision: A Biography of Lorraine Hansberry by Soyica Diggs Colbert. Yale University Press, 288 pages, $35.

In this biography, Soyica Diggs Colbert, a scholar at Georgetown University and author of The African American Theatrical Body and Black Movements: Performance and Cultural Politics, focuses on the intellectual influences that shaped the political and literary consciousness of African American playwright Lorraine Hansberry. She argues that the celebrated writer, who died of cancer at age 35, grappled with two seemingly contradictory energies: a passionate commitment to both activism and to expressing herself as an artist. In the process of exploring the ideas that shaped Hansberry’s understanding of her art and the world, Colbert confirms the relevance of this conflict today. After reading the book, I became convinced that Hansberry, had she survived to her 91st year in 2021, would have been among protesters on 38th and Chicago in Minneapolis on April 20 when word came down that former police officer Derek Chauvin was found guilty of murdering George Floyd. She’d have raised her clenched fist, lowered it, and then made haste to return to her desk to write about it.

In 1959, A Raisin in the Sun was the first play by a Black woman to be produced on Broadway. Hansberry was 29 years old. The production won critical accolades and Tony Awards. But Colbert sets out to prove that Hansberry was far more than a one-hit marvel, a Black writer whose moderate views were palatable for white theater audiences. She was a public intellectual (when that term still meant something), influenced in her 20s by French radical thinkers, such as Simone de Beauvoir and Frantz Fanon, absorbing views rooted in feminism, anticolonialism, existentialism, and Marxism. These, as well as other European influences, were foundational to her critique of American racism, key ingredients in her journalism, short stories, children’s fables, personal and ghostwritten speeches, and political pamphlets.

Hansberry grew up in a politically active household in Chicago and moved to New York City, where she became part of a group of activist writers dedicated to confront entrenched racial inequities. She “spoke on street corners in Harlem,” Colbert notes, and “marched on picket lines.” She was put under surveillance by the FBI. She identified as lesbian, but kept her sexual preference private, marrying — and later divorcing — Robert Nemiroff, a Jewish radical she met on a picket line in New York. (He later served as her literary executor.) Until her illness forced her to retreat to a hospital bed, she remained involved in civil rights and gay liberation movements.

Hansberry developed close alliances with other Black activists, who in turn deeply influenced her work. Singer and political firebrand Nina Simone once described Hansberry as “a girlfriend…. we never talked about men or clothes or other such inconsequential things when we got together. It was always Marx, Lenin and revolution –- real girls’ talk…. Lorraine was most definitely an intellectual and saw civil rights as only one part of the wider racial and class struggle.” Simone would later compose the song “To Be Young, Gifted and Black” inspired by Hansberry’s writings.

During her 20s, Hansberry also worked alongside actor and communist Paul Robeson in Harlem. She became close friends with openly gay author James Baldwin, who, after her death, wrote an essay, “Sweet Lorraine” for Esquire magazine that paid moving homage to their friendship. “We had that respect for each other,” Baldwin wrote, “which perhaps is only felt by people on the same side of the barricades, listening to the accumulating thunder of the hooves of horses and the treads of tanks.”

Author Soyica Diggs Colbert. Photo: Georgetown University.

After Raisin, Hansberry wrote The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window. It received tepid notices. In 2016, Chicago’s Goodman Theatre revived the play. Chicago Tribune theater critic Chris Jones lauded the script as “a masterpiece lost in plain sight.” Why did the script receive such short shrift when it was first produced in New York ? Jones credits the opinions of “white, male critics in New York in 1964 [who] simply could not get their heads around a black woman from Chicago showing such extraordinary range.” In addition, the play was no doubt dismissed because Hansberry’s radicalism was becoming increasingly evident. Fear of white discomfort also explains the sad neglect of the unfinished Les Blancs, which was revived in 2016 (with a final text adapted by Robert Nemiroff) to enormous praise by London’s National Theatre.

Reading Colbert’s book makes one want to return to Hansberry’s unique voice, to read her works more carefully. A failing of Radical Vision is that it does not reprint, at length, more examples of Hansberry’s prose (early in her career she used pseudonyms and these pieces are difficult to find). Colbert quotes from some of these pieces, using them to analyze pivotal points in Hansberry’s life. Having them reprinted in an appendix would have provided valuable context. Another glaring omission: no mention of a key influence in Hansberry’s work, that of Irish playwright Sean O’Casey. Hansberry told the New York Times in 1959 that O’Casey’s work motivated her to capture the “nobility” of everyday people in her work. “It is this dimension of people’s humanity that he imposes on us,” she said. O’Casey, a committed socialist, was best known for plays in which the lower class Irish rose up against their British oppressors (during the 1916 Easter Rising). There is no doubt that this revolutionary spirit, wedded to an interest in economic inequality among the oppressed, influenced Hansberry’s notions of the actions African Americans must take in the United States.

“This story does not end in death,” Colbert writes in her epilogue. She means that Hansberry’s work lives on because her humanity and compelling articulation of our troubled history with regards to race is a vital resource during these troubled but potentially transformative times. The work of Baldwin is enjoying a well-deserved revival today. Colbert’s illuminating study suggests that a Hansberry revival would be just as welcome.

Robert Israel, an Arts Fuse contributor since 2013, can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.

Tagged: Lorraine Hansberry, Radical Vision: A Biography of Lorraine Hansberry, Robert Isreal

Great piece, Robert. I’ve taught Raisin pretty much every semester for the past few years, so I’ve read the thing at least a dozen times and it’s still fresh, incisive, timely, and relatable. My favorite moments as a teacher are when one of my students says “I’m Beneatha” or “I’m Walter.” Then we talk about what that means and what to make of it.

I agree with the critics who panned Sidney Brustein’s Window. But maybe I’ll give it another look.

Is there any description of the meeting Baldwin set up between some of his literary and intellectual friends and RFK? That’s a moment in history it would be fascinating to hear more about.

Matt: Thanks for your comment. There are a few reports about what is now called the Baldwin-Kennedy meeting that you can find online and in the Colbert book. Hansberry reportedly stormed out of the meeting, fed up with the liberal claptrap she heard. Her words did reach JFK, however, when he said, reportedly the next day, that the US had a “moral” obligation to work toward civil rights.