Book Review: John Edgar Wideman — Masterful Stories that Bear the Weight of Reality

By Robert Israel

A singular muscularity infuses these short stories, a confidence that astonishes.

You Made Me Love You: Selected Stories, 1981-2018, by John Edgar Wideman. Scribner, New York, 462 pages, $30

Compiled over a 37-year span, this selection of short stories by John Edgar Wideman, who will soon turn 80, introduces the reader to characters who face peril, pathos, and heartache. A singular muscularity infuses these narratives, a confidence that astonishes.

Many of the pieces in this volume are short. Wideman groups them under the label “Briefs,” and they are difficult to categorize. They are not quite “short shorts” because they do not provide truncated beginnings, middles, and ends. They do not fall into the category of “flash fiction” either, a literary genre that American author Diane Williams excels at, bursts that conform to a designated character count on a computer screen. Neither are they prose poems: Wideman does not often draw on rhythmic or musical cadences. At their best, these are microbursts of experience that take readers on journeys that jump forward and backward in time to places that we haven’t been to before but think we recognize. Until Wideman asserts their violent strangeness.

The African-American neighborhood of Homewood, in Pittsburgh, is one of these destinations. Wideman was born here, in 1941, predating, by four years, playwright August Wilson, who grew up in the city’s Hill District. He quit that neighborhood after high school, bound for UPenn, thanks to an academic scholarship. Wilson, who dropped out of high school at age 15, took a bit longer to exit the Steel City, relocating to St. Paul as an adult, where he discovered his métier as a dramatist, eventually winning a pair of Pulitzer Prizes. Wilson wrote about the important lessons he learned in the Hill District, many of them violent (he witnessed a murder), all of them transformational. Wideman is less generous and unforgiving about the neighborhood’s urban blight. One story sums up his anything-but-nostalgic attitude: “Somebody should make a deep ditch out of Homewood Avenue and…push the rowhouses and boarded storefronts into the hole. Bury it all.”

But Wideman — who returns to Homewood as settings for several of his stores — does not succeed in burying his old neighborhood. Ironically, when he writes about other cities — New York, Paris, Cape Town — Homewood travels with him.

In the short short story “Witness,” a handicapped resident views a horrific event on Frankstown Road in Homewood. From a perch on a sixth-floor fire escape, the man observes a 15-year-old boy being shot and killed. The adolescent’s relatives arrive to inspect the spot where the murder took place. The narrator shares their grief from a distance. “Forgive me, Jesus,” he concludes, “but look like they grief dancing, like the sidewalk too cold or too hot they had to jump around not to burn up.”

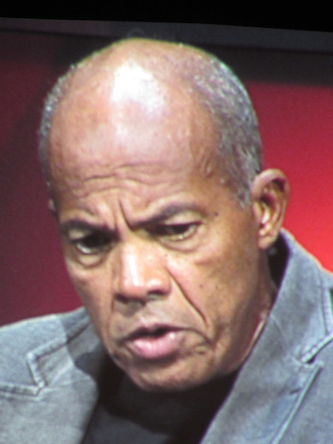

John Edgar Wideman at the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards in 2010. Photo: Wiki Common.

The violent peril that lurks night and day in Homewood also drives the story “Manhole,” which is set along a jogging path that abuts New York’s East River. The narrator imagines (is he really imagining?) being pursued by racists: “…then the unmistakable pop which takes me down sprawling on the asphalt, hitting hard as if I’d been pushed from a speeding drive-by, but I’m not dead I’m rolling, rolling fast to my feet, haul-assing like a turkey through the corn for cover round a bend as if a bullet couldn’t catch me if it wanted to.” The narrator lives out the fears that are regularly felt by African Americans in the heart of the urban danger zone. Reality is blurred; adrenaline courses through his veins. Wideman puts us there, running alongside him, bedeviled by the same questions. What’s happening? Will I survive?

One of the book’s most vividly told tales is a multilayered piece titled “Weight,” narrated by a writer who shares a draft of a story with his mother in an attempt to bring her closer to how he is living as an adult. His mother deeply disapproves of what she reads, anxious for his future. “I ought to know,” Wideman writes, “since I’m one of the burdens bowing her shoulders. She loves heavy, hopeless me unconditionally. Before I was born, Mom loved me, forever and ever till death do us part. I’ll never be anyone else’s darling, darling boy, so it’s her fault, her doing, isn’t it, that neither of us can face the thought of losing the other.” Wideman peels back the layers of the mother and son’s burdensome personal history, exploring how the tension between them tightens and suffocates. There are no intimations of resolution beyond the confrontation of the immediate. There might be a future for this relationship; it might also deteriorate further. It might bear the weight of reality.

Wideman’s poignant examination of his characters’ tangled knots of passion suggests why he called the book You Made Me Love You, which is the title of a song popularized by crooner Al Jolson in 1913 and later immortalized by a puppy love-crushed Judy Garland in 1937 when she sang it to a photo of her matinee idol Clark Gable. The characters in this remarkable collection exist for each other day by day — until they don’t. They are doomed to be consanguineous, fated to love one another — it is blood knot as yin and yang, a sinewy tether to a love/death grip.

Robert Israel, an Arts Fuse contributor since 2013, can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.